Susanoo-no-Mikoto: The Storm God Who Learned to Grow

.jpg)

Have you ever heard of a god who is both a troublemaker and a hero?

In Japanese mythology, that god is Susanoo-no-Mikoto, the storm god who rules over the sea, the wind, and raging tempests.

Susanoo is well known for his fierce temper and reckless behavior, yet he is also remembered as a heroic figure — one who showed great courage and strength.

Beyond this, he holds an unexpected place in Japanese culture — as the god who composed Japan’s very first waka poem.

Why was Susanoo so fierce and difficult to control?

And what kind of feelings did he pour into the waka poem he composed?

This is a story of growth — of an unfinished god who, through experience and hardship, gradually came to possess the heart, sensitivity, and responsibility of a true deity.

Let us set out together on a journey to learn more about Susanoo.

By following his transformation, we can explore why this storm god continues to captivate people’s hearts even today.

Who Is Susanoo-no-Mikoto?

So who exactly is Susanoo-no-Mikoto?

Before exploring his myths and the path of his growth, let us first look at his place within the divine family of Japanese mythology.

Profile of Susanoo-no-Mikoto

-

Parent

Born from the nose of the creator god Izanagi-no-Mikoto during his sacred purification ritual. -

Siblings

Brother of Amaterasu-Ōmikami, the Sun Goddess, and Tsukuyomi-no-Mikoto, the Moon God. Together, they are known as the Three Precious Children (Mihashira-no-Uzunomiko). -

Wife

Kushinada-hime, the maiden he saved from Yamata-no-Orochi. -

Children and Lineage

Through his descendants comes Ōkuninushi-no-Mikoto, a central god of Izumo mythology. -

Role in the Imperial Line

Considered part of the divine lineage connected to Japan’s imperial mythology. -

Another Name

Later worshipped as Gozu Tennō (牛頭天王), a guardian deity believed to protect against disease and calamity.

The Meaning Behind His Name

The name Susanoo carries several layers of meaning, reflecting the many sides of his character.

| Interpretation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| To rage, to storm | Emphasizes his identity as a god of violent winds and tempests |

| To push forward | Suggests unstoppable energy and impulsive movement |

| Place-name origin (Susa, Izumo) | Hints at his roots as a local deity later elevated to national importance |

Together, these meanings paint Susanoo as a god of powerful motion— a force that destroys, yet also clears the way for renewal.

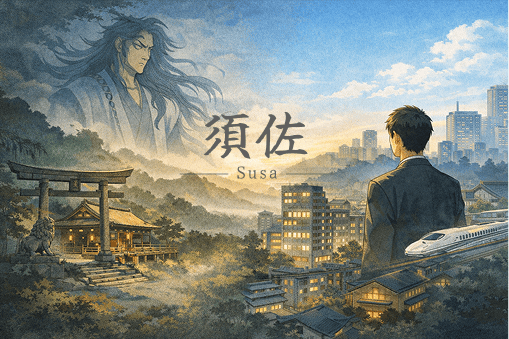

A small break — a little side note

The Susa Name That Still Lives On

In modern Japan, there are people who carry the family name Susa (須佐). It is a rare surname, and even as a Japanese, I only became aware of it recently after seeing someone with that name appear on a news program.

Interestingly, this surname does not appear to come directly from Susanoo himself.

However, it is closely connected to Susa, an ancient place name in Izumo — the very region deeply associated with Susanoo’s myths.

The fact that the name Susa has survived for centuries not only as a place name or shrine name, but also as a family name, is quietly fascinating.

It suggests that memories of myth still live on — not loudly, but gently — woven into everyday life.

How Susanoo Is Remembered Today

Although ancient myths often highlight his wild behavior, Susanoo is also deeply respected in Japanese belief.

- In Izumo, he is honored as the heroic serpent-slayer and ancestor of important local gods.

- In Shinto worship, he is associated not only with storms and the sea, but also with fertility, creativity, and protection.

- As Gozu Tennō, he became a guardian against epidemics, most famously worshipped at Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto, the heart of the Gion Festival.

Because of these many roles, Susanoo remains one of the most approachable and human-like gods in Japanese mythology.

Mythological Episodes: Chaos and Meaning

Susanoo is often remembered as a wild and destructive god, especially in the stories that describe his conflict with Amaterasu.

Yet this image comes from an early period in his myth, before he had learned to control his strength or emotions.

In this section, we will take a closer look at this early image of Susanoo, and consider what it may represent.

Susanoo and His Conflict with Amaterasu

Let us first take a brief look at the story of the conflict between Susanoo and Amaterasu.

Susanoo visited the heavenly realm ruled by his elder sister, the Sun Goddess Amaterasu.

At first, he claimed that his intentions were peaceful.

However, his actions soon turned destructive and extreme.

Susanoo trampled Amaterasu’s rice fields, destroyed sacred buildings, and finally committed the most shocking act of all — throwing a flayed horse into her weaving hall, a place that symbolized ritual purity and cosmic order.

These actions deeply unsettled Amaterasu.

In response, she withdrew into a cave, and the world was plunged into darkness.

