Gagaku: Japan’s Timeless Art of Sound, Ritual, and Grace

A gentle shimmer. A breath of stillness. Then — sound flowing like a breeze from another world.

This is Gagaku — the oldest surviving music of Japan, and one of the longest-lasting musical traditions on Earth.

Its tones drift slowly, softly, and with a floating sense of space, as if they were resonating directly from nature itself.

What creates this mysterious sound and the unique feeling it inspires?

Let’s step into the world of Gagaku together.

From its ancient origins to its place in Japan today, and the instruments that bring its celestial music to life, we invite you to explore this timeless tradition with us.

What Is Gagaku?

To begin our journey, let’s start with a gentle overview of what Gagaku is.

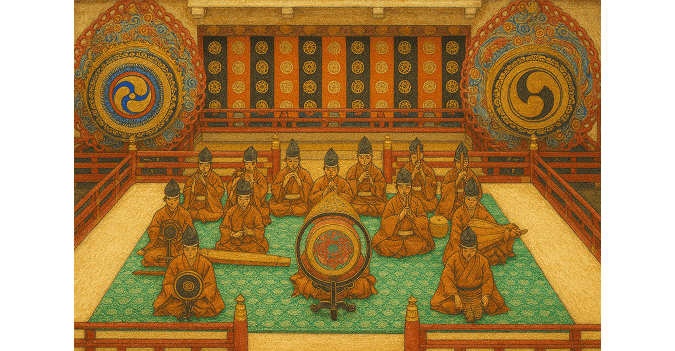

Gagaku is one of Japan’s classical performing arts, often described as the “world’s oldest orchestra.”

It is not a style that appeared suddenly or was created by a single person.

Instead, it evolved gradually over centuries.

Rooted in Japan’s ancient ritual music and dance, Gagaku also draws from musical and theatrical traditions that once came from China and the Korean peninsula.

Over roughly four hundred years, these influences blended and matured into a highly refined art form.

Gagaku’s Main Traditional Forms

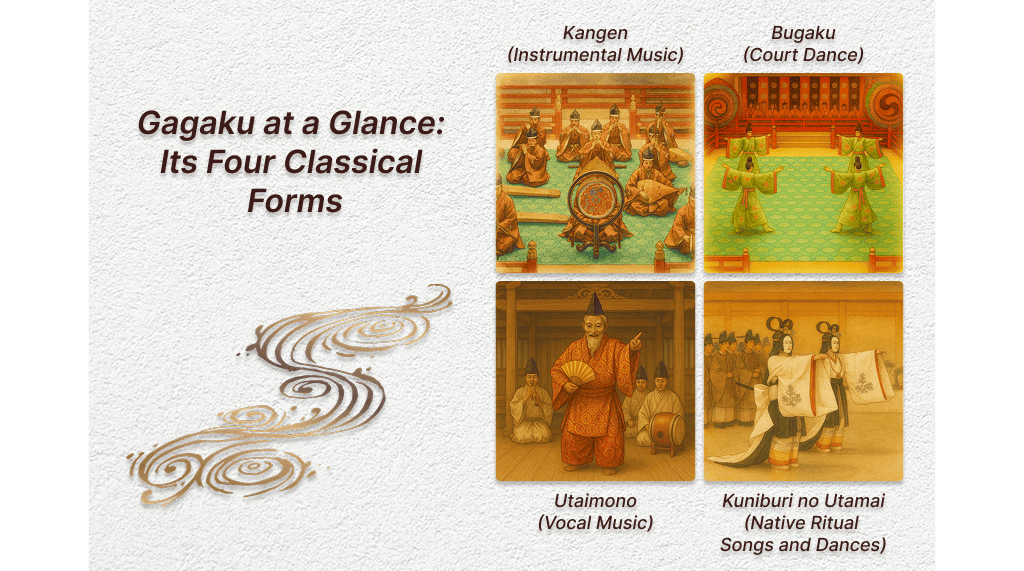

Today, Gagaku is typically divided into four major forms.

Let’s explore each one together.

1. Kangen — Instrumental Music

Performed with ancient instruments such as the shō (mouth organ), hichiriki (double-reed pipe), and ryūteki (bamboo flute).

Its sound is serene, floating, and almost otherworldly—perfect for creating a timeless sense of space.

2. Bugaku — Court Dance

Graceful, symbolic dances accompanied by Gagaku music.

Dancers wear colorful robes and masks, moving slowly and precisely to portray myths, historical stories, and legendary figures.

3. Utaimono — Vocal Music

Poetic vocal pieces such as saibara and rōei.

These songs celebrate nature, love, and spirituality, blending classical poetry with elegant melodies.

4. Kuniburi no Utamai — Native Ritual Songs and Dances

A uniquely Japanese tradition that developed before foreign influences arrived.

Rooted in ancient Shinto rituals, it expresses indigenous spirituality through solemn chanting and ceremonial movement.

The Formation of Gagaku: From Ancient Roots to Classical Completion

Gagaku was slowly shaped over roughly four centuries, and its beginnings stretch back more than 1,300 years into Japan’s past.

How did such a refined art form take shape over such a long span of time?

In this section, we’ll trace the history of Gagaku step by step — from its ancient roots to the point where it became the classical art form we recognize today.

Before Continental Influences (Pre–5th Century)

Long before music from China or the Korean peninsula arrived, the Japanese archipelago already had its own unique forms of song and dance.

These early traditions were performed during religious rituals, seasonal celebrations, and important communal or clan gatherings — marking significant moments in the life of each community.

At that time, every region and clan preserved its own style of performance, passing down songs and dances that reflected their local beliefs, customs, and cultural identity.

