The Emperor of Japan: From Mythic Origins to a Modern Symbol of Unity

Did you know that long before prime ministers or parliaments existed, Japan was believed to be guided by a sovereign whose origins reached back to the gods?

At the center of this ancient tradition stands the Emperor of Japan.

And yet, the Emperor is far more than a figure from the past — he is a living symbol of tradition, spirituality, and continuity.

So who exactly is the Emperor of Japan?

How is he connected to the gods of Japan’s ancient myths?

What role has he played throughout history, and what does he represent today?

Let’s take a gentle journey from the origins of the imperial throne to its place in modern Japan.

Along the way, we’ll see how the Emperor continues to shape Japan’s identity — and why this unique institution still holds such deep meaning today.

Who Is the Emperor of Japan?

Let’s start by answering a simple but important question: what does “Emperor of Japan” actually mean today?

This section will guide us to that answer.

The Modern Emperor: A Symbol Beyond Politics

The Emperor of Japan (Tennō, 天皇) is the symbol of the nation and the unity of its people.

He does not govern the country or take part in politics.

Instead, the Emperor represents continuity, tradition, and a spiritual presence that links modern Japan with its long past.

In this sense, the Emperor carries out the role of preserving rituals, prayers, and cultural heritage — a role that makes him truly unique among the world’s heads of state.

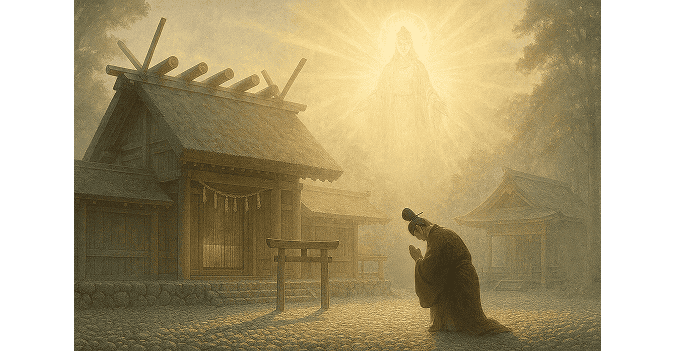

A Daily Role Rooted in Prayer

If the modern Emperor takes no part in politics, then what does he do each day?

One of his most important responsibilities is prayer.

At the Imperial Palace where the Emperor lives, daily rituals are performed to pray for the peace, safety, and well-being of the nation and its people.

In fact, Emperor Emeritus Akihito and Empress Emerita Michiko once stated that “prayer is the Emperor’s greatest duty.”

This shows how strongly the modern role of the Emperor remains connected to Japan’s ancient spiritual traditions, even under the present constitutional system.

Because of this deeply ritualistic role, many scholars describe the Emperor of Japan as the last living example of a “priest-king.”

A priest-king is a leader whose primary responsibility is spiritual rather than political.

Such figures once existed in many ancient civilizations, but today, Japan’s Emperor may be the only remaining example.

A Unique Continuity and Status

Another aspect that makes the Emperor truly unique is the extraordinary continuity of the imperial line.

According to tradition, the throne has been passed down through a male line of succession for more than 2,600 years.

This principle is still reflected in the modern Imperial Household Law (Kōshitsu Tenpan), which currently allows only male heirs to inherit the throne.

This remarkable continuity is closely tied to the Emperor’s special position in Japan today.

Although the Emperor lives within Japanese society, he is not recorded in the public family registry, and his status is defined directly by the constitution.

As the symbol of the State and the unity of the people, the Emperor is also subject to certain restrictions on personal freedoms and political activities, ensuring that the throne remains impartial and separate from everyday politics.

In this way, the imperial lineage handed down from ancient times — combined with a legal status distinct from that of ordinary citizens — has shaped the Emperor into a singular and deeply respected figure in modern Japanese society.

For these reasons, the Emperor of Japan is a symbolic figure who does not take part in politics, but represents the nation and its people.

Carrying forward traditions that stretch back more than 2,600 years, he offers daily prayers for the country and its citizens, and remains a uniquely respected and warmly regarded presence in Japanese society.

