Yokai: Spirits Between the Seen and Unseen in Japanese Folklore

What if the shadow you glimpsed for just a moment had a name—and a story?

In Japan, something stirs in the forests, rivers, and quiet streets.

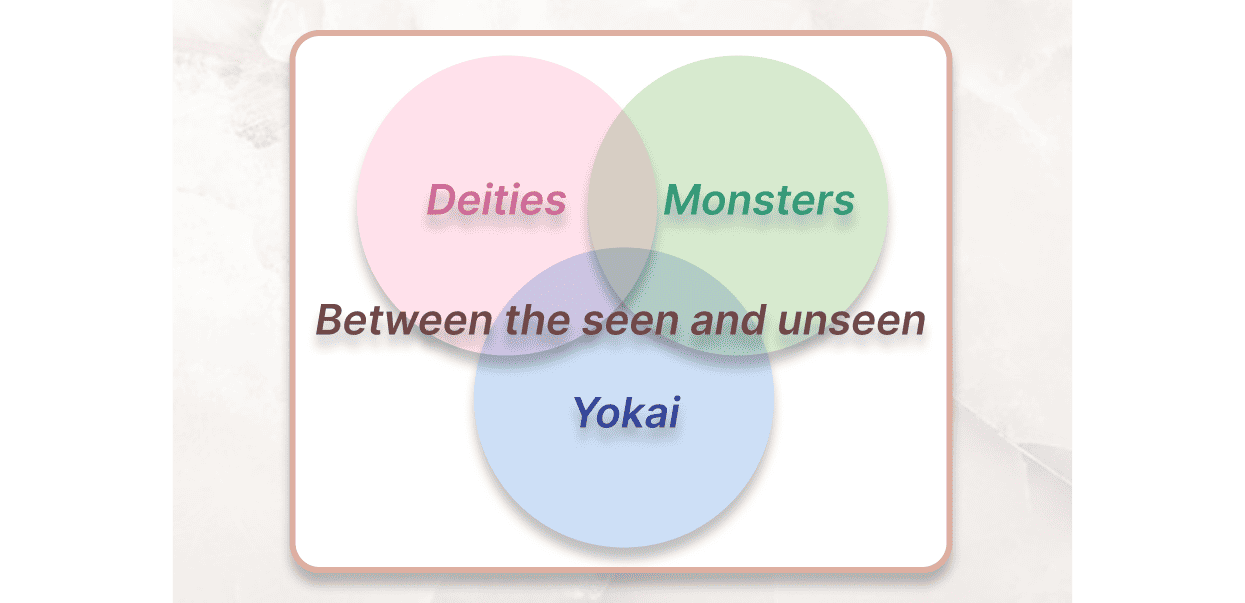

It is neither god nor monster—it is the yokai, a being that lives between the visible and the unseen.

For centuries, yokai have fascinated and frightened people alike.

They appear in ancient folktales, temple carvings, and even in today’s anime and games—mysterious presences that have never truly faded.

Come and explore their origins, their meaning, and how they continue to shape Japan’s imagination today.

What Are Yokai?

Let’s begin by asking a simple question—what exactly are yokai?

In Japanese folklore, yokai (妖怪) are mysterious beings that exist beyond human understanding.

They come in many forms and personalities. Some are:

- Strange or eerie in appearance

- Playful and mischievous

- Frightening or dangerous

- Kind and gentle

Yet they all share one purpose: to help people make sense of things that cannot be explained.

Yokai and the People Who Believed in Them

Yokai were deeply connected to how people in the past understood nature.

If you heard a strange sound deep in the forest, what would you think?

If you saw lights dancing on the surface of a river, how would you feel?

In old Japan, people didn’t see such things as science—or coincidence.

Instead, they whispered:

"Perhaps a yokai is behind it."

They imagined yokai taking many shapes.

Some appeared as clever foxes (kitsune) or playful raccoon dogs (tanuki), able to disguise themselves as humans.

Others, like the tengu (mountain spirits) or kappa (water imps), were believed to dwell deep within nature—sometimes helping, sometimes causing trouble.