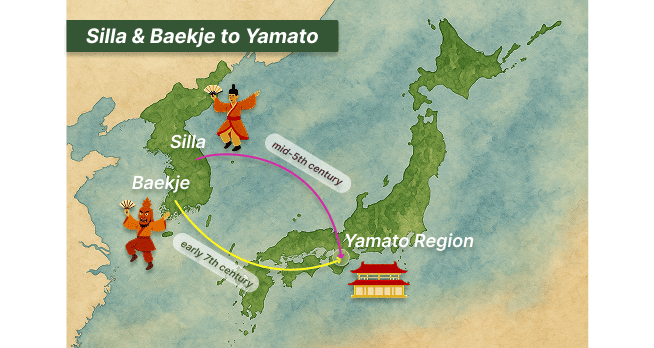

Ancient Origins (5th–7th Century)

By the 5th century, cultural exchange between Japan and the Korean peninsula had become increasingly active.

According to the Nihon Shoki, by the mid-5th century many musicians from Silla were already traveling to Japan to perform songs and dances.

In the 6th century, additional records describe musicians from Baekje who served at the Japanese court on a regular, rotating basis.

In the early 7th century, a new form of masked drama called Gigaku was introduced to Japan by a Baekje performer named Mimashi.

Gigaku would later be performed at major Buddhist ceremonies, including the eye-opening ritual of Tōdaiji.

These performances formed the earliest layer of continental artistic influence that would later contribute to the development of Japanese Gagaku.

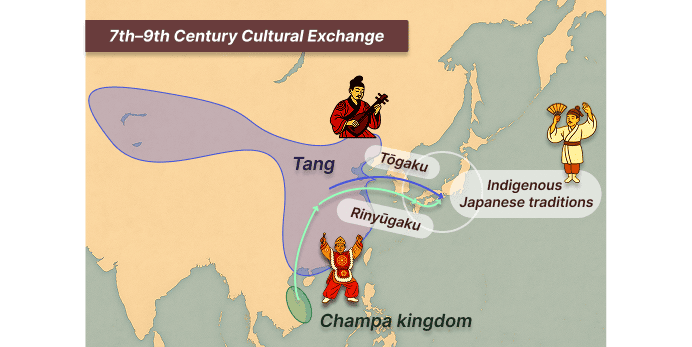

Formation of Gagaku (Asuka to Early Heian Period, 7th–9th Century)

From the 7th century onward, Japan experienced a major wave of cultural exchange.

During this era, several important musical traditions entered the country and blended with native performing arts, forming the foundation of Gagaku.

- Tōgaku (唐楽) — Elegant court music introduced from the Tang dynasty in China.

- Rinyūgaku (林邑楽) — Lively music and dance brought by performers from the Champa kingdom in what is now central Vietnam.

- Indigenous Japanese traditions — Ancient songs and dances from across Japan were brought to the capital and refined into court performance.

To organize these diverse influences, the court established the Gagaku Bureau (Gagakuryō) in 701.

Through this system, foreign and native arts were harmonized and shaped into a uniquely Japanese classical tradition.

The Journey of Gagaku After Its Classical Completion

Once Gagaku had taken its classical form, the tradition continued to evolve through eras of prosperity, hardship, and renewal.

Let’s follow how it survived and transformed from the Heian period to the present day.

Golden Age of Gagaku (Heian Period, 9th–12th Century)

During the Heian period, Gagaku flourished as court culture reached its artistic peak.

Several key developments shaped this golden age:

-

Establishment of permanent gakusho (楽所)

Dedicated music halls were created and gradually took over many functions of the Gagaku Bureau. -

Emergence of hereditary gakke families (楽家)

Musical roles became organized into family lineages, ensuring stable transmission across generations. -

Rise of aristocratic musical culture

Nobles held private salons and musical gatherings, expanding Gagaku beyond formal state rituals. -

Creation of utaimono (謡物)

New lyrical vocal genres emerged, reflecting the refined aesthetics of Heian aristocratic life.

Through these developments, Gagaku matured into the elegant and polished court art that would define Japan’s classical musical heritage for centuries to come.

Survival Through Turbulent Times (Medieval Japan, 12th–16th Century)

As political power shifted from the imperial court to the samurai class, the world of Gagaku underwent major changes.

During this time, three major shifts reshaped the path of Gagaku:

1. Spread Beyond the Court — The Samurai as New Patrons

Following aristocratic customs, samurai families learned and supported Gagaku.

Because of their patronage, Gagaku spread widely to shrines, temples, and regional festivals across Japan.

2. Crisis During the Warring States Period

As warfare engulfed the country, Kyoto — the center of Gagaku — was devastated.

Court life collapsed, musicians were scattered, and many ancient pieces and traditions were on the brink of being lost.

3. Preservation and Revival by the Gakke Families

The hereditary gakke families of Osaka and Nara safeguarded the tradition throughout the turmoil.

They preserved:

- centuries-old musical techniques

- valuable gakusho manuscripts documenting ancient repertoires

When peace returned in the late 16th century, these musicians were summoned back to the court.

By combining their preserved knowledge, they rebuilt the tradition, leading to the establishment of the Sanpō Gakusho (Three Court Music Offices) — Kyoto, Nara, and Osaka jointly supporting imperial ceremonies.

