Onmyoji: Japan’s Masters of Magic, Fate, and Balance

Have you ever wondered if magic could decide your future?

Long ago in Japan, there were mysterious men called Onmyoji. They read the stars, made calendars, and used spells to protect people from bad luck and evil spirits. Some said they could even talk with hidden spirits and control unseen powers. They were part advisor, part healer, and part magician. Emperors asked for their guidance, and ordinary people hoped for their protection.

But what kind of magic did they use? And what stories were told about them? Let’s step together into the world of the Onmyoji and explore their secrets.

Onmyodo: The Hidden System Behind the Onmyoji

Before we can understand the role of the Onmyoji, we need to take a closer look at the system they practiced—Onmyodo.

It was more than fortune-telling. Onmyodo was a uniquely Japanese way of understanding the world, guiding people in everything from choosing lucky days to protecting themselves from misfortune and keeping harmony with nature.

Origins and Development

So how did Onmyodo begin? The roots came from ancient China, where people studied the stars, tracked the seasons, and believed that balance in nature affected human life. These ideas reached Japan around the 5th to 6th centuries.

At first, Onmyodo focused on practical things like:

- making calendars,

- predicting the weather and natural disasters,

- choosing lucky days for important events.

In the beginning, these tasks were done by monks and scholars who could read Chinese texts. But as the Japanese court relied on this knowledge more and more, the role became official. By the late 7th century, specialists known as Onmyoji appeared to serve the imperial government.

During the Heian period (794–1185), Onmyodo grew into a full system with its own government office called the Onmyoryo (Bureau of Onmyo). From then on, Onmyoji were no longer just fortune-tellers—they became trusted advisors who influenced both everyday life and national affairs.

Core Concepts

So, what ideas made Onmyodo work?

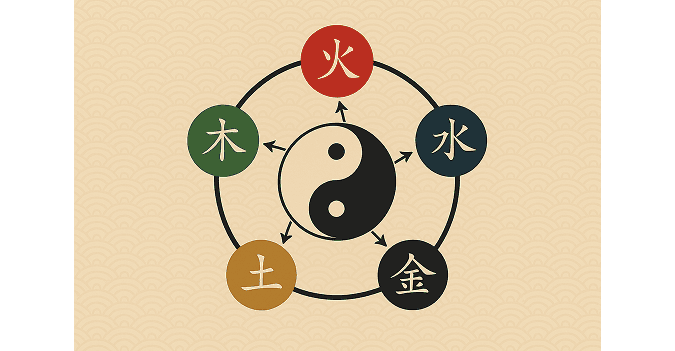

At its heart were two key beliefs that shaped how Onmyoji understood the world:

- Yin and Yang: the belief that everything has two sides—like light and dark, day and night, or even good and bad luck—and that balance keeps the world in harmony.

- The Five Elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. These were thought to shape the seasons, influence health, and connect people with the natural world.

Using these ideas, Onmyoji could help people with everyday questions such as:

- Which day is lucky for a wedding or a journey?

- Which direction is safe to build a house?

- How can I protect myself from sickness or misfortune?

To people back then, this wasn’t just superstition—it felt like trusted knowledge that guided both daily choices and life’s biggest moments.

Shinto, Buddhist, and Taoist Influence

Onmyodo didn’t grow on its own. Over time, it absorbed elements from Shinto, Buddhism, and Taoism, which gave it both practical power and deep spiritual meaning. Let’s take a closer look at how each tradition left its mark on Onmyodo.

- Shinto: Onmyodo absorbed ideas from Japan’s native faith, such as the worship of kami (spirits or gods) and purification rituals like misogi (water cleansing). By adopting these familiar practices, Onmyodo felt more like a natural part of everyday life, making it easier for people to connect with.

- Buddhism: From the 8th century onward, esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō) added mantras, rituals, and prayers for protection and healing. These gave Onmyoji powerful new tools against illness, misfortune, and evil spirits.

- Taoism: Onmyodo inherited techniques such as astrology to read the stars, divination based on directions, protective talismans (fuda) to guard against misfortune, and rituals to calm spirits or control unseen energy (qi). These practices added a strong sense of mystery and magical power to Onmyodo.

That mix of the practical and the mystical is what made Onmyodo so fascinating for the people of the time—and what still captures our imagination today.

The Role and Practices of Onmyoji

So what did the Onmyoji actually do?

They played important roles at both the imperial court and in ordinary people’s lives.