Not Monsters, but Mirrors of Nature

Yokai are not simply “monsters.” They are something quite different from Western ghosts or creatures of horror.

In truth, yokai reflect an ancient Japanese belief that everything in nature has a soul— the wind, the river, even emotions themselves.

It is a worldview where every part of nature is alive and connected.

To understand yokai is to see the world through a different lens— to realize that every rustle, shadow, and whisper might hold an untold story.

Many Names, Many Natures: Other Words for Yokai

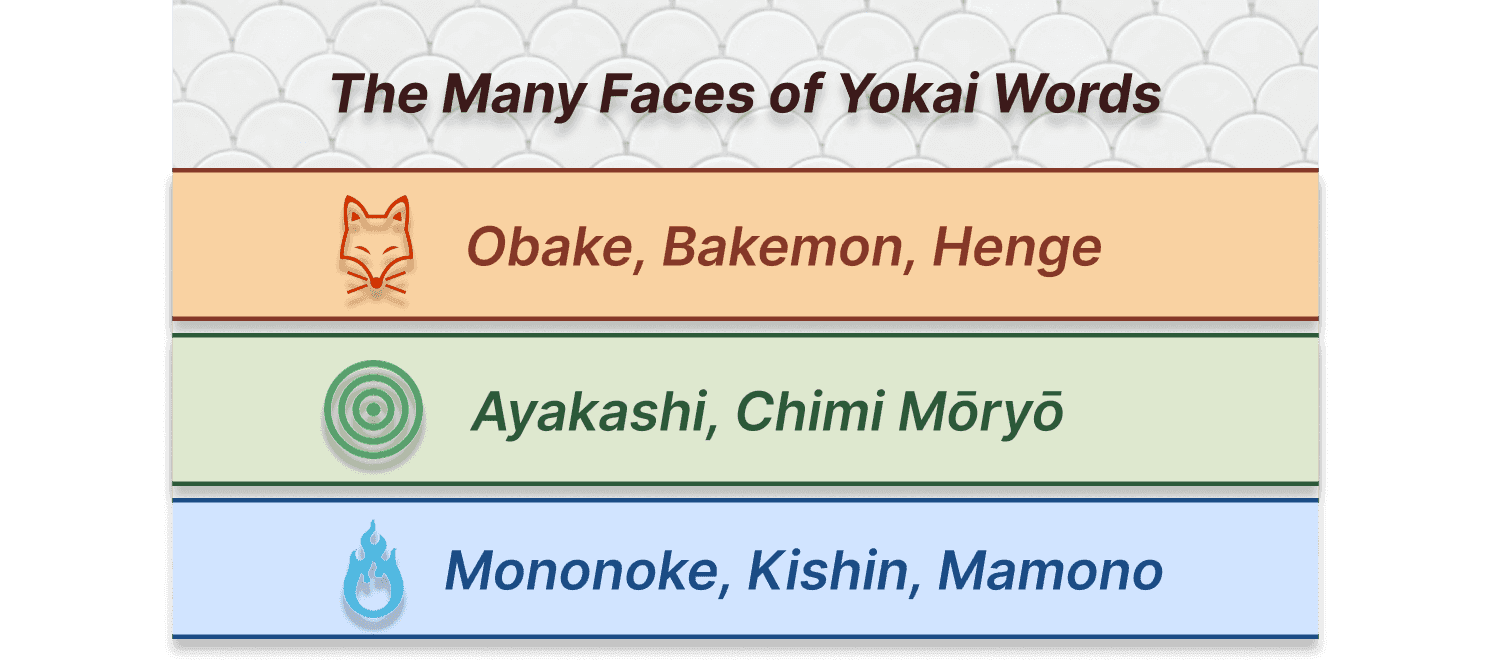

Did you know that the word “yokai” is just one of many names used to describe Japan’s mysterious beings?

In fact, throughout history, the Japanese language has offered many different words to express the strange and the unseen.

Let’s take a closer look at some of these other names for yokai.