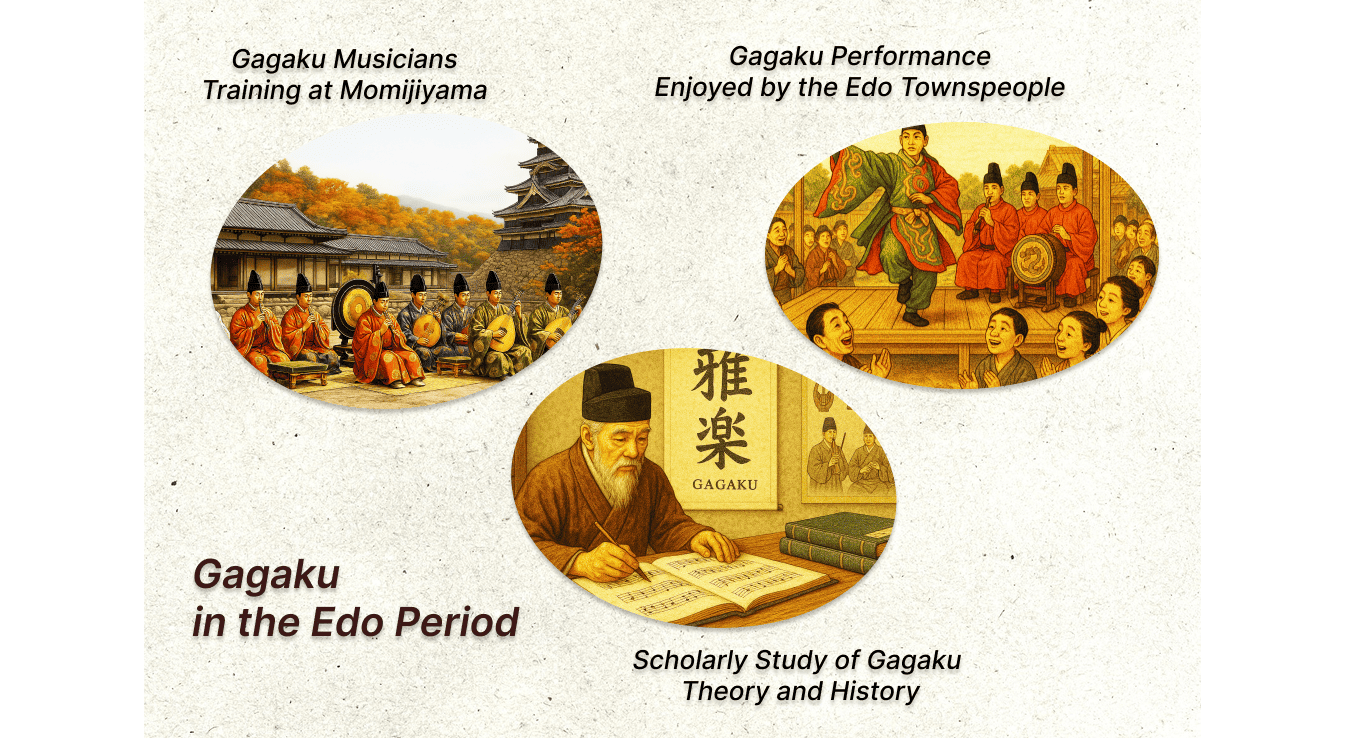

Revival and Reorganization (Edo Period, 17th–19th Century)

During the Edo period, Gagaku entered a renewed era of growth and stability.

Its development in this time can be summarized through several key points:

- Formation of a combined ensemble of nearly one hundred musicians, active both at Edo Castle’s Momijiyama and in the Kyoto–Nara–Osaka region

- Establishment of the Sanpō Kyūdai examinations to maintain high artistic standards

- Active advancement of scholarship, including research into Gagaku’s history, theory, and ancient manuscripts

- Expansion of Gagaku’s influence among townspeople and farming communities, spreading far beyond the aristocratic world

Thanks to this broad support and renewed cultural interest, Gagaku achieved its greatest flourishing since the Heian period.

This momentum also made it possible to revive lost compositions and restore long-discontinued ceremonial traditions, bringing back much of the tradition’s ancient richness.

Gagaku in the Modern Era (Meiji to Present, 19th–21st Century)

From the Meiji period onward, Gagaku entered a new chapter of reform and preservation that shaped its modern identity.

Here are the key milestones that define its development:

-

Unification of the tradition (Meiji era)

– A new Gagaku Department brought together musicians from Kyoto, Nara, Osaka, and Edo.

– Notation and performance techniques were standardized into the Meiji Standard Edition. -

Training Opens to the Public

– For the first time, people outside hereditary families were allowed to study Gagaku. -

Postwar Preservation System

– The Imperial Household Agency’s Music Department became the central institution for preservation and transmission.

– Gagaku and its master musicians were recognized as Important Intangible Cultural Heritage. -

Global Recognition

– In 2009, Gagaku was listed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

Today, Gagaku continues to thrive—performed at imperial ceremonies, Shinto rituals, academic institutions, and on concert stages across Japan and around the world.

The Distinctive Beauty of Gagaku

Have you ever felt that quiet, almost spiritual mood when listening to Gagaku?

To many Western listeners — whether they are used to the emotional drive of modern pop music or the structured harmony of classical music — Gagaku can feel mysterious and unfamiliar.

In this section, we explore what gives Gagaku its distinctive atmosphere and why its sound evokes such a unique impression.

A Music of Space — The Power of Ma (間)

Gagaku treats silence, stillness, and the spaces between sounds as essential musical elements.

Rather than sharply defined phrases, its musical lines unfold softly and gradually.

This can be heard in several characteristic features:

- Melodies that develop slowly over time

- Tones that drift and linger in the air

- Silence (ma) intentionally used as part of the expression

Unlike Western music — which often builds toward a climax — Gagaku creates a floating sense of time, gently drawing the listener into a meditative state.

This unique relationship with space and quietness forms one of the most profound beauties of Gagaku.

