Oni: Japan’s Demons of Fear, Faith, and Fortune

Imagine a giant with crimson skin, wild hair, and a tiger-skin loincloth, swinging a spiked iron club with terrifying strength.

Frightening? Certainly.

In Japan, this being is known as the Oni—a symbol of fear, punishment, and power that has haunted people’s imagination for centuries.

At first glance, Oni may seem similar to demons or ogres from Western legends.

But unlike those figures, Oni are not simply embodiments of evil.

They can punish, protect, or even bless—revealing both the dark and the noble sides of human nature.

So what exactly are they, and how have the Japanese come to understand them?

When fear turns into faith, and demons reflect what it means to be human, the world of the Oni reveals itself—a mysterious realm where power, terror, and reverence come together.

Let’s step into that world together.

What Is an Oni?

Before diving into myths and legends, let’s start with the basics.

What exactly are Oni—and why have they remained such unforgettable symbols of Japan’s imagination for so long?

In Japanese folklore, Oni (鬼) are among the most recognizable yokai—supernatural beings that show the darker side of human nature.

They appear in countless myths, folktales, and local traditions across Japan, representing fear, punishment, and raw power—forces that test human courage and morality.

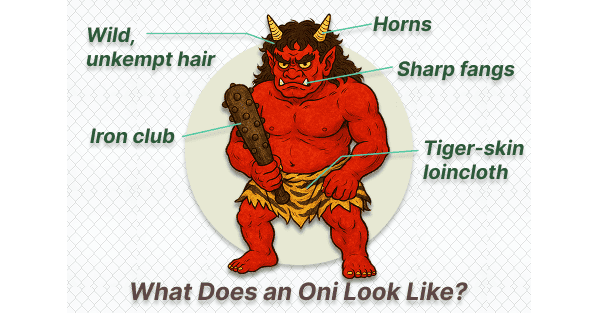

Appearance: Strength and Terror Combined

They are usually shown as huge, frightening figures with:

- Horns growing from their heads

- Sharp fangs and wild, unkempt hair

- A tiger-skin loincloth, marking their untamed nature

- A heavy iron club (kanabō), symbolizing overwhelming strength

Their fearsome look makes them instantly recognizable—and impossible to forget.

Oni in Everyday Life

Even today, Oni remain part of daily life in Japan—as symbols of evil and bad luck that people try to drive away.

During the annual Setsubun festival, families throw roasted soybeans while shouting “Oni wa soto! Fuku wa uchi!” (“Demons out, good fortune in!”).

In this ritual, the Oni represent invisible forces of misfortune and impurity—what the Japanese call jaki (邪気).

Throwing beans at them is believed to cleanse the home and invite good luck for the year ahead.

In this way, Oni—though feared as monsters—remain familiar figures in Japan even today, reminding people how deeply they are woven into the country’s culture, imagination, and spiritual life.

Origins and Mythology

The Oni is often seen as a frightening creature—but throughout Japanese history, it hasn’t always been a symbol of fear.

Beyond their scary appearance, Oni have also been worshiped as divine beings and shown as teachers of moral lessons in stories and traditions.

Let’s look at three key stages in Japanese history that reveal how the Oni came to have such deep and complex meanings.

1. Divine Origins and Chinese Influence

In ancient Japan, the word oni did not originally mean something evil.

In fact, it referred to sacred spirits—messengers of the gods or mountain deities—that existed in the unseen world between humans and the divine.

Everything began to change in the 6th century, when Buddhism and Chinese culture arrived in Japan.

The Chinese character 鬼 (gui)—meaning “spirit of the dead”—was adopted, bringing new ideas about the afterlife and unseen forces.

As these ideas blended together, oni changed from sacred spirits into mysterious beings standing between the divine and the supernatural—not entirely good or evil, but powerful and unpredictable.

2. From Sacred Spirit to Fearsome Monster

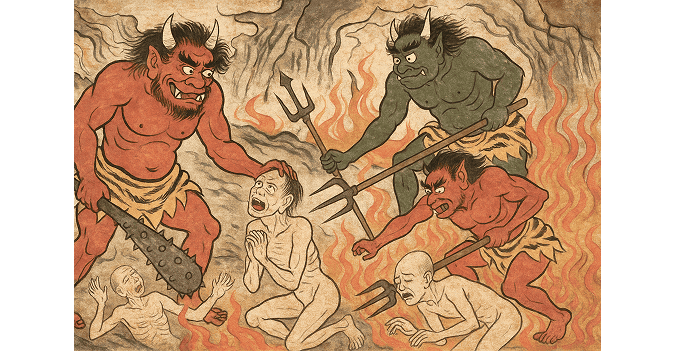

By the Heian period (794–1185), Oni had become much darker in the Japanese imagination.

