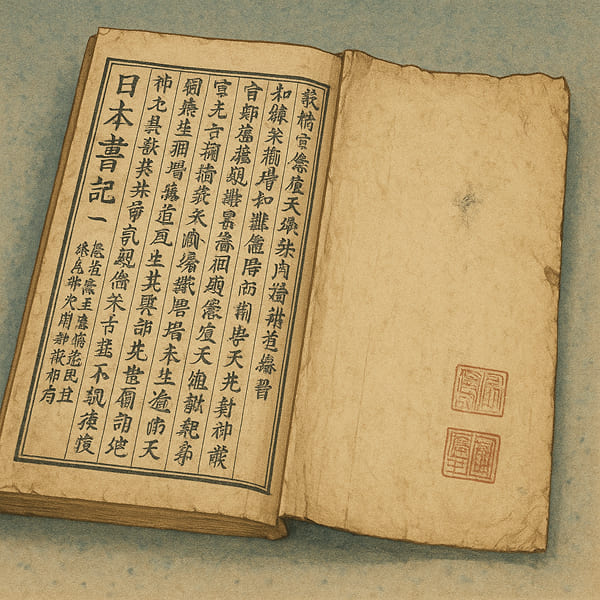

Nihon Shoki: Japan's Official Chronicle of Myth and History

A nation born from the union of gods, and a history written to shape its destiny.

The Nihon Shoki—compiled in 720 CE—is one of Japan’s oldest chronicles, blending myths of creation with the records of emperors and early diplomacy. More than just a book, it was crafted to establish legitimacy, preserve tradition, and connect Japan with the broader world.

In this article, we will explore its mythological tales, historical accounts, cultural purpose, and lasting influence on Japan’s identity.

What is the Nihon Shoki?

The Nihon Shoki (日本書紀), also known as the Chronicles of Japan, is one of Japan’s oldest official histories, completed in 720 CE under the order of the imperial court. It spans 30 volumes, covering the mythical origins of Japan through the reign of Empress Jitō.

Structure and Content

- Volumes 1–2: The mythological age, describing the creation of the world and the deeds of gods.

- Volumes 3–30: The genealogies and achievements of emperors, as well as foreign relations, natural phenomena, and political events.

- Includes 128 waka poems, reflecting the deep connection between poetry, politics, and court life.

Style and Language

The Nihon Shoki was compiled by multiple editors and scholars, which led to some variations in style and structure.

It was written in classical Chinese, the scholarly language of East Asia, but certain passages contain annotations (kunten) instructing how to read them in Japanese. This gives the text a unique form known as wakakanbun (和化漢文)—a blend of Chinese formality and Japanese expression.

Purpose and Background

The chronicle itself does not explicitly state why it was compiled. However, historians believe it was created to:

- Establish the legitimacy of the imperial line

- Present Japan as a civilized nation equal to Tang China and Silla Korea

- Provide a written foundation of identity for both domestic and international audiences

In short, the Nihon Shoki is not only a record of myths and history, but also a political and cultural statement that shaped Japan’s place in the world.

The World of Myth: Gods, Creation, and Legends

The opening volumes of the Nihon Shoki are filled with myths that explain how Japan itself was created and how divine authority became tied to the imperial family. These stories are not only imaginative tales but also serve as the foundation of Shinto belief and imperial legitimacy.

The Birth of the Land: Izanagi and Izanami

The chronicle begins with the divine couple Izanagi and Izanami, who stirred the sea with a jeweled spear and created the islands of Japan. Their union gave rise to countless gods, natural forces, and even the cycles of life and death. This myth places the Japanese islands at the center of a sacred creation.

A small break — a little side note

This short video illustrates the kuniumi myth from the Nihon Shoki, where the divine couple Izanagi and Izanami stir the sea with a jeweled spear to create the islands of Japan—a vivid glimpse of how ancient chronicles imagined the nation’s very beginning.

Light and Storm: Amaterasu and Susanoo

Among their descendants were the sun goddess Amaterasu and her stormy brother Susanoo. Their rivalry and eventual reconciliation symbolize the balance of order and chaos, light and darkness.