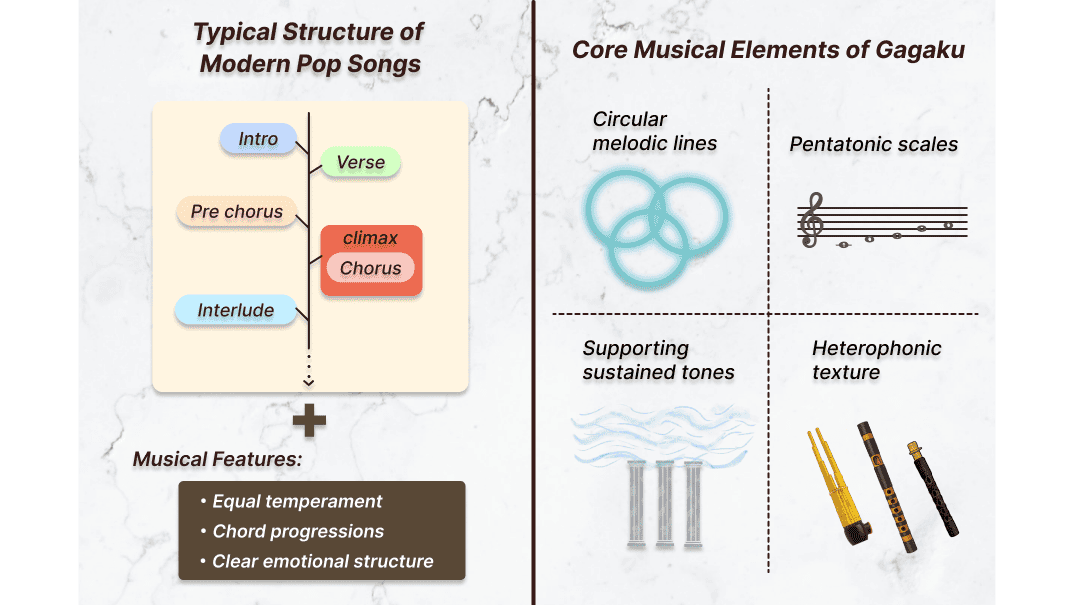

A Different Sense of Melody and Harmony

In Western music — whether classical or pop — melodies typically follow equal temperament, chord progressions, and a clear emotional structure. Songs often move from intro to chorus to climax, creating a sense of forward momentum.

Gagaku, however, follows a very different musical logic. Its melodic and harmonic world can be understood through the following qualities:

- Circular, decorative melodies rather than linear lines

- Five-note pentatonic scales instead of seven-note systems

- Stable “tone pillars” that anchor the sound without forming chords

- Multiple instruments performing the same melody with subtle variations

To unfamiliar ears, Gagaku may feel as though it lacks direction.

But this continuity is intentional — the music values an unbroken flow, allowing listeners to drift within its timeless atmosphere.

Ritual Pace Instead of Dramatic Tempo

In Western traditions, tempo often reflects human emotions: fast for excitement, slow for calm, and shifting tempos for dramatic effect.

Gagaku operates differently.

It respects the tempo of ritual and the rhythms of nature, rather than human feeling.

Its pacing can be understood through the following characteristics:

- Calm and steady throughout

- A dignified, solemn atmosphere

- Unhurried flow that feels like a single, continuous breath

Instead of dramatic contrasts or emotional peaks, Gagaku sustains a stable, ceremonial mood.

This reflects its origins not as entertainment, but as a way to maintain harmony between humans, nature, and the divine in ancient imperial and religious practices.

By comparing Gagaku with both modern Western pop and classical music, we begin to see that its beauty arises from entirely different musical values.

Gagaku embraces silence as sound, circular melodies without harmonic progression, and a ritual pace guided by the rhythms of nature.

Rather than leading the listener toward a dramatic climax, it opens a space where time slows, sound expands, and music becomes a gentle bridge between the human and the divine.

A small break — a little side note

Curious about how Gagaku sounds? Here’s a gentle first step.

Japan’s national anthem Kimigayo already carries a quiet, timeless beauty.

But when played with Gagaku instruments, its elegance deepens, becoming even more serene and ethereal.

Take a moment to listen — and let the mysterious, floating world of Gagaku wash over you.

The Instruments of Gagaku — Voices of an Ancient World

Gagaku’s sound feels like wind, light, and ancient breath woven together.

But what instruments create such an ethereal world of sound?

Let’s take a closer look at these remarkable instruments and the sounds that define Gagaku.

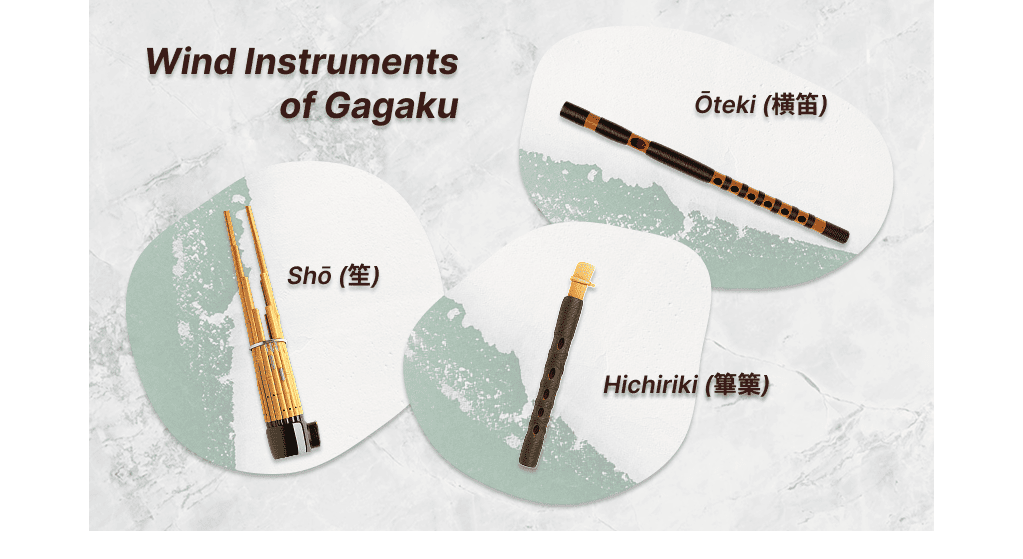

Wind Instruments — The Breath and Spirit of Gagaku

Wind instruments form the emotional and spiritual core of Gagaku.

