The Three Sacred Treasures of Japan: From Myth to Modern Tradition

A mirror that captures the light of a goddess.

A sword born from a dragon’s tail.

A jewel shining with the spirit of heaven.

These are Japan’s Three Sacred Treasures — the mirror, sword, and jewel.

For more than a thousand years, they have fascinated people — not for what they look like, but for the mystery that surrounds them.

Wrapped in legend, they stand as timeless symbols linking Japan’s ancient myths with the spirit of the present day.

What stories do these treasures tell in Japanese mythology?

And how are they still connected to modern Japan?

Let’s begin a journey to uncover the secrets behind these treasures — to explore their legends, meanings, and the gentle magic that still shines at the heart of Japan’s culture.

What Are the Three Sacred Treasures?

Let’s begin with the basics of Japan’s Three Sacred Treasures.

What do these sacred objects mean, and what symbols do they carry within them?

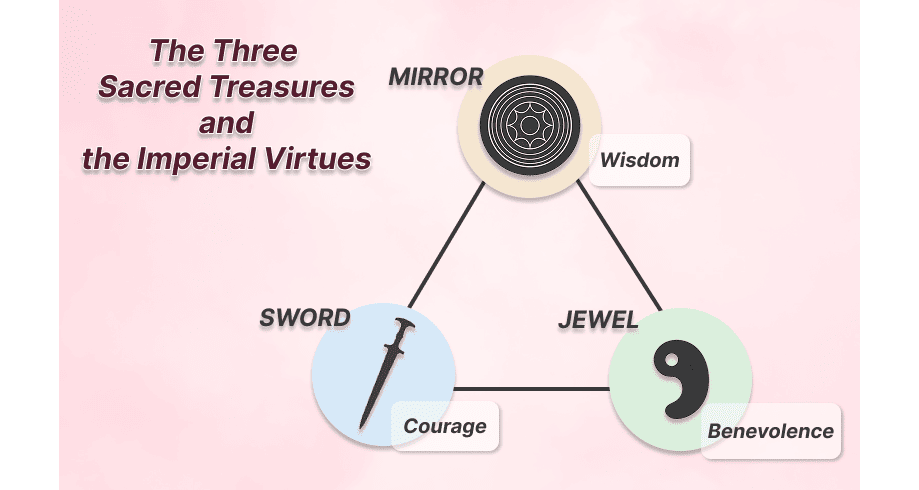

These three legendary items are known in Japanese as Sanshu no Jingi — literally, “the three sacred gifts of the gods.”

They are:

- Yata no Kagami — The Mirror

- Kusanagi no Tsurugi — The Sword

- Yasakani no Magatama — The Jewel

Each treasure carries its own sacred meaning, reflecting the virtues that have guided Japan’s spirit for centuries:

| Treasure | Symbolizes | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Mirror (Yata no Kagami) | Wisdom & Honesty | A true leader should see the world clearly and reflect truth. |

| Sword (Kusanagi no Tsurugi) | Courage & Strength | The bravery to protect others and face hardship. |

| Jewel (Yasakani no Magatama) | Benevolence & Harmony | A gentle heart that brings people together in peace. |

Together, these three form a perfect balance of mind, body, and spirit — a harmony of virtues that shines at the very heart of Japanese tradition.

How the Treasures Passed from the Gods to the Emperors

Now that we know the basics of the Three Sacred Treasures, let’s explore how their story intertwines with the ancient myths of Japan.

From the Myths of Heaven

The story of the Three Sacred Treasures dates back thousands of years.

According to legend, the treasures were given by the sun goddess Amaterasu to her grandson Ninigi-no-Mikoto when he descended from the heavens — an event known as Tenson Kōrin, the Descent of the Heavenly Grandson.

They were meant to guide him with wisdom, strength, and kindness — the virtues needed to bring peace to the human world.

Symbols of Divine Succession

After Amaterasu entrusted the Three Sacred Treasures to her heavenly descendant, how did their journey continue through the ages?