These events established Susanoo’s image as a dangerous and uncontrollable god, feared for the power he could not yet restrain.

The Storm God as a Symbol of Uncontrolled Power

This episode takes place not long after Susanoo’s birth, during an early stage of his life as a god.

Traditionally, Susanoo’s actions in this story have been understood as symbolic expressions of storms — forces that damage crops and threaten human life.

For ancient agricultural societies, storms were a source of deep fear.

By portraying Susanoo as a god who tramples rice fields and destroys places essential to human survival, the myth gives shape to the terror of violent natural power.

But what do we see when we focus on Susanoo himself?

This episode also reveals his immaturity.

Although he possessed immense strength, he had not yet learned how to control it.

Driven by emotions he could not restrain, his actions became reckless and excessive.

Seen from this perspective, Susanoo is portrayed not simply as a force of destruction, but as an unfinished god — one still struggling to master his own power.

A Later Perspective: Forest and Field

When we view Susanoo’s story as a whole, another perspective begins to emerge.

After the events of his conflict with Amaterasu, Susanoo goes on to defeat Yamata-no-Orochi, marry Kushinada-hime, and grow into a fully matured and responsible god.

In later myths, he reveals yet another side of himself — one far removed from the image of a reckless destroyer.

Susanoo is said to create trees such as cedar and cypress from his own hair, spreading forests across the land.

He teaches people how to use these trees to build houses, ships, and tools.

Here, he appears not as a force of chaos, but as a guardian of forests and natural resources.

Seen from this later stage of his life, the earlier conflict with Amaterasu can be reconsidered in a new light.

Amaterasu embodies rice cultivation, agriculture, and human order.

Susanoo’s uncontrolled actions, in contrast, may be read as reflecting tension with the unchecked expansion of cultivated land and the loss of the forests that once covered it.

This interpretation does not replace the traditional understanding of the myth.

Rather, it adds another layer — one that becomes visible only when Susanoo’s story is viewed from beginning to end.

Note:

At the time of this conflict, Susanoo was still an immature deity.

This perspective does not imply conscious intent, but offers a way to reflect on how his later role may cast new light on earlier myths.

Chaos as the Beginning of Growth

In these early myths, we have considered Susanoo’s actions from two different perspectives.

How do these stories change the way you see his violent behavior?

Perhaps Susanoo was not merely a troublemaker.

He may have been an unfinished god, caught between overwhelming power and a responsibility too great for him to bear at that stage of his life.

Seen this way, his chaos reflects not malice, but the beginning of a long journey toward growth.

Susanoo and Poetry: An Unexpected Side of the Storm God

Susanoo is known for his wild and uncontrollable nature, but he also possesses a far less familiar side.

He is said to have composed the very first waka, Japan’s classical form of poetry, and is often called the father of Japanese waka.

How did such a fierce and reckless storm god come to write poetry?

Let us take a closer look.

The First Waka and a Moment of Peace

After marrying Kushinada-hime, Susanoo built a home where he could live and protect his family.

It was at this moment — not in conflict or rage — that he composed his famous poem.

八雲立つ 出雲八重垣 妻ごみに 八重垣つくる その八重垣を

Yakumo tatsu Izumo yaegaki tsuma-gomi ni / yaegaki tsukuru sono yaegaki o

Rising clouds over Izumo appear like many-layered fences;

so too I will build layered fences to protect my beloved wife.

This waka, recorded in the Kojiki, is considered the oldest waka in Japanese history.

Its imagery is gentle and filled with affection, far removed from the violent scenes of Susanoo’s earlier myths.

Poetry as a Sign of Growth

Here, Susanoo appears strikingly different from his youthful, reckless self.

The overwhelming power that once burst forth through uncontrolled emotion is now guided by care, love, and responsibility.

His strength is no longer destructive — it is directed toward protection and creation.

This poem can be seen as a quiet declaration of Susanoo’s growth.

Through waka, he expresses the heart of a god who has learned that true strength lies not in overwhelming others, but in protecting what is precious.

Susanoo’s story is often told as a heroic tale, but it is also a story of inner transformation.

Through struggle and hardship, an unfinished god learned to carry responsibility and grew into the vessel of a true deity.

His waka stands as a gentle yet powerful testament to that journey.

Shrines and Festivals of Susanoo

Even today, there are places in Japan where you can still feel the presence of Susanoo — the brave hero of myth and legend.

Let’s take a look at some of the most famous shrines and festivals dedicated to him.

Izumo: The Land of His Legends

Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) is the stage for many of Susanoo’s most famous myths. Even today, you can visit shrines here where his presence still feels close.

-

Susa Shrine (須佐神社)

Known as the only shrine in Japan said to enshrine the very spirit of Susanoo.

Behind its main hall stands a majestic 1,300-year-old cedar tree, radiating power and presence like the guardian of the land itself.The shrine is also associated with blessings for marriage, family prosperity, household safety, and protection from misfortune.

A sacred spring called Shio-no-i, where Susanoo is believed to have purified the land himself, can still be seen today.For those who would like to learn more, you may also find the following official site helpful.

Official introduction (Izumo Tourism) -

Yaegaki Shrine (八重垣神社)

Dedicated to both Susanoo and his wife Kushinada-hime, this shrine is tied to the legend of the serpent.