Their tones drift, shimmer, and intertwine like air itself.

Shō (笙) — The Sound of Heaven

A mouth organ with seventeen slender bamboo pipes.

It produces soft, glowing harmonies and is the only Japanese instrument capable of playing true chords.

The shō sounds both when inhaling and exhaling, creating a continuous, seamless flow of tones.

Its shape resembles a mythical Chinese phoenix at rest, which is why it is also called hōshō (鳳笙).

Hichiriki (篳篥) — The Soul of Gagaku

A small, lacquered bamboo pipe with seven front holes and two on the back.

Using a double reed (similar to an oboe), it produces a bold, expressive, and emotional sound that often carries the main melody.

Despite its size, its voice is powerful and deeply distinctive — one of the most recognizable sounds in Gagaku.

Ōteki (横笛) — The Family of Transverse Flutes

Gagaku features several bamboo transverse flutes:

- Ryūteki (龍笛) — the standard flute of Tōgaku, also used in vocal pieces

- Komabue (高麗笛) — shorter and sharper in tone, used in Komagaku

- Kagurabue (神楽笛) — the longest, used primarily in Shintō ritual music

All share similar construction — six or seven finger holes — but vary in size, pitch, and character.

Together, they add brightness, motion, and expressive color to the ensemble.

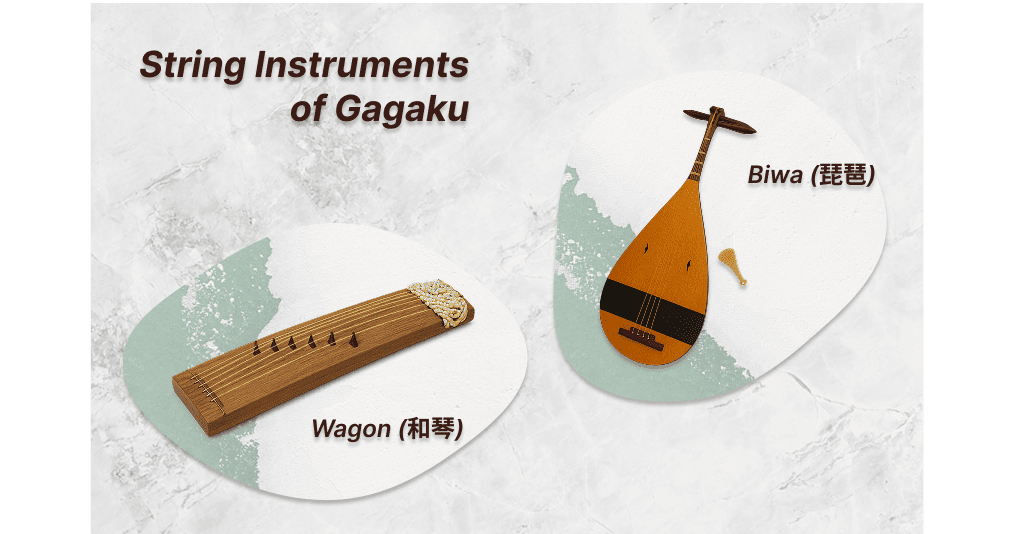

String Instruments — Ancient Voices Rooted in Tradition

These instruments connect directly to Japan’s earliest musical heritage.

Wagon (和琴) — An Ancient Voice

One of Japan’s oldest string instruments, mentioned even in the Kojiki.

Made from paulownia wood, it features six silk strings stretched over maple-branch bridges.

Played with a tortoiseshell plectrum, it produces a soft, gentle tone closely tied to ancient Shintō ritual music.

Biwa (琵琶) — The Lute of the Court

Also called gaku-biwa, it is the largest type of biwa used in Japan.

With its loquat-shaped wooden body and four silk strings, it adds rhythmic accents, chords, and percussive depth to Gagaku.

It supports both melody and rhythm, enriching the ensemble’s texture.

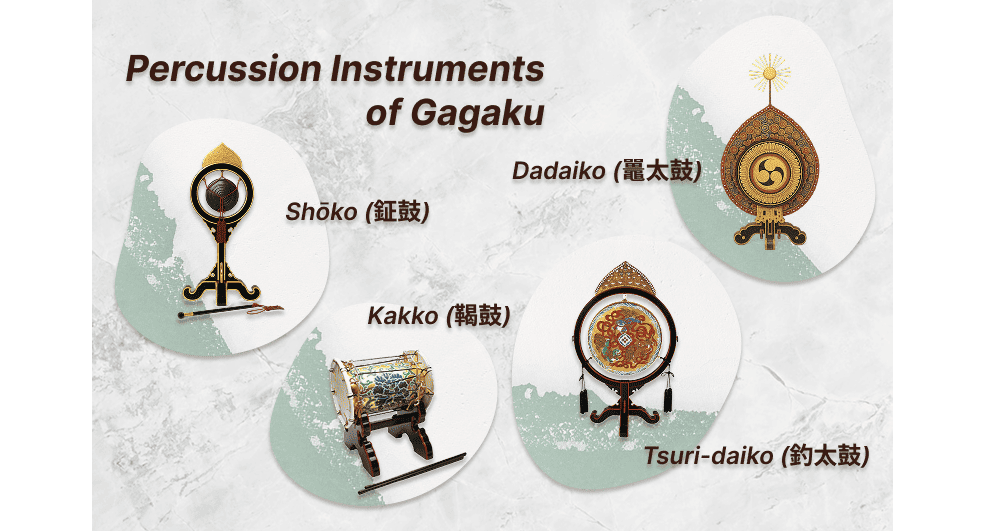

Percussion Instruments — The Pulse of Ceremony

Percussion provides structure, ritual pacing, and ceremonial grandeur.

