Kojiki: The Foundation of Japanese Mythology and Shinto Beliefs

Imagine opening a book that begins with the birth of the universe, the creation of islands, and the arrival of gods who shape a nation’s destiny.

This is the Kojiki (古事記) — Japan’s oldest chronicle, compiled in the early 8th century. Far more than a record of the past, it weaves together mythology, history, and spirituality, revealing how the Japanese people understood their origins and place in the world.

From dramatic tales of gods like Amaterasu, the radiant sun goddess, to epic legends of heroes like Yamato Takeru, the Kojiki is a treasure trove of stories that still influence Japan’s culture, festivals, and identity today.

In this article, let us explore why the Kojiki remains not only a historical document, but also a timeless gateway into the heart of Japanese tradition.

What is the Kojiki?

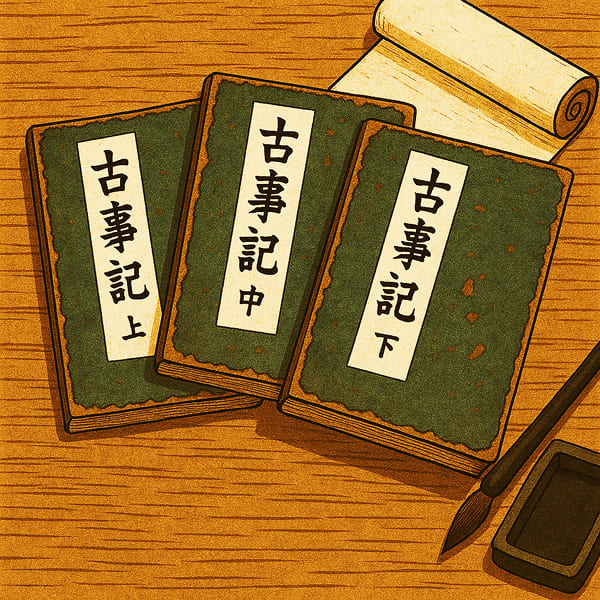

The Kojiki, literally “Records of Ancient Matters,” is Japan’s oldest surviving book, compiled in 712 CE by Ō no Yasumaro (太安万侶) and presented to Empress Genmei (元明天皇). It is covering events from the creation of heaven and earth to the reign of Empress Suiko in the 7th century. Rather than being a simple chronicle, the Kojiki blends history with mythology, legends, and songs.

Key Features of the Kojiki

- Three-part structure: upper, middle, and lower volumes

- Mythological origins: from the birth of the gods to early emperors

- Izumo myths: strong focus on tales of Ōkuninushi and regional traditions

- Ancient songs (kayō): foundations of later waka poetry

- Manuscript tradition: the original is lost, but handwritten copies remain

- Cultural emphasis: more literary and folk-centered than the Nihon Shoki

Because of these qualities, the Kojiki is not only a record of divine origins and imperial legitimacy, but also a cultural treasure that continues to inspire literature, art, and modern popular culture.

Origins and Purpose of the Kojiki

The Kojiki was born out of both necessity and vision during the Nara period (710–794 CE). Earlier historical records, such as the Tennōki (天皇記) and Kokki (国記), were said to have been destroyed in a fire during the Isshi Incident (645 CE), when the powerful Soga clan fell from power. As a result, much of Japan’s early history and imperial genealogy risked being lost.

By the late 7th century, oral traditions and family records were still being passed down, but they had become mixed with uncertainty and exaggeration. To preserve them, Emperor Tenmu ordered the court scholar Hieda no Are, renowned for his memory, to memorize and recite these traditions. Decades later, under Empress Genmei, the court official Ō no Yasumaro compiled Are’s recitations into a written text, completing the Kojiki in 712 CE.

Why the Kojiki Was Compiled

- Recovering lost history: to replace the burned chronicles and safeguard Japan’s origins.

- Imperial legitimacy: to link the imperial line directly to the gods, reinforcing its divine authority.

- Preservation of oral traditions: ensuring that myths, genealogies, and songs would not vanish.

- Nation-building: providing a unifying story of Japan’s beginnings during an era of political centralization.