They appeared in legends as man-eating monsters and vengeful spirits, born from human emotions such as anger, jealousy, and hatred.

Some stories even warned that people consumed by such emotions could turn into Oni themselves.

This change reflected a mix of Shinto beliefs and Buddhist ideas about demons in hell (gaki) who punish the wicked.

Through this fusion, Oni became symbols of punishment and chaos, showing both the moral cost of human sin and the fear of the unknown.

The terrifying Oni of this era—wielding clubs, devouring humans, and haunting the unseen world—formed the image that still lives in Japanese culture today.

3. Folktales of Fear and Fortune

From the Muromachi (1336–1573) to the Edo period (1603–1868), the Oni’s image evolved once again.

While still feared, they began to appear in folktales not only as villains but also as complex beings who could teach lessons—or even bring good fortune.

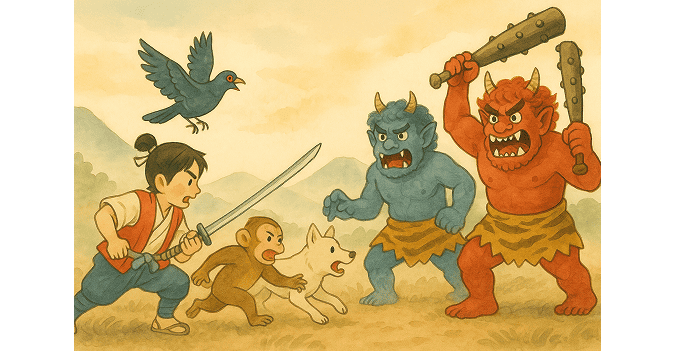

In famous stories such as Momotaro (The Peach Boy) and Shuten-dōji, Oni clearly represent evil and are defeated by human heroes.

But in tales like Kobutori Jiisan (“The Old Man with a Lump”) and Mame-tsubu Korokoro (“The Rolling Bean”), Oni are not villains.

Instead, they become unexpected bringers of fortune, leaving behind treasures and lessons about greed and kindness, and humility.

Through these stories, Oni are seen not just as monsters, but as mirrors of human emotion—showing that even frightening beings can reveal important truths about the heart.

Even today, Oni remain deeply rooted in Japanese culture—feared as symbols of evil and misfortune, yet remembered through stories that teach moral lessons and cultural values passed down for generations.

A small break — a little side note

Ever wondered how Oni appear in Japanese folktales?

This short animated video tells the well-known story of Kobutori Jiisan (“The Old Man with a Lump”).

In the tale, a kind old man and a greedy one both encounter the Oni—but with completely different endings.

Today, this story is often shared with children through charming animations like this one, passing down lessons of kindness and humility.

What kind of moral message do the Oni teach through these two old men?

Watch and find out!

Appearance and Symbolism

As we’ve already seen, Oni are easy to recognize by their horns, fangs, and tiger-skin loincloth.

But their appearance carries deeper meaning—each feature reflecting the emotions, desires, and weaknesses that live inside the human heart.

In this section, let’s look at how the Oni’s form expresses the moral and spiritual struggles of humanity.

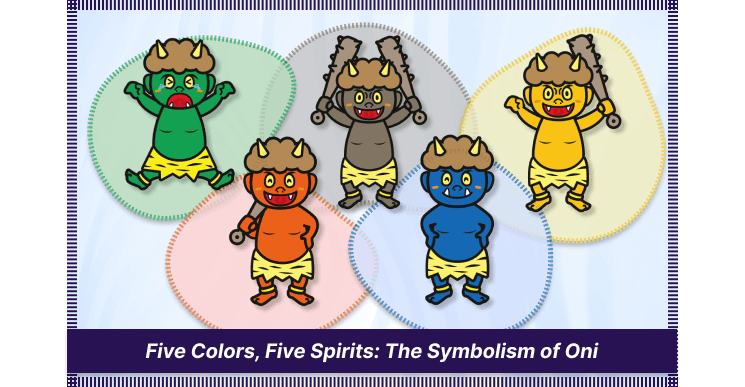

Colors and the Emotions Within

When you look closely, you’ll notice that Oni appear in many colors—each with its own meaning.

In Buddhist thought, these colors are linked to the five hindrances of the human mind (gokai)—spiritual obstacles like desire, anger, and doubt.