Shōko (鉦鼓) — The Metal Heartbeat

The only metal instrument in the ensemble’s percussion family.

This shallow bronze gong is struck on the inside with a wooden mallet to mark structural points in the music.

Kakko (鞨鼓) — The Director of Tempo

A small, slightly bulging drum decorated with vivid colors.

Played with two thin sticks, the kakko guides tempo, signals transitions, and often acts as the conductor of the ensemble.

Taiko (太鼓) — The Foundation of Power

Gagaku uses two main types:

- Tsuri-daiko (釣太鼓) — suspended in a circular frame, used in kangen (instrumental) music

- Dadaiko (鼉太鼓) — a massive ceremonial drum used in bugaku dance, played with heavy mallets to create a deep, powerful presence

Together, these instruments do more than keep time — they create the ritual heartbeat of Gagaku, grounding its floating melodies in a timeless ceremonial pulse.

As a whole, these distinctive instruments — and the worlds of sound they create — form the unique tone and atmosphere that define the art of Gagaku.

Bugaku — The Ceremonial Dance of Gagaku

Bugaku is the dance performed together with Gagaku music — a union of sound and movement.

If you want to understand Bugaku more deeply, there are three key points to focus on: its two major lineages, its traditional categories of dance, and its system of codified movements.

In this section, we will explore these defining features of Bugaku.

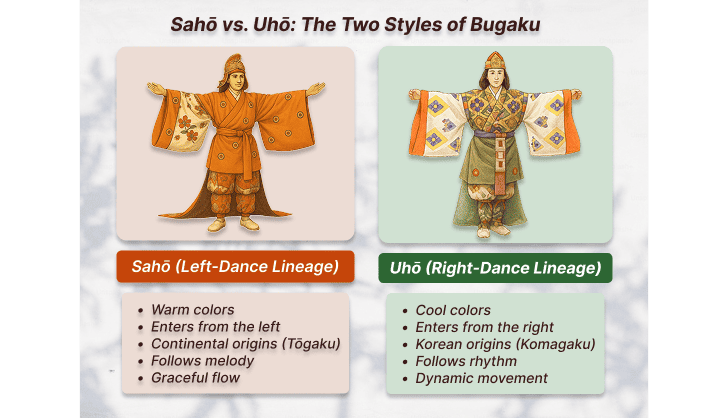

1. The Two Lineages of Bugaku: Sahō and Uhō

Bugaku is traditionally divided into two major lineages, each with its own origin, style, and visual character.

Sahō (左方 / Left-Dance Lineage)

Derived from Tōgaku, which traces its roots to the musical and dance traditions of Tang China and the broader Asian continent.

Key features include:

- Costumes in red and other warm colors

- Dancers enter from the left side at the back of the stage

- The dance is performed in sync with the melody, meaning the beginning and ending of the dance align with the musical phrasing

Uhō (右方 / Right-Dance Lineage)

Based on Komagaku, a tradition influenced by the performing arts of the Korean Peninsula.

Its characteristics include:

- Costumes in green, blue, and other cool colors

- Dancers enter from the right side at the back of the stage

- Movements follow the rhythm, so the timing of the dance does not necessarily align with the melodic structure

Both lineages are accompanied by wind and percussion instruments, yet their musical character differs due to their distinct origins.

These classifications were formalized during the Heian period, when imported dances and instruments were carefully reorganized.

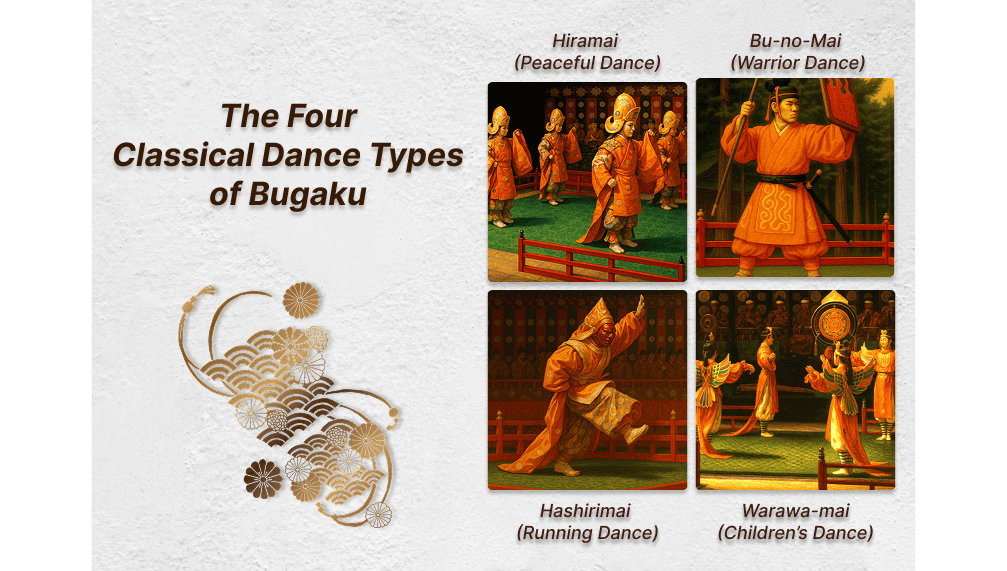

2. Four Classical Categories of Bugaku

Since ancient times, Bugaku has been divided into four principal dance types, each with its own distinct character and performance style.