Origins: Myth and History

Where does the story of the Emperor begin, and how has it evolved over time?

Let’s trace the journey of the imperial line from its earliest origins to the present day.

Mythical Beginnings

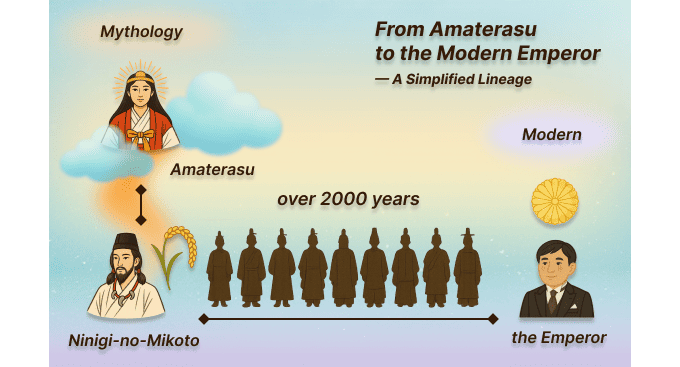

According to Japan’s oldest chronicles—the Kojiki (712 CE) and the Nihon Shoki (720 CE)—the story of the Emperor begins with the descent of Ninigi-no-Mikoto, the grandson of the sun goddess Amaterasu.

Ninigi is said to have come down from the heavens to bring order to the human world.

His great-grandson, Emperor Jimmu, is traditionally believed to have founded Japan in 660 BCE after a legendary journey known as the Eastern Expedition.

These ancient stories form the spiritual foundation of the imperial throne and have shaped the way the Emperor has been understood throughout the centuries.

From Myth to History

From a historical perspective, the earliest emperors are considered partly legendary, and the beginnings of the imperial institution look somewhat different.

Many scholars believe that the imperial system became historically recognizable during the Kofun period (3rd–5th centuries CE), when powerful rulers known as Ōkimi (“Great Kings”) began unifying the Yamato region.

During this early period, the Emperor was not only a spiritual figure but also the political leader who ruled the emerging Japanese state.

The first emperor often regarded as historically verifiable is Emperor Sujin, the 10th emperor in the traditional order, who is thought to have lived in the late 3rd to early 4th century.

The title “Tennō” (“Emperor of Heaven”) began to appear around the 7th century, during the time of Empress Suiko.

In the mid-7th century, under Emperor Tenmu, Japan adopted elements of the Chinese state system, forming a more formal and organized imperial government.

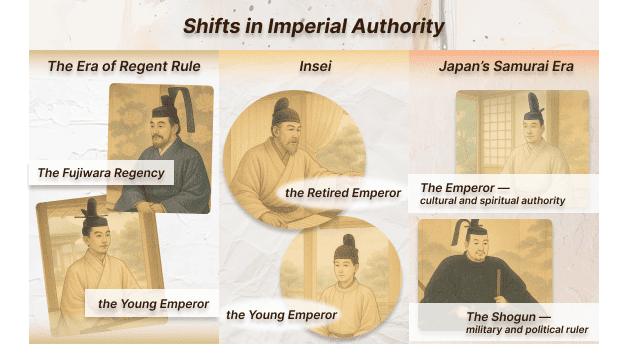

Changing Political Realities

After the imperial system became established, the balance of political power shifted many times throughout Japanese history.

-

Heian period (8th–12th centuries):

The Emperor continued to hold authority and remained the ultimate source of legitimacy, but real political power gradually moved into the hands of powerful aristocratic families such as the Fujiwara. -

Late Heian period (late 11th–12th centuries):

Political power shifted back toward the imperial side, as retired emperors—not the sitting emperor—governed the country through the insei (“cloistered rule”) system. -

Medieval to early modern era (12th–19th centuries):

Political authority eventually transitioned to the military governments of the Kamakura, Muromachi, and Edo shogunates.

Even as political power changed hands, the imperial institution itself was never abolished.

Throughout these eras, the Emperor continued performing rituals and remained the ultimate source of legitimacy for those who governed in his name.