These emotions represent the darker feelings that disturb the heart and lead people away from harmony.

| Oni Color | Symbolism | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Red Oni | Greed and craving (tonyoku) | The most iconic Oni, often shown gripping a heavy spiked club. |

| Blue Oni | Hatred and anger (shin’i) | During Setsubun, people throw beans at blue-faced Oni to drive away these emotions and invite good fortune. |

| Yellow / White Oni | Attachment and regret (jōko) | Sometimes shown carrying a saw, symbolizing emotional clinging and sorrow. |

| Green Oni | Laziness and indulgence (konchin) | Often shown with a naginata (pole weapon) and linked to prayers for good health. |

| Black Oni | Doubt and suspicion (gi) | Usually shown wielding an axe, representing mistrust and inner conflict. |

Together, these colors show that Oni are more than monsters—they are reflections of the human heart, each color expressing a different struggle within us all.

The Iron Club (Kanabō)

The Oni’s most famous weapon—the iron club (kanabō)—also carries spiritual meaning.

Its origins go back to an ancient ritual staff called saibō (“spirit-purifying rod”), once used by hōsōshi (exorcists) to ward off evil and impurity.

In those days, it wasn’t a weapon of destruction, but a sacred tool for cleansing unseen energy.

Over time, this ritual staff turned into a weapon covered with iron studs, called kanasaibō—literally the “demon-crushing rod.”

Its heavy weight and unstoppable force gave rise to the image of the Oni wielding a weapon that nothing could resist.

In Japanese, there’s even a saying:

"Oni ni kanabō" (鬼に金棒) — an Oni with an iron club.

This proverb means someone who is already strong or skilled becoming even stronger—truly unbeatable.

To the Japanese imagination, an Oni holding a kanabō represents the ultimate form of strength—both feared and admired.

It reflects not only the terror of power, but also humanity’s wish to possess such unshakable strength.

In this way, Oni—through their form and symbolism—represent human imperfection and inner struggle.

Their bright colors and overwhelming power reflect something deeper inside us: a longing to rise above our weaknesses and live with courage, resilience, and dignity, even in the face of unseen forces that shape our lives.

Oni in Festivals and Traditions

We’ve already seen how Oni appear in everyday life through the Setsubun bean-throwing ritual.

Beyond Setsubun, however, there are many traditional ceremonies and festivals across Japan where Oni take on deeper and more sacred roles.

In this section, let’s explore two of the most remarkable temple festivals.

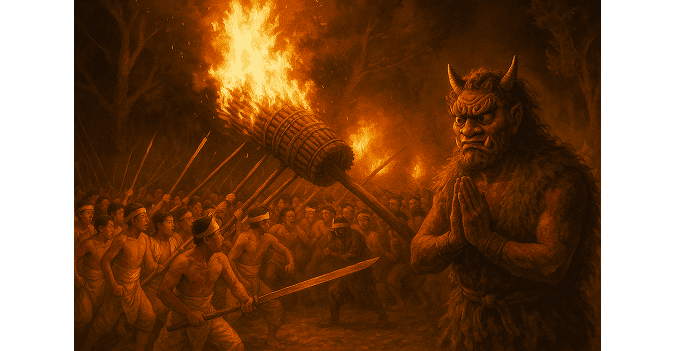

Oniyo (Fukuoka) — The Fire of Purification

Held at Daizenji Tamataregu Shrine in Kurume City, Fukuoka Prefecture, the Oniyo Fire Festival is one of Japan’s three great fire festivals.

It takes place during the New Year’s Oni-e rituals, which run from New Year’s Eve to January 7.

During this powerful event, men carry huge burning torches through the shrine grounds, lighting up the night with roaring flames.

It is believed that being showered with sparks from these torches brings good health, safety, and prosperity for the coming year.

The festival comes from an ancient tsuina ceremony—a ritual to drive away evil spirits and disease.

In this rite, the Oni appear as symbols of those dark forces, only to be purified and sent away through the power of fire.

By burning away evil and inviting new blessings, the Oniyo Festival turns fear into faith.

Shujō Oni-e (Oita) — The Oni of Blessing and Renewal

On the Kunisaki Peninsula in Oita Prefecture, the thousand-year-old Shujō Oni-e (“Oni Ritual”) is held at Buddhist temples.

This festival combines a New Year’s ceremony that prays for a rich harvest with the ancient tsuina ritual of chasing away evil spirits, and it has been passed down for centuries.

During the event, Oni called Ara-oni (Wild Demons) carry torches through temple grounds and nearby villages, sending out sparks to pray for good health and protection from illness.

Unlike the scary Oni of old legends, these figures are not evil but kind spirits of ancestors, returning to bless the community.