In this way, the Kojiki was not only a cultural project, but also a response to loss—an attempt to restore what had been destroyed and to secure Japan’s spiritual and political identity for the future.

Stories within the Kojiki

The Kojiki is more than a chronicle—it is a vast collection of creation myths, divine conflicts, heroic adventures, and imperial genealogies that explain how Japan and its people came to be.

These stories begin with the deeds of gods (kami) and legendary figures, then flow seamlessly into the lineage of emperors, portraying the Japanese imperial line as a direct continuation of the divine world.

Creation Myths

- Izanagi and Izanami: the divine couple who created the Japanese islands, giving birth to both gods and natural phenomena. Their tragic separation after Izanami’s death echoes creation-and-loss motifs found in world mythology.

- The Three Divine Siblings: from Izanagi’s purification ritual were born Amaterasu (sun goddess), Susanoo (storm god), and Tsukuyomi (moon god), deities central to Shinto belief.

A small break — a little side note

Experience the Kojiki as it was written.

This video presents the original classical text side-by-side with a modern translation and historical commentary, revealing both what the myth says and how it’s interpreted today.

Focusing on Izanagi and Izanami’s creation of the Japanese islands, and complete with English subtitles, it’s an engaging gateway into the language, myth, and legacy of Japan’s oldest chronicle.

Divine and Heroic Tales

- Susanoo and the Eight-Headed Serpent (Yamata no Orochi): a dramatic myth of chaos, bravery, and the origin of sacred objects such as the sword Kusanagi.

- Ōkuninushi and the Transfer of the Land (Kuni-yuzuri): the tale of a god who ruled the earthly realm before yielding it to the descendants of the sun goddess, linking regional myths (notably from Izumo) with imperial authority.

- Prince Yamato Takeru: a warrior-hero whose epic journeys and tragic fate blend myth with early history, leaving place names and traditions throughout Japan.

Imperial Genealogy

The Kojiki does not stop with myths of the gods.

After the Upper Volume, which records the age of the deities, the narrative shifts in the Middle and Lower Volumes to the human world—tracing the imperial line from Emperor Jimmu down to Empress Suiko in the 7th century.

This seamless transition from myth to dynasty sets the stage for the Kojiki’s unique role, explored in more detail in the next section.

In this way, the Kojiki shares similarities with Greek and Norse mythology in providing a cultural foundation of identity and values.

However, it is also unique: the myths of the gods do not stand apart as separate tales, but flow directly into the imperial genealogy, linking the divine world to the human realm.

This connection between myth and living history makes the Kojiki unlike most other world mythologies—a sacred text that continues to shape Japan’s sense of identity even today.

Kojiki and the Imperial Line

As seen in the transition from the myths of the gods to the stories of emperors, the Kojiki goes beyond mythology to establish a sacred genealogy of the Japanese imperial line.

The narrative begins with the sun goddess Amaterasu, whose descendant Ninigi-no-Mikoto descended from heaven in the Tenson Kōrin. From his lineage came Emperor Jimmu, regarded as Japan’s first emperor, who led the eastern expedition and laid the foundations of the imperial dynasty.

Myth Becomes History

In the Kojiki, myth was not just preserved—it became history.

By weaving the story of the gods directly into the lineage of emperors, the text gave Japan:

- A sacred origin

- An unbroken line

- A living symbol of continuity

This is why the imperial line remains more than political—it is, at its core, a myth made real.

Cultural Legacy and Influence Today

The Kojiki is not just a relic of the past—it continues to shape Japanese culture and identity in ways both sacred and everyday. Its myths live on in rituals, traditions, and even in the stories told in popular media.

Shrines and Sacred Sites

Many of Japan’s most important shrines are directly linked to Kojiki myths.

-

Ise Grand Shrine (Ise Jingū) honors the sun goddess Amaterasu, the supreme deity of the text.

-

Izumo Taisha is dedicated to Ōkuninushi, the god of nation-building and marriage, whose story of kuni-yuzuri (transfer of the land) is central to the Kojiki.

Visiting these shrines is not only a spiritual experience but also a way of stepping into the living world of ancient mythology.