Words and Meanings: The Many Names of Yokai

Below is a simple table showing the many names that belong to the family of “yokai.”

| Term | Japanese | Meaning / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Obake | おばけ | Shape-shifting spirits or friendly “ghosts”; still a familiar word among children today |

| Mononoke | 物の怪 | Mysterious or restless presences appearing in classical tales; often linked to illness or emotion |

| Kishin | 鬼神 | Fierce demon-deities or wrathful gods |

| Bakemono | 化物 | Transformed creatures or monsters that inspire both fear and awe |

| Ayakashi | 妖 | Eerie, ghostly presences said to appear near water or at twilight |

| Mamono | 魔物 | Cursed or demonic beings that embody chaos or darkness |

| Henge | 変化 | Shape-shifters, especially animals like foxes or raccoon dogs |

| Chimi Mōryō | 魑魅魍魎 | An old poetic phrase describing countless untamed spirits of nature |

Isn’t it fascinating how rich and detailed these expressions are?

Over the centuries, people have used them freely—sometimes playfully, sometimes seriously—depending on the story, the region, or even the mood of the moment.

This shows just how deeply people’s curiosity and imagination were drawn toward the unseen world.

The words for "yokai" and their many companions reveal that, for the Japanese, these mysterious beings were never distant—they were part of everyday life.

The Origins and History of Yokai

Where did yokai come from?

Their roots reach deep into Japan’s ancient beliefs, myths, and everyday life.

Over time, these mysterious beings evolved—from sacred spirits to the colorful characters we know today.

Let’s take a closer look at how yokai began—and how they transformed through history.

Ancient Roots: Spirits in Nature

Long before the word "yokai" existed, the people of ancient Japan believed that everything in nature had a spirit.

Thunder, wind, trees, rivers—even illness and emotions—were thought to have a will of their own.

Stories in the ancient texts like the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki speak of gods, monsters, and strange events that blurred the line between the natural and the supernatural.

These early tales planted the seeds of what would later be called yokai.

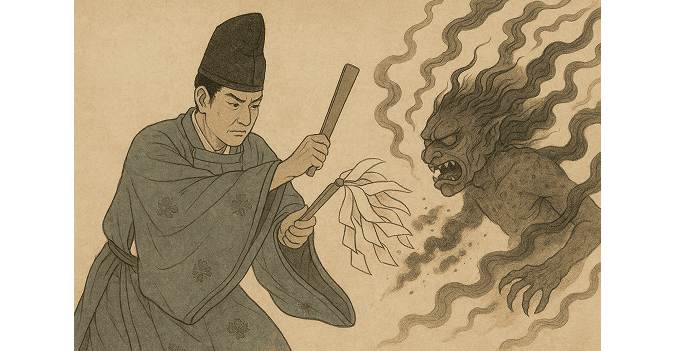

Heian Period: The Age of Spirits and Superstition (794–1185)

As Japan’s capital life flourished in Kyoto, people became more and more interested in the unseen world.

Strange things—illness, bad dreams, or mysterious sounds—were not seen as ordinary problems. Many believed they were caused by spiritual forces or by feelings that had turned dark or unbalanced.

This was the time of onmyōdō, a practice that tried to understand and control such unseen powers, and the age of mononoke—restless spirits thought to bring misfortune.

Even in elegant stories like The Tale of Genji, characters suffer not from ghosts, but from emotions so strong they become living spirits, called ikiryō.

It was a time when fear, faith, and imagination were closely linked—a world where feelings could shape reality itself.

Medieval Japan: From Fear to Story

During the Kamakura and Muromachi periods (1185–1573), yokai began to appear in art—in paintings and picture scrolls known as emaki.

Artists gave form to invisible fears, drawing demons, long-necked women, and one-eyed monks wandering through the night.

Through these works, yokai slowly began to develop their own identities and personalities.

What had once been religious warnings turned into stories that reflected both fear and curiosity—tales meant not only to caution, but also to entertain.

At first, such scrolls were kept by temples, nobles, and warriors.

But over time, these stories spread among the common people, whispered and retold beside flickering lamps.

At last, the unseen had taken shape.