-

Hiramai (平舞, “Peaceful Dance”)

A graceful, abstract dance performed at a calm, steady tempo.

Four or six dancers move in balanced, symmetrical patterns while changing directions. -

Bu-no-Mai (武舞, “Warrior Dance”)

A powerful dance performed with weapons such as swords, shields, or halberds.

Danced by one or four performers, it expresses the formations and movements of warriors on the battlefield. -

Hashirimai (走舞, “Running Dance”)

A lively, fast-paced dance performed by one or two dancers.

The music features quicker tempos and characteristic melodies, and many pieces draw inspiration from legends or heroic tales. -

Warawa-mai (童舞, “Children’s Dance”)

Performed by young dancers wearing child-sized versions of adult costumes.

Masks are not used; instead, dancers wear traditional white face makeup, creating a charming and bright stage presence.

These categories emphasize dignified, abstract beauty rather than literal storytelling—one of the defining aesthetics of Bugaku.

3. The Movement System: Mai-no-Te (舞の手)

Bugaku does not aim to express specific emotions or imitate real-life actions.

Instead, it conveys abstract elegance through a highly codified system of movements known as mai-no-te.

The primary categories of movement include:

- Head and Neck Techniques (用首法) — Techniques involving controlled movements of the head and neck

- Hand and Arm Techniques (用手法) — Stylized gestures of the hands and arms

- Leg and Footwork Techniques (用足法) — Regulated footwork and precise stepping patterns

- Bending and Stretching Techniques (屈伸法) — Ritualized bending and extending of the body

These are combined with additional choreographic elements such as:

- The dancer’s orientation and stage position

- Methods of walking, stepping, or turning

- The intentional use of stillness and ma (間)

Together, these components create movements that are formal, symbolic, and non-narrative, emphasizing dignity over dramatization.

In some traditions, the exact forms of mai-no-te differ between Sahō (left) and Uhō (right) dances, reflecting their distinct historical lineages.

The movement principles of Bugaku reveal that Gagaku’s mysterious, otherworldly atmosphere is shaped not only by its music, but also by the refined and ceremonial elegance of the dancers who bring this ancient art to life.

Costumes and Masks of Gagaku and Bugaku

Gagaku’s appeal lies not only in its music and dance.

The costumes, masks, and ceremonial accessories worn by musicians and dancers also play an essential role.

Let’s take a closer look at the world of garments and attire that bring Gagaku’s visual beauty to life.

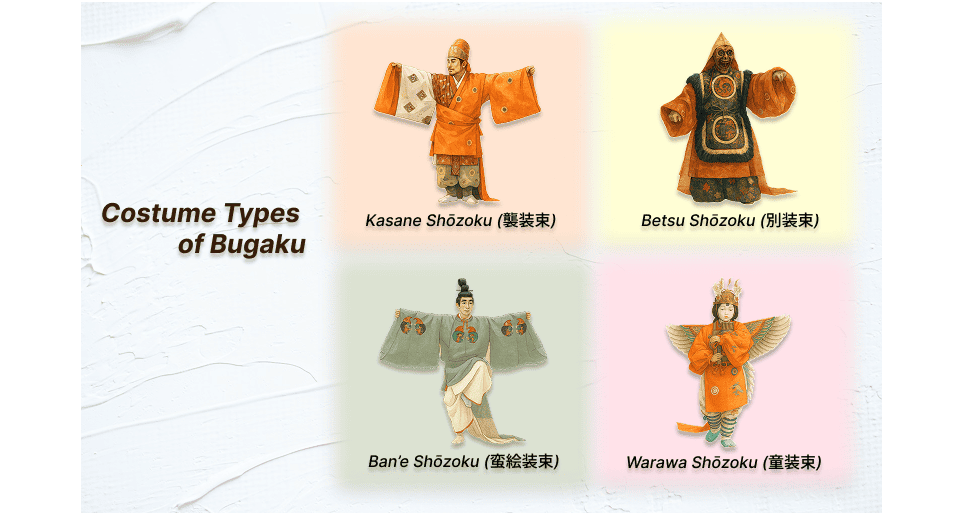

Costumes of Bugaku — Ceremonial Elegance in Motion

Bugaku costumes vary depending on the dance, its cultural origin, and the lineage through which it was transmitted.

Broadly, Bugaku costumes are divided into four categories:

- Kasane Shōzoku (襲装束) — The most commonly used Bugaku costume, consisting of multiple layered robes inspired by the elegant styles of Tang-dynasty China.

- Ban’e Shōzoku (蛮絵装束) — A light, elegant costume decorated with round warrior-style emblems. These circular motifs traditionally feature paired Tang-style lions embroidered onto the robe.

- Betsu Shōzoku (別装束) — Unique costumes prepared specifically for individual dances, ranging from lavishly ornate to simple and restrained, chosen to match the character of each piece.

- Warawa Shōzoku (童装束) — Child-sized versions of adult costumes, sometimes adorned with wing-like ornaments inspired by birds or butterflies.

Costume Color Traditions in Bugaku Lineages

Because Bugaku includes dances of different origins, each lineage has developed its own distinctive color palette and visual style.

| Tradition / Origin | Typical Colors | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Tōgaku (唐楽 / Continental Origin) | Bright reds, warm tones | Tang-influenced designs; vivid, ornate, and richly decorated |

| Komagaku (高麗楽 / Korean-Influenced) | Greens, blues, cool tones | Gentle, refined color palette reflecting Korean aesthetics |

| Kuniburi no Utamai (国風歌舞 / Indigenous) | Simple, white-based garments | Rustic, pure, and minimal, expressing ancient Japanese ritual style |

These visual differences allow audiences to identify the cultural lineage of each dance at a glance, deepening the historical context behind every performance.