Over time, these treasures came to symbolize the divine link between the gods of Japanese mythology and Japan’s emperors, who are traditionally believed to be direct descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu herself.

Throughout history, they have been carefully protected and passed down from one emperor to the next — a tradition that still continues quietly today, uniting myth and monarchy through centuries of change.

The Three Sacred Treasures, rooted in ancient legend yet believed to exist even now, are among Japan’s most sacred symbols — linking heaven and earth, past and present, in an unbroken story of divine heritage.

The Connection with Japanese Mythology

Each of the Three Sacred Treasures carries its own story.

In Japan’s oldest chronicles — the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki — the treasures are described as sacred gifts bestowed upon humankind by the gods.

Let’s take a closer look at the legends behind each treasure, and discover how their spirit still lives on in Japan today.

Yata no Kagami — The Mirror

Long ago, when the sun goddess Amaterasu hid herself inside a cave, the world was plunged into darkness.

To lure her out, the gods created a shining mirror — the Yata no Kagami — and placed it at the entrance of the cave (Amano-Iwato Legend).

Mistaking her own radiant reflection for another divine being, Amaterasu grew curious and stepped out from the cave — and in that moment, light returned to the world.

Since then, the mirror has symbolized truth and clarity, the power to reflect what is pure and reveal what is hidden.

In the real world:

Yata no Kagami is believed to be a large copper mirror, possibly between 40–80 cm in diameter.

The original is enshrined at the sacred Ise Grand Shrine, while a replica is said to rest within the Imperial Palace.

Neither is ever shown to the public, preserving its sacred mystery.

Kusanagi no Tsurugi — The Sword

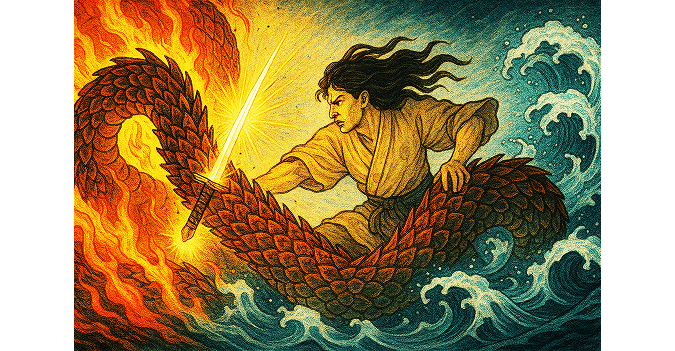

The Kusanagi no Tsurugi, or “Grass-Cutting Sword,” has its origins in one of Japan’s most dramatic myths.

The storm god Susanoo defeated the monstrous eight-headed serpent Yamata-no-Orochi.

Inside the creature’s tail, he discovered a gleaming blade — first called Ame-no-Murakumo-no-Tsurugi, “The Sword of the Gathering Clouds.”

Later, when a hero used it to cut through burning grass and escape death, it earned its new name: Kusanagi, “The Grass-Cutter.”

In the real world:

The sword is said to be about 85 cm long, a straight, double-edged blade that may have been forged of bronze.

Its true form remains hidden within the sanctum of Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya, central Japan, unseen by all but the highest priests.

Yasakani no Magatama — The Jewel

The Yasakani no Magatama is a beautifully curved jewel made from jade or agate — a sacred ornament that dates back to Japan’s earliest myths.

In legend, it was hung upon a sacred tree beside the mirror to help draw Amaterasu from her cave, and later exchanged in a divine oath between her and Susanoo.

Though quiet in its presence, the magatama has long been cherished as a symbol of the unseen spirit that connects heaven and earth.

In the real world:

The jewel is believed to be strung with other beads, possibly forming a necklace more than 140 cm long.

Its color is described in old texts as reddish-green or bluish jade, glowing softly in the imagination of those who have never seen it.