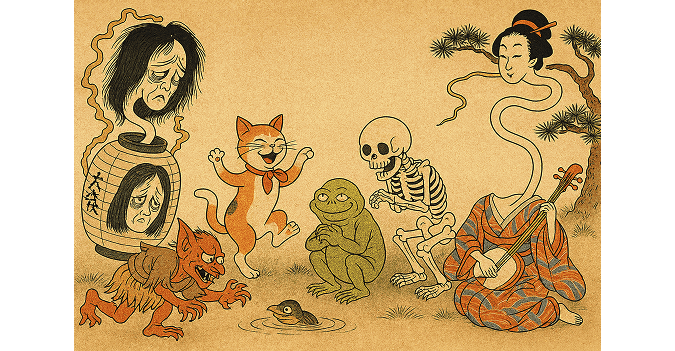

Edo Period: Yokai for Everyone

During the Edo period (1603–1868), yokai became a part of everyday popular culture.

They appeared in woodblock prints (Ukiyo-e), picture books, and even children’s games, often drawn with a sense of playfulness.

Artists like Toriyama Sekien created detailed encyclopedias of yokai, giving each spirit a name, a story, and a personality of its own.

Yokai became friendly companions of daily life—appearing on clothing, toys, and festival decorations.

No longer beings to be feared, they came to represent creativity, imagination, and humor in the world of Edo.

Meiji to Modern Times: From Superstition to Culture

In the late 19th century, as Japan opened its doors to the modern world, belief in yokai began to fade.

Western science and education dismissed them as superstitions—old relics of the past.

Yet the stories of yokai never truly disappeared.

Folklorists such as Kunio Yanagita and artists like Shigeru Mizuki revived interest in these mysterious beings, preserving local legends and breathing new life into them through literature and art.

Even today, yokai continue to live on—not as things to fear, but as a window into how the Japanese people understand nature, mystery, and the human heart.

To follow the history of yokai is to follow the story of Japan itself.

It shows how the Japanese people have expressed the unseen—transforming fear into familiarity, and learning to live alongside the mysterious.

Types of Yokai in Daily Life: Fear, Fortune, and Function

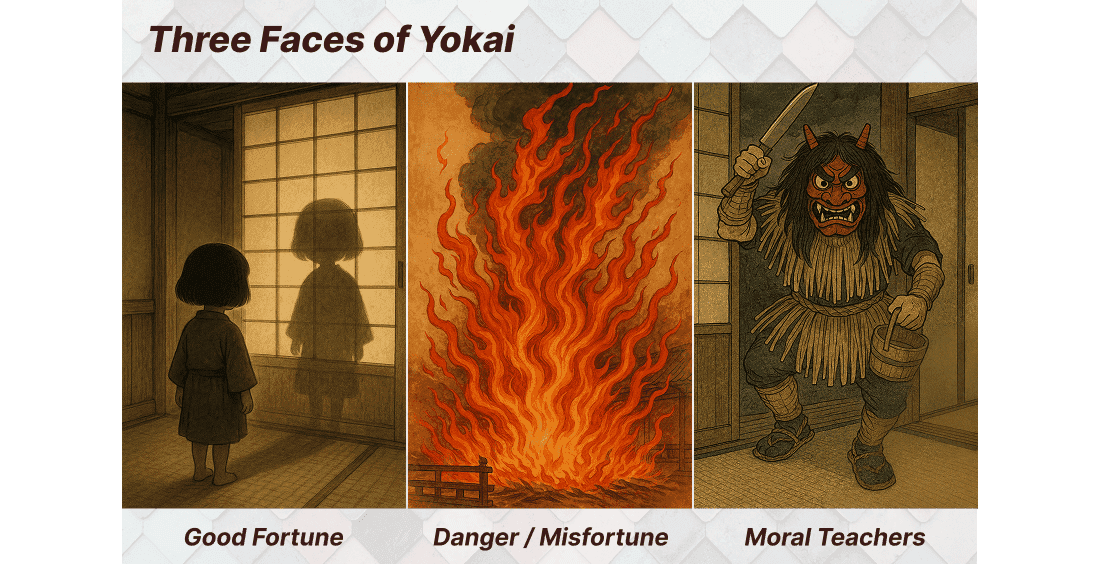

Although yokai appeared in countless shapes and personalities, they can be broadly divided into three main types, each with its own role and meaning.