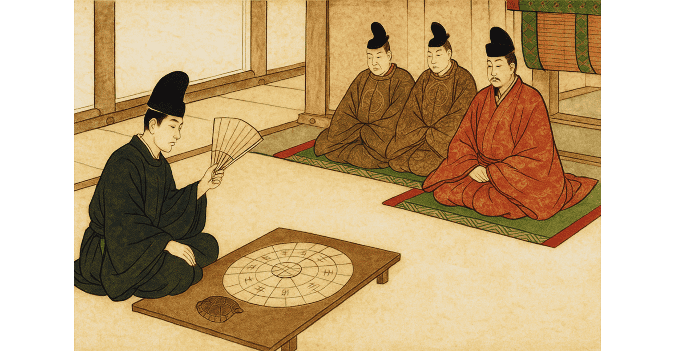

Duties at the Imperial Court

As specialists working in the imperial Onmyoryo (Bureau of Onmyo), Onmyoji mainly carried out tasks such as:

- creating calendars based on the movement of the stars,

- choosing lucky dates and directions for ceremonies or construction,

- performing state rituals to keep the nation safe from disasters,

- interpreting celestial signs like eclipses or comets.

In a world where the heavens were seen as signs of divine will, these roles were essential for the security of the country.

Services for the People

Onmyoji were not limited to the court. They also helped ordinary people by offering:

- Divination: predicting personal fortunes using methods like turtle shell reading or the I Ching.

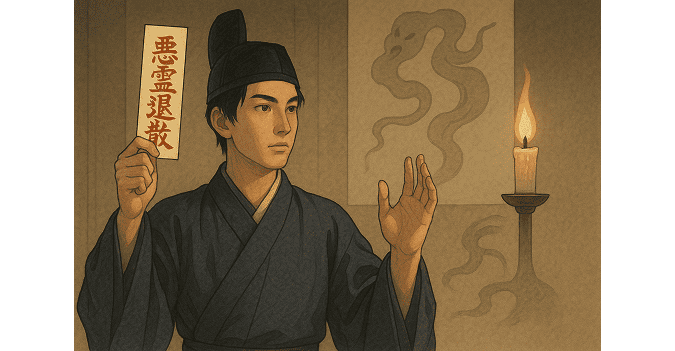

- Exorcisms and purification rituals: driving away evil spirits (akuryō) and cleansing polluted spaces.

- Protective charms and talismans (ofuda): giving families spiritual safety from illness or accidents.

- Healing prayers and spells: often blended with Buddhist or Taoist methods.

For many, the Onmyoji were trusted advisors who brought peace of mind in uncertain times.

Tools of the Trade

To carry out their work, Onmyoji used a range of special tools and symbols, such as:

- astrological charts and calendars based on yin-yang and the five elements,

- divination boards and turtle shells for fortune-telling,

- spirit-summoning scrolls that could call on mysterious beings like Shikigami,

- talismans and seals written with sacred scripts for protection.

To the people, their rituals looked both scientific and magical at the same time.

A Mix of Respect and Fear

Because of their wide-ranging powers, Onmyoji were both admired and feared. They could calm disasters and offer protection, but people also believed they might use their skills for curses or political intrigue.

This dual image made them figures of mystery—guardians of hidden knowledge that most people could only glimpse from the outside.

Famous Historical Onmyoji

In this section, let’s take a closer look at some of the most famous Onmyoji in Japanese history.

These figures are remembered not only for their skills, but also for the legends and stories that keep their names alive today.

Abe no Seimei (921–1005)

Perhaps the most legendary of all Onmyoji, Abe no Seimei served the imperial court during the Heian period. He was celebrated for his talent in astrology, divination, and exorcism, and his name later became almost synonymous with Onmyoji itself.

Stories tell of him summoning Shikigami, controlling spirits, and protecting the capital from curses and disasters. Countless tales made Abe no Seimei a legendary figure, and his name still echoes through Japanese history and folklore.

Kamo no Yasunori (917–977)

Another key figure was Kamo no Yasunori, a respected scholar and Onmyoji. He helped refine Japan’s official calendar system and advanced techniques of astrology. He also became the teacher of Abe no Seimei, passing on his knowledge and methods to the next generation.

The Kamo family, together with the Abe family, formed the core lineages of professional Onmyoji.

Ashiya Doman (active in folklore)

Unlike Seimei or Yasunori, the figure of Ashiya Doman is surrounded by legend. In folklore, he often appears as a rival to Abe no Seimei—a sorcerer who sometimes used his powers for selfish or darker purposes.

Whether or not he truly existed, his stories highlight the double-edged image of the Onmyoji: protectors of order, but also feared as potential wielders of dangerous magic.