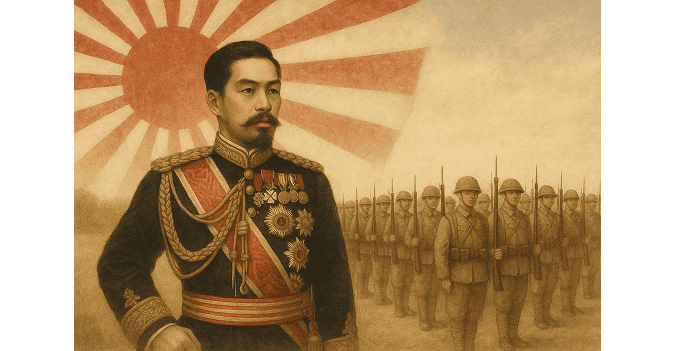

The Meiji Restoration and a Modern Monarchy

By the 19th century, the symbolic authority of the Emperor returned to prominence.

During the political turmoil of the late Edo period, both supporters and opponents of the shogunate began to place great importance on imperial legitimacy.

The Meiji Restoration (1868) then placed the Emperor at the center of a newly forming modern state.

He became the monarch of a constitutional system that blended traditional imperial symbolism with Western-inspired national reforms.

A small break — a little side note

Japan has had many emperors throughout its long history,

but do you know the emperor who led the nation from the age of samurai into the modern world?

That emperor is Emperor Meiji.

This video uses real photographs and historical artwork to explore his life — from political chaos and civil war to the rapid modernization that transformed Japan.

Whether you're interested in Japanese history or curious about the life of one of Japan’s most influential emperors, this video offers a fascinating glimpse into a remarkable era.

Enjoy the journey!

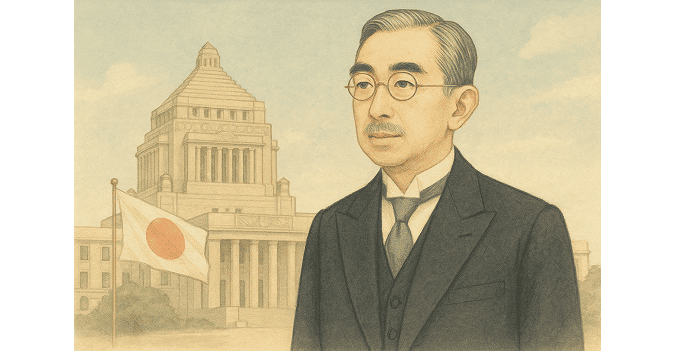

War and Postwar Transformation

In the 20th century, militarism began to rise in Japan.

Emperor Meiji and Emperor Shōwa witnessed not only the country’s rapid modernization but also the tragedies of war.

Historical records suggest that both emperors personally mourned Japan’s path toward conflict.

After World War II, Emperor Shōwa renounced all political authority.

Under the 1947 Constitution, the Emperor was redefined as a purely symbolic figure — a role that continues to shape the imperial institution today.

Beginning as a descendant of the gods, then ruling as an ancient sovereign, and finally becoming a modern symbol of peace and prayer, the role of the Emperor has transformed greatly over the course of history.

Yet the imperial institution itself — its lineage, rituals, and traditions — has continued unbroken for more than two thousand years.

It is a long and remarkable story that leads to the Emperor we know today.

Role in Shinto and Culture

We have already seen that one of the Emperor’s important roles is offering daily prayers for the nation.

But his contributions do not end there — the Emperor also plays a vital part in preserving Japan’s spiritual and cultural traditions.

In this section, we take a closer look at how the Emperor’s relationship with Shinto, rituals, and the arts has helped shape and sustain Japanese culture throughout history.

Sacred Ties with Ise Grand Shrine

One of the clearest expressions of the Emperor’s spiritual role can be seen in his connection to Ise Jingū, a shrine with a history stretching back more than 2,000 years.

More than a historical site, Ise Jingū is deeply significant because it enshrines Amaterasu, the sun goddess from whom the imperial line is traditionally said to descend.

For centuries, people in Japan have regarded the Emperor as a noble and respected figure — someone who watches over the nation and offers a sense of guidance and reassurance.

Because of this long-standing belief, Ise Jingū, with its sacred link to the origins of the imperial line, has become a powerful spiritual anchor for many.