Like the other treasures, it remains unseen — kept within the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, protected and revered as a living symbol of peace.

The Role of the Three Treasures

Bestowed from the heavens upon the human world, the Three Sacred Treasures have followed a long and mysterious path through history.

How did these divine gifts shape Japan’s history, and what role do they continue to play today?

Let’s explore their story more deeply.

Echoes from Ancient Times

Long before written history began, objects resembling the mirror, sword, and magatama jewel already existed in Japan.

Archaeologists have unearthed these items from Yayoi and Kofun period burial sites — including the Yoshitake-Takagi Site in Fukuoka and the Shichigase Site in Saga.

In those ancient times, mirrors symbolized light and divine power, swords represented protection and strength, and magatama beads carried spiritual meaning.

Powerful regional leaders often owned or buried these items as symbols of authority and sacred connection.

These discoveries suggest that the origins of the Three Sacred Treasures reach back long before the rise of Japan’s earliest kingdoms.

From Ritual Objects to Sacred Regalia

As Japan’s spiritual beliefs evolved, these three items were woven into the emerging Shinto faith.

By the 6th and 7th centuries, when Shinto began to take on an organized form, the mirror, sword, and jewel had become symbols of divine favor — not only tools of ritual, but representations of purity, courage, and harmony.

When the myths of Amaterasu and her heavenly descendants were later recorded in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, these objects were identified as the Three Sacred Treasures — the gifts of the gods that linked heaven and earth.

This marked the moment when ancient symbols of power became sacred emblems of divine origin.

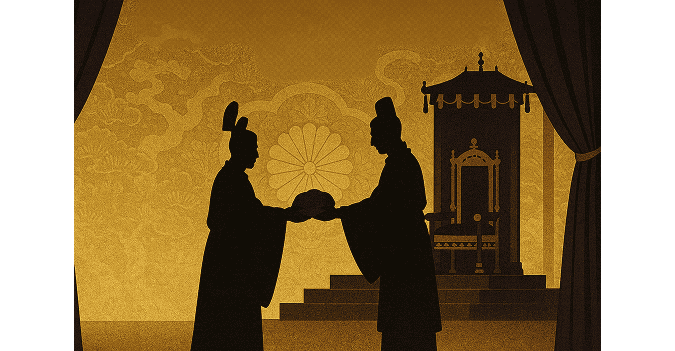

The First Recorded Inheritance

As Japan’s imperial system matured, the Three Sacred Treasures came to represent not only faith, but also imperial authority.

The Shoku Nihongi records that in the year 690, Empress Jitō received the mirror and sword during her enthronement ceremony — the first official record of the regalia being used in imperial succession.

From that time onward, the treasures were inseparable from the idea of legitimate rule.

They embodied both political continuity and the spiritual link between the gods and Japan’s emperors — a bond that remains deeply respected even today.

Note: The Yasakani no Magatama (the curved jewel) came to be formally recognized as part of the Three Sacred Treasures and incorporated into imperial rituals during the Heian period (794–1185).

Codified Meanings in Imperial Tradition

As centuries passed, their meaning deepened under the influence of Chinese Confucian philosophy, which emphasized the ruler’s moral duty to lead with virtue.

Each treasure came to represent an ideal quality of leadership:

| Treasure | Virtue | Ideal |

|---|---|---|

| Mirror | Wisdom | To see clearly and act with honesty. |

| Sword | Courage | To face challenges with strength and justice. |

| Jewel | Benevolence | To rule with compassion and harmony. |

Through these virtues, the treasures became more than symbols of divine descent — they evolved into a moral compass for Japan’s emperors, guiding how a ruler should lead the nation.

Imperial Succession Today

The sacred role of the Three Treasures continues in modern times.

When a new emperor ascends the throne, the sword and jewel are ceremonially presented during the Ceremony for Inheriting the Imperial Regalia and Seals (Kenji-to-Shokei-no-gi).