Let’s take a closer look at these categories and the roles they played in people’s lives.

1. Yokai of Good Fortune

Not all yokai were frightening or harmful. Some were believed to bring happiness, prosperity, and protection to those who treated them well.

One well-known example is Zashiki-warashi—a playful child spirit said to quietly dwell in a family’s guest room.

If treated with kindness and respect, it would bring joy and wealth to the family. But if ignored or angered, it was said to disappear, taking good fortune along with it.

The boundaries between folk belief, deity, and myth were often blurred, and yokai themselves came to be seen as guardian-like spirits, deeply woven into the fabric of everyday life in Japan.

A small break — a little side note

What kind of yokai is Zashiki-warashi?

This short video introduces this beloved spirit from Japanese folklore.

You may not see Zashiki-warashi, but you can often feel its presence. It might seem a little eerie, but there’s no need to be afraid. Homes where this spirit dwells are said to be protected and blessed with good fortune.

But what happens when the Zashiki-warashi disappears…? Find out more about this mysterious bond between people and their unseen guardian.

2. Yokai of Danger and Misfortune

Of course, where there were kind spirits, there were also those to be feared. Some yokai were believed to cause disasters, illness, and strange misfortunes that people could not explain.

A sudden fire might be seen as the anger of a fire god or spirit, while a poor harvest or mysterious sickness could be blamed on unseen, malevolent forces.

By believing in these yokai, people found a way to make sense of hardship—responding through rituals, prayers, and offerings to calm the unseen world.

In this belief, people gave these unseen forces a shape and name through yokai, allowing them to express both gratitude for nature’s blessings and awareness of its hidden dangers.

3. Yokai as Moral Teachers

Yokai also played the role of teachers and storytellers, helping to pass down lessons about good behavior and community values—especially to children.

In Akita Prefecture, for example, the fearsome Namahage—a demon-like figure wearing a mask—was said to visit homes on New Year’s Eve, warning lazy or disobedient children to change their ways.

Similar tales were told all across Japan. Through these stories, yokai acted as moral guides, reminding people to work hard, respect others, and follow local customs.

In this way, yokai became part of Japan’s living tradition—a way for communities to teach, protect, and preserve their values across generations.

Through these many roles, yokai became far more than just spooky legends.

They helped people make sense of the unseen, offering explanations for everything from everyday misfortunes to unexpected blessings.

Ultimately, yokai formed a shared cultural language—a way for people to understand the world around them, and to express both fear and gratitude toward the mysteries of life.

Nature, Seasons, and the Spirit World

So far, we’ve seen how yokai serve as one way to give shape to the unseen. But what gave rise to such expressions in the first place?

The answer lies in the Japanese people’s deep sensitivity to nature, time, and emotion.

In this section, we’ll explore how this awareness shaped the way yokai were imagined.

Liminal Moments and Spiritually Charged Spaces

For centuries, Japanese people have been drawn to transitional moments—the quiet spaces that exist between one world and another.

These include:

- The soft light of dusk, when shadows blur the edge of the world

- Mountain paths and riverbanks, where nature and people meet

- The change of seasons, when the air feels full of uncertainty

- Places filled with silence, solitude, or still emotion

These “in-between” times were seen as both beautiful and mysterious. It was believed that yokai appeared during such moments, when the boundaries between the visible and the invisible grew thin.

This way of sensing something beyond what can be seen became an important part of Japan’s view of nature.

Yokai can be understood as one way people gave form to this awareness.

Giving Shape to the Invisible

In Japanese tradition, the unknown is not something to be feared or denied.

Instead, it is often accepted and given a shape, a name, and a story—turning unseen forces into familiar presences like yokai.

Not everything must be visible to be real. Even the unseen can be felt and understood as part of the world.

For many Japanese people, yokai symbolized this idea—that mystery is not something to avoid, but something to recognize and live with.

Famous Yokai of Japan

By now, you’ve learned how yokai have been imagined and understood throughout Japan’s history.

But you may be wondering—what kinds of yokai actually exist?