Members of the imperial family regularly visit the shrine to pray for the country’s peace and prosperity.

These visits symbolize the idea that the Emperor remains close to the spiritual heart of Japan, providing a quiet sense of comfort and continuity for the people.

This tradition continues today and stands as one of the most vivid expressions of the Emperor’s symbolic and spiritual role in modern Japan.

Imperial Rituals and Enthronement Ceremonies

Many of the rituals and ceremonies associated with the modern Emperor are deeply rooted in Japan’s ancient traditions and cultural values.

Some of the most significant examples include:

-

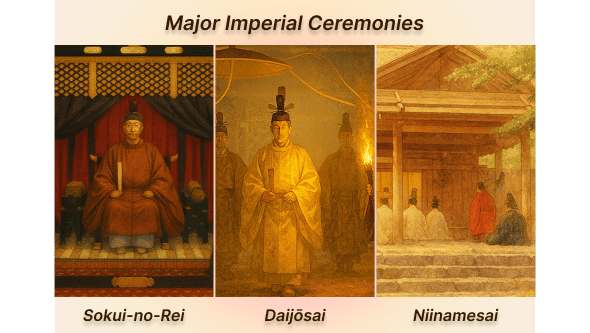

Sokui-no-Rei (Accession Ceremony):

A formal state ceremony that announces the new Emperor’s accession to the throne, both in Japan and abroad. -

Daijōsai (Great Thanksgiving Festival):

A once-in-a-lifetime rite performed only after a new Emperor ascends the throne.

In this sacred ceremony, the Emperor offers newly harvested rice to the deities and then partakes of it himself. -

Niinamesai (Harvest Festival):

An annual ritual in which the Emperor offers the year’s new rice harvest to the gods and then receives it as a divine blessing by eating it.

Among these, the Daijōsai holds particularly deep cultural meaning.

It is a one-time ceremony that expresses gratitude for peace and abundant harvests on behalf of the nation.

By offering rice to Amaterasu and other deities—and then partaking of the offerings—the Emperor symbolizes the close connection between the divine and the human.

This rite reflects Japan’s long history as a rice-growing culture, where agriculture, spirituality, and daily life have always been intertwined.

By preserving and performing these traditions, the Emperor helps carry Japan’s cultural memory into the future.

Patron of Arts and Tradition

The Emperor’s role is not limited to spiritual ties or the preservation of ancient rituals.

He also serves as an important supporter of Japan’s artistic and cultural heritage.

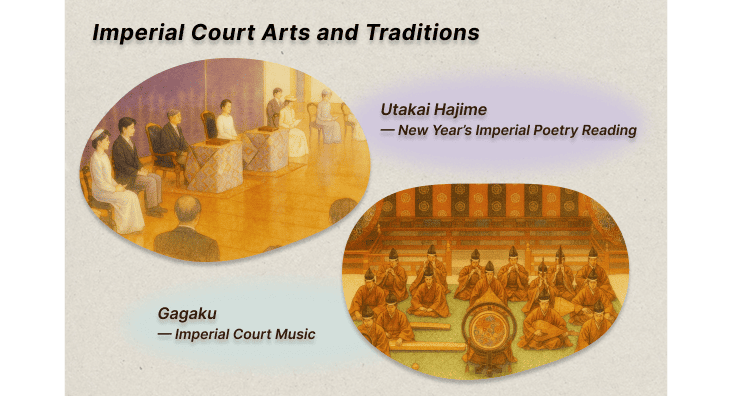

Throughout history, many emperors were accomplished poets, and under their patronage, the tradition of waka—classical Japanese poetry — flourished.

Today, this legacy continues through the annual Utakai Hajime, a New Year poetry ceremony held each January, where poems written by the public, the Imperial Family, and selected poets are presented before the Emperor and Empress.

Japan’s court music, gagaku, is another example of an art form sustained by the imperial tradition.

With a history of more than 1,200 years, it is considered one of the world’s oldest continuing musical traditions.

The Imperial Household Agency maintains an official ensemble, the Gakubu, which preserves and performs this ancient music to this day.