This solemn rite represents not only the transfer of political authority, but also the continuation of the emperor’s spiritual duty to serve as a bridge between the divine and the people.

The most recent appearance of the Three Sacred Treasures took place on May 1, 2019, during the Ceremony for Inheriting the Imperial Regalia and Seals held at the Matsu-no-Ma Hall of the Imperial Palace.

On that day, the current emperor formally received the sacred treasures — a solemn event that reaffirmed a tradition unbroken for more than a thousand years.

Even today, the Three Sacred Treasures remain at the heart of Japan’s imperial tradition — quietly linking myth and monarchy, and reflecting the timeless virtues that continue to guide the nation.

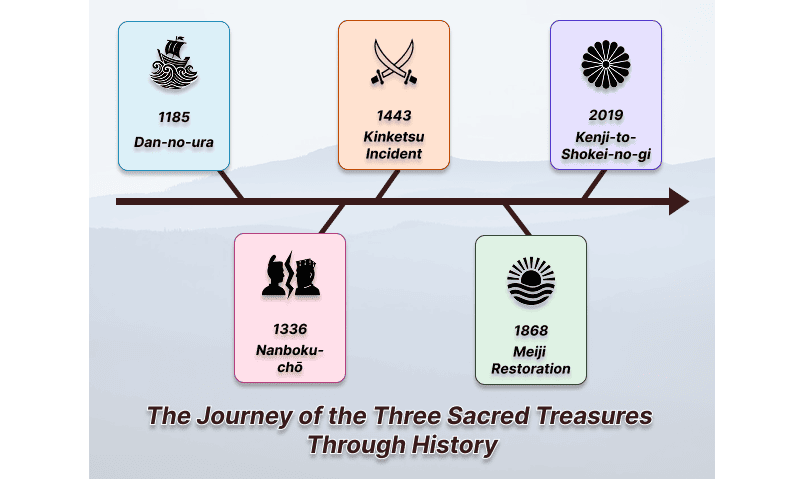

History of the Treasures

Did you know that over the course of more than a thousand years of Japanese history, the Three Sacred Treasures have faced moments of loss, danger, and uncertainty?

Through every upheaval, they have been carefully protected, restored, and passed down to each new emperor — preserving their place as enduring symbols of Japan’s imperial spirit.

Let’s look back at several key moments when the fate of the treasures hung in the balance.

The Battle of Dan-no-ura (1185)

At the end of the Genpei War, the child emperor Antoku fled with the Taira clan, carrying the sacred treasures with him.

When defeat became certain, the emperor’s grandmother leapt into the sea with the young emperor in her arms — taking the sacred sword, Kusanagi no Tsurugi, with them.

Some records claim the sword was later recovered by divers, while others believe a replica was made to replace the one lost to the depths.

Whatever the truth, the legend of the sunken sword has endured as one of the most haunting stories in Japanese history.

The Era of the Northern and Southern Courts (1336–1392)

Centuries later, Japan was divided between two rival imperial lines — each claiming to be the rightful ruler and each asserting possession of the true imperial regalia.

This long conflict, known as the Nanboku-chō period, turned the Three Sacred Treasures into powerful symbols of legitimacy.

Only the emperor who held them could be recognized as the true sovereign.

It was not until the Meiji period (1868–1912) that the question of which imperial line was truly legitimate was finally settled.

During this era, Emperor Meiji declared the Southern Court to be the rightful imperial line — a decision influenced in part by the belief that it had preserved the sacred regalia and upheld the spiritual authority of the throne throughout the conflict.

The Kinketsu Incident (1443)

During Japan’s Muromachi period (1336–1573), loyalists of the former Southern Court broke into the Imperial Palace in Kyoto and succeeded in stealing two of the sacred treasures — the sword and the jewel.

Known as the Kinketsu Incident, this shocking event deeply unsettled the imperial court.

Yet beyond the theft itself, it revealed how profoundly the Three Sacred Treasures were bound to the emperor’s authority.