In this section, we’ll meet some of Japan’s most famous and beloved yokai, each with its own unique story, character, and charm.

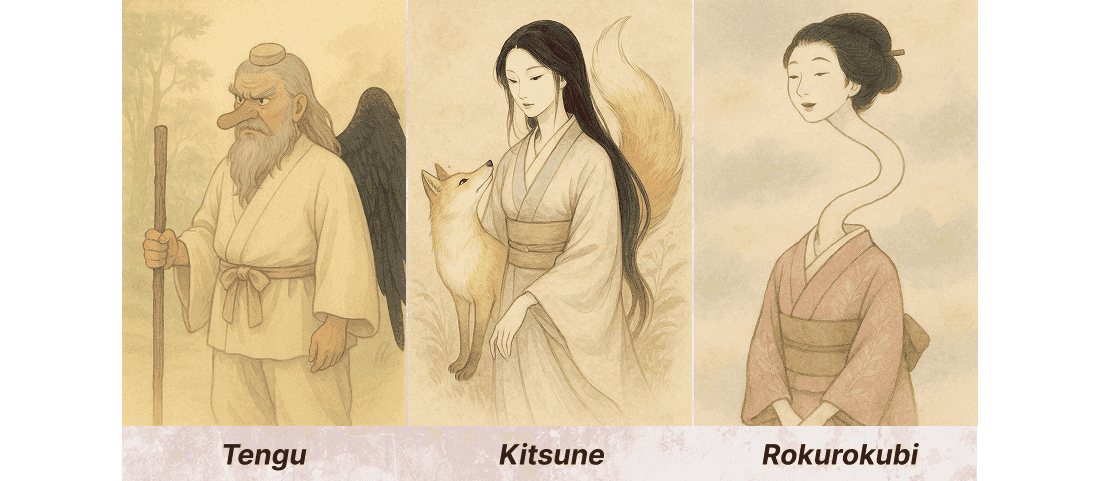

Tengu – The Mountain Goblin

Tengu are powerful, long-nosed beings who dwell deep in the forests and mountains.

Once feared as dangerous spirits who misled monks and travelers, they later came to be seen as guardians of sacred peaks and skilled masters of martial arts.

Their dual nature—both wrathful and protective—symbolizes the awe and respect people have long held toward the mountains of Japan.

Kitsune – The Shape-Shifting Fox

Kitsune, or fox spirits, are among the most famous yokai in Japan.

Known for their intelligence and magical powers, they can take on human form—often appearing as beautiful women or mysterious travelers.

Some serve the rice deity Inari, bringing prosperity and good harvests, while others play tricks on humans through illusion.

They show that the boundary between the human and spirit worlds is never entirely clear.

Rokurokubi – The Long-Necked Woman

By day, Rokurokubi appear as ordinary women.

But at night, their necks stretch to impossible lengths, revealing a hidden nature that terrifies those who see it.

In some tales they are cursed, in others mischievous.

Their unsettling transformation reflects the fear—and fascination—of what may hide beneath the everyday.