Through these traditions, the Emperor acts as a guardian who helps pass Japan’s cultural heritage on to future generations.

By supporting poetry, music, and seasonal rituals, the Emperor ensures that these living traditions continue to inspire the nation.

In this way, the Emperor is not only a historical figure, but also a guardian of Japan’s spiritual and cultural identity.

Through rituals, poetry, music, and ceremony, the imperial tradition continues to nurture some of the most enduring elements of Japanese culture today.

The Emperor in Modern Japan

In modern Japan, how does the Emperor connect with the people, and in what ways does he support the nation today?

In this section, we take a closer look at the Emperor’s place within Japanese society, and explore how his activities are linked to the daily lives of the people — providing a quiet sense of continuity, compassion, and unity.

A Presence of Comfort and Compassion

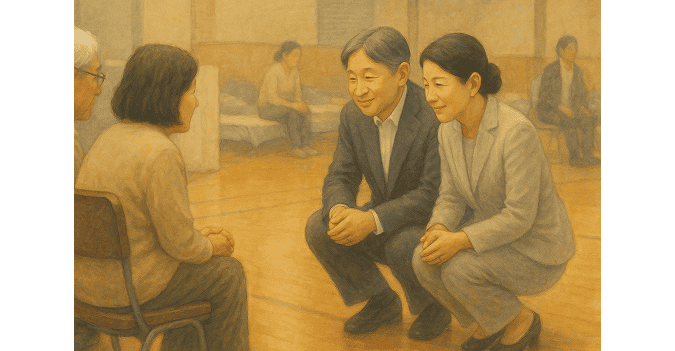

In modern Japan, one of the most important parts of the Emperor’s role is the way he stays close to the people.

When earthquakes, floods, or other disasters occur, the Emperor and Empress travel to the affected areas.

They sit with survivors, listen quietly to their stories, and offer gentle words of comfort.

These visits may seem simple, but in Japan they carry deep emotional meaning.

Kindness, humility, and empathy are highly valued, and the Emperor’s actions reflect these qualities in a very visible way.

For many people, meeting the Emperor during a difficult time brings a strong sense of encouragement.

His presence shows that the nation cares for them, and that they are not facing hardship alone.

Ceremonial Duties and National Milestones

The Emperor also appears at many important national events throughout the year — such as cultural celebrations, memorial services, and seasonal ceremonies.

When the Emperor attends these events, it gives them a special sense of importance and helps people feel that the whole country is sharing the moment together.

For many in Japan, seeing the Emperor at these occasions is a reassuring reminder of tradition, stability, and unity.

By taking part in these public milestones, the Emperor helps bring people together and highlights the values and customs that connect the Japanese nation across generations.

A Bridge to the World

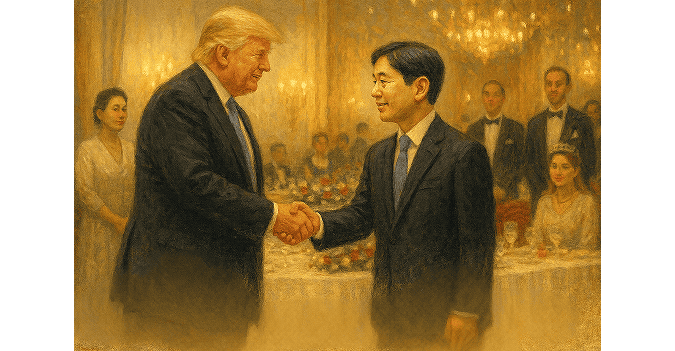

In the modern era, the Emperor also plays an important role on the international stage.

Through state visits abroad and welcoming foreign leaders to Japan, the Emperor and Empress help promote goodwill and mutual understanding between nations.

Their Majesties' presence highlights Japan’s cultural values in a warm and approachable way, offering an image of sincerity, respect, and harmony to people around the world.

By doing so, the Emperor and Empress contribute to strengthening Japan’s relationships with other countries and serve as gracious ambassadors of the nation.

A small break — a little side note

Want to see how Japan’s Emperor and Empress shine internationally?