To possess them was to hold the very legitimacy of the throne.

The sword was recovered the following day, while the jewel was kept by Southern Court supporters for more than ten years before finally being returned in 1457.

In the aftermath of this crisis, the protection of the regalia became even more stringent — a reflection of just how precious they had become to Japan’s imperial tradition.

From the crashing waves of Dan-no-ura to the court intrigues of medieval Kyoto, the Three Sacred Treasures have endured wars, thefts, and political divisions.

Looking back on these many trials, one can truly appreciate how remarkable it is that the treasures have been preserved and passed down to this very day — a legacy of devotion and resilience that still shines through Japan’s long history.

Why They Still Matter Today

We have traced the story of the Three Sacred Treasures — from myth and legend to history and tradition.

But what do they mean in modern Japan — and what significance do these ancient symbols still hold in a world so different from the one in which they were born?

A Bridge Between Myth and the Present

The Three Sacred Treasures stand at the crossroads of myth and history, linking the divine origins of Japan’s imperial line to the modern world.

Even though they remain hidden from sight, their unseen presence continues to embody a story — one of faith, tradition, and identity passed down unbroken for more than a thousand years.

Their inaccessibility only deepens their aura of mystery, reminding people that their value lies not in being touched or seen, but in what they represent — the timeless spirit of Japan itself.

In this way, the treasures remain both precious and irreplaceable, a quiet testament to the enduring bond between Japan’s past and its present.

Enduring Virtues for Modern Times

The Three Sacred Treasures are not only mysterious relics of the past — they also reflect the guiding ideals and moral compass of Japan itself.

As we have seen, the mirror teaches clarity and truth, the sword represents courage and justice, and the jewel embodies compassion and harmony.

What once served as virtues for the imperial family have since taken root as values deeply cherished by the Japanese people.

They are not loudly proclaimed, but quietly lived — in sincerity and honesty, in the courage to act with integrity, and in the compassion that seeks peace and understanding.

In this way, the Three Sacred Treasures shine not only as sacred symbols, but as reflections of the Japanese spirit — timeless, humble, and profoundly human.

Symbols of Continuity and Cultural Pride

Japan’s imperial line is recognized as the oldest continuing monarchy in the world, a living tradition that has endured for more than two millennia.

The Three Sacred Treasures stand as powerful evidence of that continuity — not merely symbols of imperial heritage, but of a nation that has preserved its identity through countless generations.

For the Japanese people, they embody a quiet sense of pride and belonging, while to the world, they represent a rare example of an ancient tradition that still thrives in the modern age.

In this way, the Three Sacred Treasures are more than symbols of Japan’s imperial legacy.

They offer a rare glimpse — for both the Japanese people and the world — of how ancient history continues to live and evolve in the present day.

Through them, one can still witness a living tradition where myth, faith, and culture are not relics of the past, but part of Japan’s ongoing story.

Across the ages, the Three Sacred Treasures continue to unite Japan’s mythology and history, to embody the virtues cherished by its people, and to quietly share their presence with the world.

Guarded and revered since ancient times, they will remain protected for as long as Japan itself endures.

And we, too, live within that same continuum — witnesses to the timeless story of the treasures that continue to shape Japan’s soul.

Conclusion: More Than Just Hidden Relics

The Three Sacred Treasures — the mirror, the sword, and the jewel — are far more than ancient objects locked away from view.

They are living symbols of Japan’s spirit, carrying within them over a thousand years of myth, history, and faith.

From their divine origins in the age of the gods to their quiet presence in modern imperial tradition, they have continued to connect heaven and earth, past and present, through an unbroken line of reverence and belief.

Though few will ever see them, their true power does not lie in their form, but in what they represent — the enduring virtues of wisdom, courage, and compassion that have shaped Japan’s heart.

The Three Sacred Treasures remain — silent, unseen, yet ever alive — guiding Japan with the same quiet strength that has endured since the dawn of its history.