Amaterasu, revered as the ancestor of the imperial line, embodies authority and harmony, while Susanoo represents untamed nature and human flaws.

Descent from Heaven: Ninigi no Mikoto

One of the most important episodes is the Tenson Kōrin, the descent of Ninigi no Mikoto, Amaterasu’s grandson, from the heavens to rule the earth. This myth directly links the gods to the emperors of Japan, presenting the imperial family as divine descendants.

From Myth to Faith and Rule

These stories were not preserved as mere folklore. They provided a spiritual foundation for Shinto rituals and justified the imperial family’s authority as divinely ordained. In this way, the Nihon Shoki’s myths shaped both religion and politics in Japan for centuries.

Historical Chronicle: From Emperors to Events

After the mythological age, the Nihon Shoki transitions into a record of emperors, dynasties, and political events, creating one of the earliest continuous chronicles of Japan’s history.

The First Emperor: Jimmu

The narrative introduces Emperor Jimmu, regarded as the first emperor of Japan and a direct descendant of the gods. His legendary eastern expedition—moving from Kyushu toward the Yamato region (present-day Nara)—established the imperial line and created Japan’s first political center in Yamato.

Although historians debate the historicity of Jimmu, his story symbolizes the link between myth and monarchy.

A Dynasty-Centered Record

From Jimmu onward, the chronicle focuses on the imperial genealogy and the deeds of successive rulers. Each emperor’s reign is presented as part of an unbroken lineage, emphasizing the continuity and legitimacy of imperial authority.

One notable example is Empress Suiko (r. 593–628), Japan’s first recorded female ruler. Under her reign, with the guidance of her regent Prince Shōtoku, Buddhism was officially promoted, the Seventeen-Article Constitution was proclaimed, and embassies were sent to China’s Sui dynasty. These accounts highlight how the imperial court not only preserved its lineage but also actively shaped Japan’s political, cultural, and international identity.

Encounters Beyond Japan

The Nihon Shoki also documents diplomatic exchanges with neighboring states such as China’s Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) and Korea’s Silla kingdom (57 BCE–935 CE). These records reveal Japan’s growing awareness of its place in East Asia, showing both cultural borrowing—such as Buddhism, writing systems, and government models—and political ambition to stand alongside these powerful states.

In this way, the Nihon Shoki bridges the world of myth and legend with the realm of recorded history, presenting Japan as a nation with both divine origins and historical continuity.

Comparison: Kojiki vs. Nihon Shoki

The Nihon Shoki is often compared with the Kojiki (古事記), another early chronicle completed just a few years earlier in 712 CE. At first glance they may seem similar, but their purposes and styles differ in important ways.

Key Differences at a Glance

| Feature | Kojiki (古事記) – 712 CE | Nihon Shoki (日本書紀) – 720 CE |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Mythology, folklore, sacred origins | Imperial genealogy, political events, foreign relations |

| Style | Narrative, poetic, story-like | Annalistic, year-by-year chronicle |

| Language | Mix of Chinese characters and Japanese readings (man’yōgana) | Classical Chinese (for international prestige) |

| Purpose | Preserve native myths and oral traditions | Establish imperial legitimacy and serve as diplomatic text |

| Audience | Primarily domestic (court and cultural identity) | Domestic + international (neighboring states like Tang and Silla) |

Two Texts, One Identity

While the Kojiki highlights Japan’s mythic imagination and cultural roots, the Nihon Shoki provides a political and international framework. Together, they offer a fuller picture of how early Japan saw itself—both in terms of sacred origins and as a recognized state among its neighbors.

Influence Through the Ages

One of the greatest values of the Nihon Shoki lies in its scarcity as a source. Few records from ancient Japan survive, and the Nihon Shoki provides a continuous narrative of events, myths, and rulers in a single framework. Because of this, it became an essential text not only for cultural identity but also for academic research.

A Scholarly Window into the Past

For historians and archaeologists, the Nihon Shoki serves as a rare and invaluable reference point. As one of the few surviving chronicles of ancient Japan, it allows scholars to compare its accounts with archaeological sites and other records—separating historical fact from the realm of myth.

This blend of myth and history has made the text a central subject of intense scholarly research for centuries. It is not only a cultural treasure, but also a key to reconstructing Japan’s early past and understanding how the nation once viewed itself.