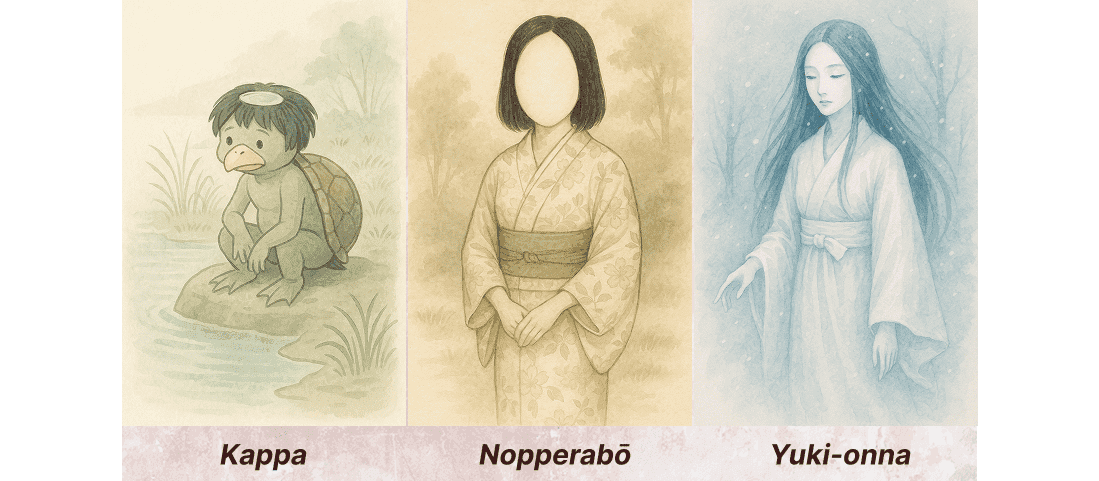

Kappa – The Mischievous River Imp

Kappa are amphibious yokai who inhabit Japan’s rivers and ponds.

Small in stature with a dish of water atop their heads, they are known for their pranks and love of cucumbers.

It is said that if you bow to a kappa, it will politely bow back—but when it does, the water from the dish on its head spills out, and the creature instantly loses its strength.

They also teach respect for waterways and nature’s hidden power.

Nopperabo – The Faceless Ghost

At first glance, a Nopperabo looks like an ordinary person.

But when they turn to face you, their features vanish—leaving only a smooth, blank face.

They rarely harm anyone, yet their eerie appearance evokes the unsettling sense that something familiar can suddenly become strange.

Yuki-onna – The Snow Woman

The Yuki-onna is one of Japan’s most hauntingly beautiful yokai.

Dressed in white and surrounded by snow, she appears on winter nights—sometimes to guide lost travelers, other times to lead them to their frozen fate.

She embodies the elegance and danger of winter itself—beautiful, cold, and fleeting.

Yokai in Modern Media and Pop Culture

Although yokai have ancient origins, they continue to live vividly in modern Japanese culture.

Today, they are reimagined through books, films, games, and even daily life—taking on new, creative forms of expression.

Let’s take a closer look at how yokai appear in Japan today.

Manga and Anime

-

GeGeGe no Kitaro by Shigeru Mizuki

One of Japan’s most beloved yokai series, it follows Kitaro, a boy from the “Ghost Tribe,” and his eyeball-shaped father as they encounter all kinds of spirits.

The story explores the delicate balance between humans and yokai, showing that neither side is purely good nor evil.

Sometimes Kitaro protects humans; other times, he defends the yokai themselves. -

Natsume’s Book of Friends (Natsume Yūjinchō)

A gentle and heartfelt story about a boy named Natsume, who inherits a mysterious book from his grandmother—filled with the names of yokai she once bound through magical contracts.

As Natsume meets these spirits, he strives to return their names and set them free, quietly forming warm, emotional bonds along the way.

The series beautifully explores the themes of memory and connection between humans and yokai.

A small break — a little side note

Have you ever wondered what kind of yokai appear in GeGeGe no Kitaro? If you’re curious, check out this video—it’s the series’ famous theme song!

The song is in Japanese, but the melody is so catchy that you’ll find yourself humming along. Its slightly spooky tune and the atmosphere of all kinds of yokai make it feel a little mysterious—maybe even a bit grown-up.

Even if you don’t understand the words, you can still feel the rhythm and mood that bring Kitaro, Medama-oyaji, and their yokai friends to life. A true classic of Japanese culture!

Film and Television

-

Spirited Away (Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi) – Studio Ghibli

Hayao Miyazaki’s Academy Award-winning masterpiece brings to life a world of spirits, gods, and yokai inspired by Japan’s ancient belief in Yaoyorozu no Kami—the “eight million gods.”

Characters like No-Face (Kaonashi) and the bathhouse spirits create a world that is mysterious, emotional, and deeply rooted in Japanese imagination. -

The Great Yokai War (Yōkai Daisensō) – Takashi Miike

A live-action fantasy adventure where a young boy becomes part of an ancient battle.

Classic yokai from folklore unite to face a dark army born from forgotten grudges and fading traditions—a story that reflects Japan’s tension between past and present.