These three figures—Seimei, Yasunori, and Doman—capture both the historical reality and the mythical aura of Onmyoji. Even today, their names spark the imagination, reminding us how Onmyoji stood at the crossroads of history and legend.

The Rise of Onmyoji: From Court Specialists to Political Powerhouses

Onmyoji first established themselves as specialists within the imperial court, but their power did not stop there. As time went on, they rose even further—becoming influential figures in politics and society.

Let’s explore how they made this remarkable journey from court experts to power players.

Expansion into Private and Political Life

By the mid-Heian period (10th–11th centuries), the power of the aristocracy was growing, and noble families began to rely on Onmyoji for private matters as well. Some hired them for secret rituals or even curses (jubaku) against rivals, while others sought their guidance for political strategy and family affairs.

In this way, Onmyoji became not only spiritual authorities but also influential players in court politics.

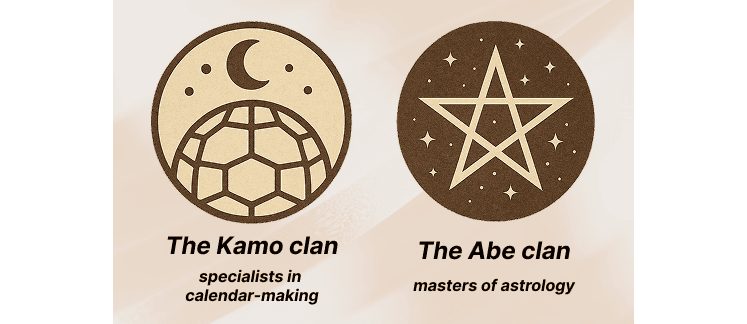

The Dominance of the Kamo and Abe Clans

During this same period, two families held near-total control over Onmyodo:

- the Kamo clan, specialists in calendar-making (rekidō),

- the Abe clan, masters of astrology (tenmondō).

Figures like Kamo no Yasunori, Kamo no Mitsuyoshi, and Abe no Seimei helped formalize Onmyodo into hereditary secret arts.

Through this monopoly of knowledge, their families secured lasting influence and elevated Onmyoji into charismatic leaders who stood at the center of both spiritual and political life.

Together, these developments marked the peak of Onmyoji power. They had become central players in Heian society—respected, feared, and deeply entrenched in the world of both politics and spirituality. This was the height of their influence—but as history shows, no power lasts forever.

The Decline of Onmyoji: Loss of Influence under Samurai Rule

As the Heian period came to an end, the role of the Onmyoji also reached a turning point. With the rise of the Kamakura period (1185–1333), real political authority shifted from the imperial court to the new samurai government (bakufu).

From this moment, the influence of the Onmyoji began to fade.

Shifts in Power and Influence

The new samurai rulers valued military strength and administration more than spiritual advisors. While Onmyoji still served aristocrats and even some shoguns, their role in national politics steadily declined.

Their influence became mostly confined to the highest ranks of nobility, while ordinary samurai and common people turned instead to new Buddhist sects—such as Pure Land and Zen—for spiritual guidance and support.

Decline of the Great Families

The powerful lineages that once controlled Onmyodo also weakened:

- the Kamo clan lost its influence and eventually disappeared,

- the Abe clan transformed into the Tsuchimikado family, keeping their hereditary knowledge but limiting their reach.

Without their former monopoly, the prestige of the Onmyoji diminished.

By the Edo period (1603–1868), Onmyoji survived mainly as ceremonial figures in the imperial court.

Once powerful advisors at the center of politics and society, the Onmyoji had lost much of their former presence—fading into shadows and becoming figures on the verge of slipping into the pages of history. Yet their final chapter was still to come.

The End of Onmyoji as an Official Institution

By the Meiji Restoration (1868), Japan was entering a new era of modernization. The government sought to replace old systems with modern science and Western knowledge—and in this transformation, the role of the Onmyoji finally came to an end.

Abolition of the Onmyoryo

In 1870 (Meiji 3), the government officially abolished the Onmyoryo (Bureau of Onmyo).

Its duties—such as calendars, astronomy, and astrology—were transferred to modern institutions like the Naval Hydrographic Office (the navy’s office for mapping and astronomy) and the Government Astronomical Observatory.

Ban on the Onmyoji Profession

That same year, the government also declared the profession of Onmyoji illegal under the Tensha Kinshirei (Ban on Heavenly Agencies).

- Onmyoji lost all official status and privileges,

- both public and private Onmyodo rituals were prohibited,

- and the Tsuchimikado family, who had long held hereditary rights, were stripped of their authority.