Masks (仮面) — Expressive yet Symbolic

In some dances, performers wear distinctive masks to enhance the visual impact of the performance.

These masks come in a wide variety of forms, often representing human faces or animals.

They are typically carved from wood—most commonly paulownia, cypress, or camphor—and finished with great craftsmanship.

Their expressions range from stern and dignified to humorous or drunken, allowing each mask to convey the emotional character of the figure portrayed in the dance.

Accessories and Props (持物)

In addition to costumes and masks, Bugaku dancers also use distinctive headpieces and ceremonial props that enhance the visual and symbolic qualities of the performance.

Headpieces

There are two main types of headgear worn in Bugaku:

- Kabuto (甲) — A helmet-like headpiece.

- Kanmuri (冠) — A ceremonial crown used for specific roles and dances.

Handheld Props (舞具)

Bugaku also features a wide variety of props known collectively as maigu. These vary greatly in size, color, and design, and may include:

- Baton-like tools, such as shaku (笏)

- Drumsticks, such as bachi (桴)

- Weapons, such as ceremonial swords (太刀)

Some dances use special props to emphasize dramatic or symbolic elements of the story:

- A wooden serpent to portray the act of capturing a snake

- A ball-and-rod set (球杖) for dances depicting ball games or athletic scenes

These accessories enrich the performance, adding depth and vivid visual expression to Bugaku’s ceremonial world.

Together, these costumes, masks, and accessories form the visual identity of Gagaku and Bugaku.

They serve as essential elements that complete Gagaku as a total art form — adding color, silhouette, and visual presence to its world of sound and movement.

Where to Experience Gagaku Today

Have you felt inspired to experience the world of Gagaku for yourself?

There are several places in Japan where you can encounter this ancient tradition directly.

Here are some accessible locations where visitors can enjoy Gagaku as part of their travels.

Japan Gagaku Society Public Concerts

For many years, public Gagaku concerts organized by the Japan Gagaku Society (日本雅楽会) were held at the National Theatre of Japan in Tokyo.

These programs typically featured kangen (instrumental music), bugaku (dance), and short explanations, making them an ideal introduction for first-time audiences.

The National Theatre is currently closed for large-scale reconstruction, so the annual Gagaku concert has been temporarily relocated to the:

- Shinjuku Ward Yotsuya Civic Hall

The latest information on dates, tickets, and programs can be found on the official website of the Japan Gagaku Society:

The Latest Concert Information from the Japan Gagaku Society

(Information is available in Japanese only, and there is currently no official English translation.)

Imperial Household Agency – Public Gagaku Performances

The Imperial Household Agency’s Music Department (Gakubu) also presents several official Gagaku performances each year.

While many of these concerts are intended for cultural organizations or diplomatic guests, one annual performance is open to the general public.

- Autumn Gagaku Performance — Open to the Public Held each autumn inside the Imperial Palace, this is the only yearly performance that the general public may attend through an application process.

The official information page for the Autumn Gagaku Performance is available only in Japanese, but it provides full details about the concert and allows you to submit an application:

Detail information

This concert provides a rare chance to hear Gagaku performed by the Imperial Household Agency’s Music Department in an authentic imperial setting.

Shrines with Traditional Gagaku Offerings

Certain major shrines continue to offer Gagaku and bugaku as part of their sacred festivals. These performances allow audiences to experience Gagaku in the setting closest to its ancient origins.

Representative examples include:

- Ise Grand Shrine (Mie) — Gagaku and kagura are performed during major festivals such as the Kangetsusai (April) and Kannamesai (October)

- Kasuga Taisha (Nara) — Manyō Gagaku Performance held annually on November 3rd (Culture Day)

Most events are open to the public without reservation, but arriving early is recommended due to large crowds.

Universities and Cultural Ensembles

Groups such as the Kitanodai Gagaku Ensemble and university Gagaku clubs frequently hold concerts, workshops, and educational events.

These performances are often more informal and accessible, making them an excellent option for those encountering Gagaku for the first time.

You can find event schedules and information on their official website.

Although opportunities to hear Gagaku may be limited, each performance offers a precious encounter with a living tradition that has resonated across Japan for more than a thousand years.

If you ever have the chance to visit Japan, I hope you will take a moment to experience its sound and atmosphere for yourself.

Even a single performance can open a window into Japan’s oldest musical tradition — one that continues to resonate quietly in the modern world.

A small break — a little side note

Gagaku is traditionally known through its formal, classical performances —

but how about experiencing a modern arrangement as well?

Gagaku is an ancient Japanese art, yet it continues to breathe gently within today’s music.

When “Homura,” one of the theme songs from Demon Slayer, is performed with Gagaku instruments,

its emotions deepen — a blend of sorrow, warmth, and quiet strength.

Take a moment to listen, and enjoy this gentle fusion of tradition and the present.

Conclusion: A Living Tradition Shaped by Sound, Movement, and Spirit

Gagaku is far more than ancient court music.

It is a living cultural heritage woven from sound, dance, costume, ritual, and over a thousand years of history.

Through its journey from the Heian court to modern theatres and shrines, Gagaku has continued to evolve while preserving its profound sense of dignity and serenity.

Today, Gagaku remains alive — not as a relic, but as a tradition that continues to be performed, studied, taught, and cherished across Japan.

If you ever find yourself in Japan, I hope you will take a moment to experience it firsthand:

the stillness between the notes, the colors of the costumes, the measured steps of the dancers — and the timeless world that opens when music, ritual, and history come together.