Games and Interactive Media

-

Yo-kai Watch

A fun and playful series that brings the world of traditional yokai into the modern age.

Players collect and befriend various yokai, discovering that even the most mischievous ones can become trustworthy companions.

Designed for younger audiences, the series reimagines yokai in a friendly and relatable way for today’s generation. -

Nioh

A dark, action-packed journey through a mythic version of Japan’s Sengoku period.

Players take on the role of a foreign samurai battling fearsome yokai drawn directly from traditional legends—merging history, folklore, and fantasy into one.

In this way, the world of yokai has expanded—from the realm of folklore and belief to the colorful world of pop culture.

What was once felt only through imagination has now taken visible form—brought to life as characters that move, speak, and connect with people in new ways.

Yokai continue to evolve with the times, proving that the mysterious can still live side by side with the familiar.

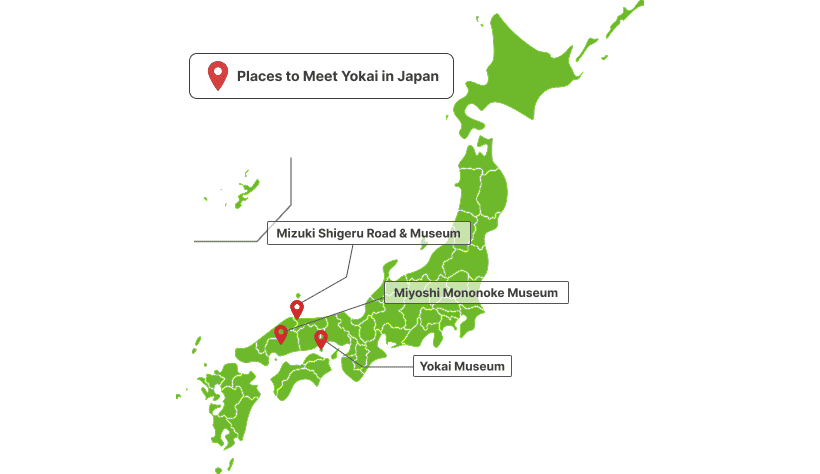

Where to Experience Yokai in Real Life

Did you know that in Japan, there are places where you can meet yokai up close—not just through a screen or a story?

Here are a few destinations where you can experience these mysterious beings more personally, through art, history, and imagination.

Mizuki Shigeru Road & Museum (Sakaiminato, Tottori)

In the seaside town of Sakaiminato, Tottori Prefecture—the birthplace of manga artist Shigeru Mizuki—you can stroll down a street lined with over 170 bronze statues of his beloved yokai characters from GeGeGe no Kitaro.

Shops sell yokai-themed souvenirs and snacks, while the Mizuki Shigeru Memorial Museum offers an intimate look at his life, artwork, and deep affection for the spirits that inspired generations.

Miyoshi Mononoke Museum (Miyoshi, Hiroshima)

Located in Hiroshima Prefecture, this museum invites visitors to explore the folk origins and regional legends of yokai.

It’s both educational and entertaining, featuring interactive exhibits and historical artifacts that bring Japan’s mysterious traditions to life.

Often called Japan’s first full-scale yokai museum, it’s a perfect place to see how these stories continue to evolve even today.

Yokai Museum (Shodoshima, Kagawa)

On Shodoshima Island in Kagawa Prefecture, this creative museum transforms historic buildings into a modern space for yokai art.

It blends folklore with contemporary design, turning eerie legends into beautiful, thought-provoking installations.

It’s a one-of-a-kind experience where visitors can see how ancient imagination meets modern creativity.

Conclusion: Why Yokai Still Matter

Yokai are not simply old legends or frightening creatures.

They embody the Japanese way of embracing nature, the unknown, and the emotions hidden in everyday life—not with fear, but with gentle acceptance.

From ancient picture scrolls to modern anime and games, yokai have continued to evolve, carrying timeless questions and feelings that never fade across generations.

In a world that often seeks clear answers, yokai teach us that there is meaning in mystery itself.

Perhaps we, too, can sometimes pause—and simply feel the things that cannot be put into words, listening to the quiet stories whispered in the shadows.