Festivals and Traditions

Seasonal festivals and rituals often echo Kojiki tales in ways that remain visible today.

-

At Ise Grand Shrine, dedicated to Amaterasu, sacred ceremonies include rituals that symbolically recall the goddess’s retreat into the cave and her return, representing the cycle of darkness and light.

-

In Iwami Kagura (a dynamic form of sacred dance in Shimane Prefecture), the dramatic battle between Susanoo and the serpent Yamata no Orochi is performed with giant serpent costumes, bringing one of the Kojiki’s most famous myths to life before modern audiences.

Through these performances, mythology blends with community life, ensuring that the ancient stories remain part of Japan’s cultural memory.

Literature and Popular Culture

Far from fading into obscurity, Kojiki’s gods and heroes have found new life in modern storytelling:

- Classical works of waka poetry and Noh theater drew heavily on its myths.

- Today, its deities appear in manga, anime, video games, and even novels, where figures like Amaterasu and Susanoo are reimagined for new audiences.

Through shrines, festivals, and creative works, the Kojiki continues to bridge ancient tradition and modern imagination—a testament to its enduring role in Japanese culture.

Comparison with the Nihon Shoki

Alongside the Kojiki, the Nihon Shoki (日本書紀, “Chronicles of Japan”), compiled in 720 CE, forms the other great foundation of Japan’s early history. While the two texts often overlap in content, they were created with different purposes in mind:

- Kojiki: compiled in 712 CE, written in a more literary style, focused on preserving myths, songs, and oral traditions for a domestic audience.

- Nihon Shoki: compiled in 720 CE, modeled after Chinese dynastic histories, intended as an official chronicle for diplomacy and state legitimacy.

Because of these differences, the two works sometimes record different versions of the same myth or place emphasis on different details.

Together, however, they complement each other: the Kojiki preserves the voice of ancient tradition, while the Nihon Shoki provides a formal, political narrative of Japan’s past.

Why the Kojiki Still Matters

The Kojiki is far more than an ancient chronicle—it remains a living foundation of Japanese identity and culture.

Its stories remind people that humans, nature, and the divine are deeply connected, offering a worldview where mountains, rivers, and even the sun itself are seen as part of a sacred order.

For the Japanese

For the Japanese, the Kojiki provides a sense of roots and continuity.

Even if most people only encounter the name “Kojiki” in school textbooks, the traditions it preserves live on in daily life:

- Shrines and Shinto rituals that trace back to its myths

- Festivals and local customs shaped by the stories of gods and heroes

- The imperial family presented as a continuation of the divine line

In this way, the Kojiki is not something people study every day, yet it quietly informs how they experience the world—whether through a seasonal festival, a shrine visit, or the presence of the imperial family in national life.

For Readers Abroad

For readers abroad, the Kojiki is more than mythology—it is an entry point into the roots of Japanese culture, a way to understand the values, symbols, and imagination that still resonate in Japan today.

By exploring the Kojiki, one does not just learn about myths of the past, but gains insight into the spirit of a nation that continues to cherish its connection between nature, people, and the divine.

In this sense, the Kojiki can serve as a guidebook for understanding Japan itself—not only its ancient traditions, but also the foundations of its modern culture and national character.

Ironically, because many Japanese people rarely engage with the Kojiki beyond a mention in history class, those who approach it from outside may gain an even deeper appreciation of Japan’s cultural roots than many within the country. To read the Kojiki is to glimpse the soul of Japan.

Conclusion: A Timeless Gateway to Japan

The Kojiki is not simply a book of myths, nor merely a record of emperors—it is the bridge that unites gods, people, and history.

By preserving creation stories, heroic legends, and the imperial lineage, it gave Japan both a sacred past and a cultural foundation that still shapes identity today.

For the Japanese, its presence is often subtle—hidden in shrines, festivals, and traditions that quietly echo the ancient tales.

For readers abroad, it opens a window into the roots of Japan, offering a way to understand the values and imagination that continue to guide the nation.

In the end, to explore the Kojiki is to glimpse the living soul of Japan—a story that began in the age of the gods and still flows through the present.