Villagers greet their visit with respect and joy, seeing them as messengers of good fortune and renewal.

Fear Transformed into Faith

These living traditions show that, in Japan, Oni are much more than symbols of fear.

They are seen as protectors of renewal—driving away bad luck and bringing happiness in return.

Through rituals of cleansing and blessing, Oni not only chase away evil but also share good fortune and spiritual peace with the people.

Rather than simply frightening others, Oni act as sacred guardians, guiding communities toward purification, prosperity, and harmony.

In this way, the image of the Oni shows that even fear, when faced with respect, can become a source of hope and renewal.

Oni in Art and Culture

Oni have also appeared in art, theater, and popular culture. In this section, let’s take a closer look at how Oni are portrayed in each of these areas.

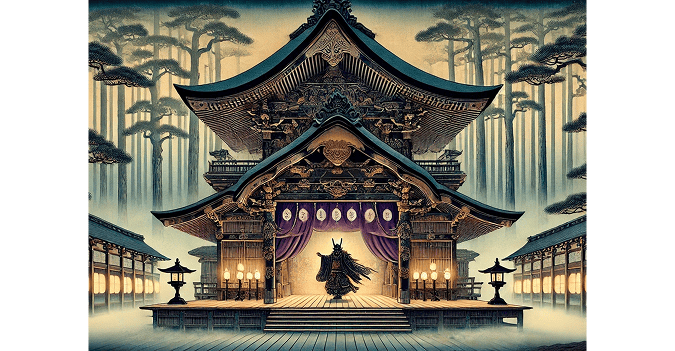

Traditional Arts: Ukiyo-e, Noh, and Kabuki

During the Edo period, ukiyo-e woodblock prints often showed Oni in famous stories such as Momotaro’s battle or Shuten-dōji’s defeat.

These colorful prints highlighted their fearsome strength and strange beauty, turning Oni into unforgettable cultural symbols.

On stage, both Noh and Kabuki theaters used striking Oni masks with sharp horns and fierce expressions. In Noh plays, Oni often represent extreme human emotions—like jealousy, rage, or sorrow—offering audiences a powerful lesson about the danger of losing control.

Modern Pop Culture: Anime, Manga, and Games

In modern Japan, Oni continue to appear widely—from anime and manga to video games.

Sometimes they are classic villains, but often they are reimagined as tragic or even sympathetic characters.

A well-known example is Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba, where Oni are shown as once-human beings cursed with monstrous power.

These Oni inspire both fear and compassion, showing how the idea of the demon has evolved into something more human and emotional.

A lighter example comes from the long-running video game series Momotaro Dentetsu.

Here, the character Binbōgami (the Poverty God)—with his horned, Oni-like appearance—brings bad luck to unlucky players.

Instead of a frightening monster, he becomes a funny symbol of misfortune, showing that Oni can also bring laughter and amusement in modern culture.

A small break — a little side note

Curious how Oni are imagined in modern Japan?

You might already know that Demon Slayer: Kimetsu no Yaiba has become a worldwide hit—not just in Japan, but across the globe.

This short video introduces several of the powerful Oni who appear as the story’s main enemies.

They are almost human—yet not quite—beautiful, eerie, and filled with deep tragedy.

Each one has a unique story, blending fear, emotion, and moral conflict in unforgettable ways.

If you’re interested, take a look and step into the world of Demon Slayer.

You’ll catch a glimpse of how modern Japan continues to reinterpret the image of the Oni in a way that is both haunting and profoundly human.

From traditional woodblock prints to modern anime, Oni remain timeless symbols of imagination.

While keeping their powerful presence, they have been reimagined in many ways—sometimes stirring deep emotions, and at other times appearing as friendly or humorous figures that people can easily relate to.

Conclusion: The Enduring Spirit of the Oni

From their ancient origins as invisible spirits to their fearsome roles in medieval legends, Oni have taken many shapes throughout Japanese history.

They punish the wicked in Buddhist hell, frighten villages in old folktales, appear as villains defeated by heroes, and sometimes even bring unexpected blessings.

But Oni are more than monsters of fear.

They are mirrors of the human heart, reflecting emotions such as greed, anger, and doubt—while also serving as protectors, teachers, and even playful figures in modern culture.

From sacred rituals and lively festivals to traditional art and popular anime, Oni continue to captivate both the Japanese people and audiences around the world.

Terrifying yet strangely endearing, the Oni remain one of Japan’s most powerful cultural symbols—reminding us of the thin line between fear and respect, and of the lessons hidden within our deepest imaginations.