Discontinuation of Imperial Rituals

Ancient ceremonies once vital to imperial succession were also abolished.

Among them were rituals where Onmyoji used celestial signs and calendar knowledge to confirm the emperor’s authority as granted by the heavens. These rites symbolized the passing down of cosmic order from one ruler to the next.

With the reforms of the Meiji government, even these sacred traditions were discontinued—what had once been central to the nation’s spiritual and political fabric was now considered outdated in the age of modernization.

With these reforms, the Onmyoji disappeared as an official institution.

From guardians of the state to echoes of the past, their thousand-year role in Japanese history had finally closed.

Modern Influence and Legacy

The Onmyoji may no longer exist, but their history and legends still shape Japan today.

In this section, let’s explore how traces of the Onmyoji can still be found—in shrines, folk beliefs, and even popular culture—keeping their mysterious image alive in the modern world.

Shrines and Traditional Rituals

There are still shrines in Japan closely connected to the legacy of the Onmyoji.

These sites keep the memory of Onmyodo alive through rituals, legends, and symbols that connect the past with the present.

-

Seimei Shrine (晴明神社, Kyoto): Dedicated to the legendary Abe no Seimei, this shrine is one of the most famous places linked to Onmyodo. Visitors come to pray for protection, good fortune, and the warding off of bad luck.

-

Tenshagū (天社宮, Fukui Prefecture): A sacred shrine where prayers are offered to drive away misfortune and invite good fortune, based on the ancient teachings of Onmyodo. It is dedicated to Taizan Fukun, a deity of destiny and longevity.

Only the Tsuchimikado family—descendants of the Abe clan—were historically permitted to enshrine this deity, making Tenshagū unique as the only shrine of its kind in Japan.

Folk Beliefs and Fortune-Telling

Many elements of modern Japanese fortune-telling trace their roots back to Onmyodo.

For example:

- Kyūsei (nine-star astrology): still used to check luck and compatibility

- Rokuyō (six-day cycle): the familiar calendar marks like Taian (lucky) or Butsumetsu (unlucky)

- directional divination (katatagae): which advised people to avoid unlucky directions when traveling or moving house

- Fūsui (Feng Shui): originally from China, still used in Japan to judge the luck of land, houses, and directions.

Note: Historically, during the Heian period (794–1185), Feng Shui also influenced city planning in Japan—for example, the layout of Kyoto, then known as Heian-kyō.

These systems show how old cosmological ideas from Onmyodo were adapted into popular fortune practices that remain part of everyday life in Japan today.

Popular Culture

The image of the Onmyoji remains strong in Japanese pop culture:

- Novels and Films: The Onmyoji series by Baku Yumemakura, adapted into movies starring Mansai Nomura as Abe no Seimei.

A small break — a little side note

Ever wondered what the legendary rivalry between Abe no Seimei and his famous foe Ashiya Doman looked like?

Now you can see their epic story brought to life in this brand-new anime adaptation of Baku Yumemakura’s Onmyoji.

Heian-era magic, mysterious spells, and dramatic confrontations await!

Why not experience the spellbinding world of Onmyoji through anime—and discover why these timeless legends still fascinate people today?

First, take a peek at the trailer and step into this mystical world!

-

Anime and Manga: Titles like Tokyo Ravens and Nura: Rise of the Yokai Clan feature Onmyoji as key characters.

Curious readers can check out the official sites (Japanese):

-

Video Games: The hit mobile game Onmyoji by NetEase reimagines Heian-era magic in a modern fantasy RPG setting.

Curious readers can check out the official site (Japanese):

Through these works, the Onmyoji have become global cultural icons, inspiring audiences far beyond Japan.

The mysterious aura of the Onmyoji continues to captivate people even today. Their legends remind us that mystery can be just as powerful as history—and they still invite us to step into unseen worlds full of wonder and imagination.

Conclusion: The Enduring Mystery of Onmyoji

For over a thousand years, the Onmyoji shaped Japan’s spiritual and cultural landscape—guiding emperors, protecting communities, and interpreting the hidden rhythms of the universe. They stood at the crossroads of politics and belief, respected for their knowledge yet feared for their mysterious powers.

Though their role as official advisors ended long ago, the spirit of the Onmyoji never truly disappeared. It lingers in shrines, in fortune-telling traditions, and in the stories retold through novels, films, and games.

The mysterious aura of the Onmyoji continues to fascinate people even today. Their legends remind us that mystery can be just as powerful as history—and they still invite us to step into unseen worlds full of wonder and imagination.