In this video, you’ll get a close look at Their Majesties during their official visit to the United Kingdom, where they are warmly welcomed by King Charles and Queen Camilla.

The Emperor and Empress don’t represent Japan through politics — but through warmth, dignity, and genuine human connection.

If you’re curious about modern Japan, cultural exchange, or the unique role of the Japanese imperial family, this video is a great place to start!

Although the Emperor does not take part in governing the country, his presence is felt in many aspects of national life.

Through these activities, the Emperor gives shape to the idea of a symbolic leader: a figure who brings people together, offers comfort, and represents the heart of the nation in a uniquely Japanese way.

Symbolism and Global Comparison

We have explored the Emperor’s place and role within Japan — but how is the Emperor viewed from a global perspective?

In this section, we take a closer look at what makes Japan’s imperial institution unique among the monarchies of the world.

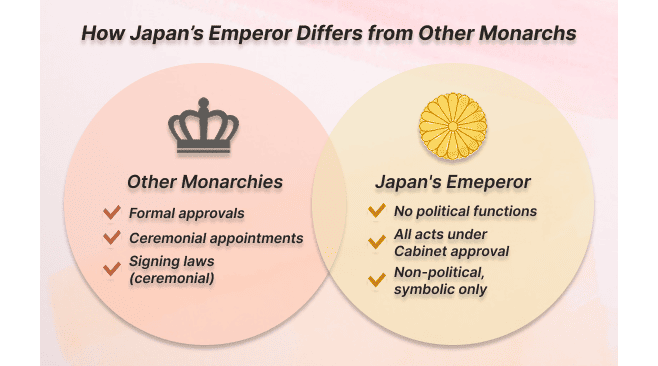

A Role Unlike Any Other Monarchy

The Japanese Emperor has characteristics that set him apart from other modern monarchs.

In countries such as the United Kingdom, Spain, and Sweden, kings and queens serve primarily as symbolic figures.

They do not make political decisions, yet they still carry out certain formal duties — such as signing laws or ceremonially appointing prime ministers — which remain part of the state’s constitutional processes.

Japan’s system differs under the 1947 Constitution.

The Emperor performs no political functions whatsoever — not even ceremonial approvals that other monarchs still undertake.

Every official act is carried out entirely under the advice and approval of the Cabinet, making the Emperor a fully non-political, symbolic figure.

This clear separation from political authority is one of the defining features that sets the Japanese Emperor apart from other monarchs today.

The World’s Oldest Continuing Dynasty

Japan is widely regarded as having the oldest continuing hereditary monarchy in the world, with a lineage stretching back more than two thousand years.

Across the globe, many royal houses have been overthrown, replaced, or vanished due to war and political upheaval.

Yet in Japan, the imperial line has continued from the nation’s earliest history to the present day.

Even during turbulent eras — such as the Nanboku-chō period, when rival courts claimed legitimacy — the line of imperial descent was never broken.

Throughout history, political authority shifted repeatedly: to regents, to warrior governments like the shogunate, and later to modern cabinets.

But the throne itself was never abolished, and the imperial lineage remained intact through every transition.

This exceptional continuity is unmatched anywhere in the world and remains one of the most defining aspects of Japan’s imperial tradition.

These features highlight why the Japanese Emperor holds such a distinctive place globally.

A monarchy without political authority yet sustained by extraordinary historical depth, the imperial institution continues to link Japan’s past, present, and future through its unique blend of ancient lineage and symbolic, non-political role.

Conclusion: A Timeless Symbol of Japan

Across over 2,000 years, the Emperor of Japan has continued to occupy a unique place in the nation’s life.

Though no longer a political ruler, the Emperor serves as a symbol of unity, continuity, and compassion, offering daily prayers for the country and standing close to the people in times of hardship.

Through rituals, poetry, and the preservation of ancient traditions, the Emperor helps carry Japan’s cultural heritage into the future.

And on the world stage, Their Majesties represent Japan with dignity and warmth, strengthening ties of friendship and mutual understanding.

Rooted in the world’s oldest continuing hereditary lineage, the imperial institution remains a living connection between Japan’s past and present — a role shaped not by authority, but by presence, tradition, and the enduring spirit of the people.