Mystery and Imagination

Within the text are stories of gods, legendary emperors, and mysterious beings whose existence may never be confirmed. These tales fuel the imagination, inspiring not only religion and tradition but also artistic expression across centuries.

In the performing arts, the Kabuki play “Nihon Furisode Hajime” dramatizes the hero-god Susanoo no Mikoto slaying the fearsome eight-headed serpent (Yamata no Orochi).

Visual arts also embraced these myths. In the Meiji era, the ukiyo-e artist Shunsai Toshimasa created prints such as Iwatokagura no Kigen, inspired by the Ama-no-Iwato (Heavenly Rock Cave) legend. Similarly, the late Edo master Tsukioka Yoshitoshi produced striking portraits of Emperor Jimmu, connecting legendary rulers to the visual imagination of his time.

Through Kabuki, ukiyo-e, and painting, the myths of the Nihon Shoki continued to inspire creativity, bridging the world of ancient chronicles with living art.

A small break — a little side note

A high-energy highlight reel from a live Kabuki staging of the classic myth. Bold performances, swirling robes, thundering nagauta music, and a towering serpent prop bring the Nihon Shoki legend of Susanoo vs. Yamata no Orochi to life—showing how myths recorded in the Nihon Shoki still come vividly to life on today’s Kabuki stage.

Cultural and Political Influence

At the same time, the Nihon Shoki reinforced the sacred legitimacy of the emperor and influenced Shinto rituals. By tracing the imperial line as a direct continuation from the age of the gods, it established the Japanese imperial house as the oldest continuing hereditary monarchy in the world.

Although today the emperor serves as a symbolic figure without political power, this unbroken lineage remains a defining feature of Japan’s national identity. The Nihon Shoki thus not only legitimized the authority of early emperors but also helped shape Japan’s enduring vision of itself as a nation rooted in both divine origins and historical continuity.

In short, the influence of the Nihon Shoki stems not only from its impact on faith, art, and politics, but from its very rarity and uniqueness as a source that continues to inspire curiosity, scholarship, and creativity.

Nihon Shoki in Modern Times

Today, the Nihon Shoki lives on not only as a subject of scholarship but also as a guide to sacred landscapes and cultural heritage sites across Japan. Many places mentioned in its pages are now famous tourist destinations that allow visitors to step into the world of myth and history.

-

Takachiho (Miyazaki) – Said to be the site of the Tenson Kōrin (Descent of the Heavenly Grandchild) and the Ama-no-Iwato cave where the sun goddess Amaterasu once hid.

Learn more on the official site -

Kashihara Jingū (Nara) – Built on the legendary site where Emperor Jimmu was enthroned, regarded as the birthplace of the Japanese nation.

Learn more on the official website here (Japanese only) -

Izumo Taisha (Shimane) – Associated with the myths of Susanoo no Mikoto and Ōkuninushi, gods of storms, land, and creation.

Learn more on the official site -

Ise Jingū (Mie) – The most important shrine dedicated to Amaterasu, the ancestral deity of the imperial family.

Learn more on the official site -

Asuka region (Nara) – The political and cultural heart of early Japan, filled with temples, tombs, and ruins connected to events recorded in the Nihon Shoki.

Learn more on the official website here (Japanese only)

By visiting these sites, one can experience how the stories of the Nihon Shoki still shape Japan’s cultural landscape and inspire both faith and tourism in the modern age.

Conclusion: Why the Nihon Shoki Still Matters

The Nihon Shoki is more than a book—it is a bridge between myth and history, legend and identity.

By weaving together creation stories, imperial genealogies, and diplomatic records, it established Japan’s place in the world while preserving its most ancient traditions.

Even today, its influence can be felt in the imperial institution, Shinto rituals, artistic creations, and cultural landscapes that trace their origins back to its pages. For scholars, it remains a vital key to understanding early Japan; for travelers, it offers a guide to sacred sites where myth and memory meet.

In the end, the Nihon Shoki invites us to see Japan not only as a modern nation, but as a civilization whose roots stretch into the realm of the gods—and whose story continues to inspire awe across the ages.