It is home to the Mirror Pond (Kagami-no-ike), where Kushinada-hime is said to have once hidden, gazing at her reflection in the water.Today, the pond is famous for its love fortune ritual, where visitors place a coin on paper and watch it float to divine the future of their relationships.

The shrine also features the Couple Camellia (Renri Tsubaki)—two trees joined as one, a living symbol of eternal love.If you would like to explore further details about this shrine, the official site below offers more information.

Official introduction (Shimane Tourism)

Together, these shrines show how Susanoo is remembered not only as a storm god and serpent-slayer, but also as a guardian of families, love, and community.

A small break — a little side note

Have you ever wondered what Susa Shrine, the sacred place dedicated to Susanoo-no-Mikoto, is like?

In this video, let us take a slow and peaceful walk through its grounds.

Surrounded by ancient trees and deep silence, the shrine radiates a calm and dignified beauty, as if time itself has chosen to linger here.

The quiet approach, the wind passing softly through the forest, and the towering cedar behind the main hall create a feeling of quiet clarity — as though your heart is being gently cleansed.

Even today, you may sense the presence of Susanoo, still watching over this land in silence.

Kyoto: Yasaka Shrine and the Gion Festival

As Susanoo’s worship spread beyond Izumo, his role continued to evolve.

In Kyoto, the same deity came to be revered under another name — Gozu Tennō.

The most famous place of worship is Yasaka Shrine in Kyoto, the head shrine of thousands of Yasaka shrines across Japan.

Affectionately known as “Gion-san,” the shrine is beloved by locals and visitors alike.

Every July, Yasaka Shrine hosts the Gion Festival, counted among Japan’s three great festivals. It began as a ritual to appease Susanoo (as Gozu Tennō) and pray for protection from disease and disaster.

The shrine itself is also famous for its striking vermillion West Tower Gate, a favorite photo spot for travelers.

Visitors pray here for blessings such as protection from misfortune, good relationships, and beauty.

If you would like to explore further details about Yasaka Shrine and the Gion Festival, the official site below offers more information.

Official introduction (Kyoto Travel)

Through these shrines and festivals, Susanoo lives on — not just as a storm god of ancient myth, but as a guardian woven into the daily lives and traditions of Japanese people.

Susanoo’s Legacy: A Universal Story of Growth

Susanoo’s story offers more than a legacy of worship.

It carries a message that reaches far beyond Japan — a message about how we grow, struggle, and learn to carry responsibility.

Let us take a closer look at what his story continues to teach us today.

An Unfinished God Who Learned to Grow

Susanoo’s story is one of growth — not sudden redemption, but gradual maturation.

Unlike gods who are born complete and composed, Susanoo enters the world as an unfinished being.

He possesses overwhelming power, yet lacks the ability to control his emotions or fully understand the responsibility that comes with such strength.

As a result, he causes harm, angers others, and at times becomes a figure of fear.

But these failures are not meaningless.

Through exile, hardship, and relationships with others, Susanoo slowly learns what it means to hold power without being consumed by it.

Step by step, he grows strong enough to bear its weight.

His story shows that growth is not about perfection, but about learning through mistakes and facing our own limitations.

Strength Guided by Responsibility

In this way, Susanoo’s journey closely mirrors the human experience.

Strength, talent, or authority alone are not what define maturity.

What matters is how they are used — whether they lead to care, protection, and shared well-being.

Power must be guided by consideration for others.

Emotion must be tempered by reflection.

Authority must be accompanied by humility.

Susanoo’s transformation — from a god who throws the world into chaos to one who protects family, community, and society — reflects a universal truth:

true strength is found not in domination, but in responsibility.

That his story contains both destruction and poetry, both storm and shelter, is no coincidence.

Why Susanoo Still Speaks to Us

In modern life, many people struggle with emotions, pressure, and responsibilities that feel too heavy to carry.

Susanoo’s story speaks directly to this experience.

Growth does not begin with perfection, but with the courage to face our own immaturity and to choose how we will change.

Susanoo continues to resonate with people across cultures not because he was perfect, but because he learned how to transform raw power into care, protection, and purpose.

In this sense, his story is not only a Japanese myth, but a quiet reflection of the human journey itself.

Conclusion: The Enduring Meaning of Susanoo

Susanoo-no-Mikoto is a god of many faces — a storm that brings destruction, a hero who protects the land, and a poet who sings of love and shelter.

At first glance, his story may seem chaotic.

Yet when viewed as a whole, it reveals something deeply human:

a journey from immaturity to responsibility, from uncontrolled power to strength guided by care.

Susanoo is not remembered because he was flawless.

He is remembered because he changed.

Through failure, exile, struggle, and connection with others, he learned how to carry his power without being consumed by it.

This is why Susanoo continues to resonate across time and culture.

His myth suggests that growth is not about being born complete, but about learning how to live with what we are given — and choosing, again and again, how to shape it.

In the end, Susanoo is not only a god of storms, but a symbol of transformation.

And perhaps that is why his story still speaks to us today, quietly asking how we, too, will grow.