The Heian Aristocrats: Beauty, Culture, and Their Enduring Legacy in Japan

Colors blooming through layers of silk.

Poems whispering hidden feelings.

Court games played purely for the beauty of their movement.

This was everyday life for the aristocrats of Japan’s Heian period — a golden age in which elegance shaped everything from fashion to literature.

What kind of days unfolded behind the palace screens? And how have their tastes and sensibilities continued to influence Japan for more than a thousand years?

Let us open the door to their radiant world and begin a journey together — a journey into a life filled with charm, creativity, and timeless style.

What Were the Japanese Aristocrats?

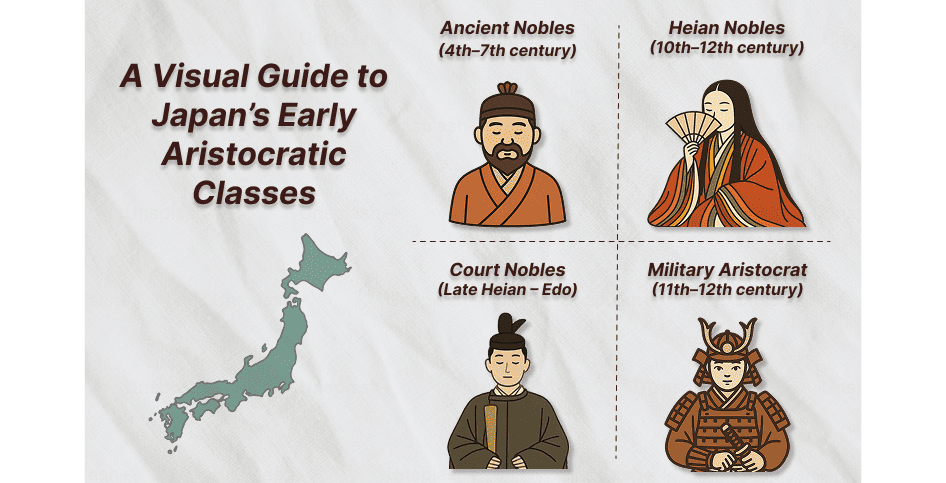

Before exploring the graceful world of the Heian aristocrats, let’s take a moment to look at Japanese nobles more broadly.

While the Heian courtiers are the most famous today, Japan’s aristocracy actually took many forms throughout history.

In Japan, the word “aristocrats” (kizoku, 貴族) referred to a privileged class distinct from ordinary people — though their roles and status varied greatly from era to era.

In this section, we’ll briefly explore the different kinds of nobles who appeared across Japanese history, and how each group fit into the changing shape of the nation.

Aristocrats from Ancient Times to the Heian Court

To begin, let’s look at the nobles who shaped Japan from its earliest eras up to the Heian period.

-

Ancient Nobles (Kodai Kizoku, 古代貴族)

Beginning around the 4th century with the rise of the Yamato state (大和王権), these were powerful clan leaders (gōzoku, 豪族) who supported early rulers known as ōkimi (大王).

They formed the foundation of Japan’s earliest political structure. -

Heian Nobles (Heian Kizoku, 平安貴族)

By the mid to late Heian period (10th–12th centuries), the nobles of the capital dominated politics, society, and culture.

This era saw the blossoming of kokufū bunka (国風文化) — a refined, uniquely Japanese court culture known for poetry, fragrance, and layered silk robes. -

Court Nobles – Kuge (公家)

From the late Heian period onward, these aristocrats served the imperial court as high-ranking officials.

Their world revolved around rituals, ceremonies, and civil administration (bunji, 文治), upholding the authority of the emperor. -

Military Aristocrats (Gunji Kizoku, 軍事貴族)

Emerging from the lower ranks of the aristocracy, these nobles specialized in military matters.

Over time, they formed the foundation of the samurai class that would later shape Japanese history.

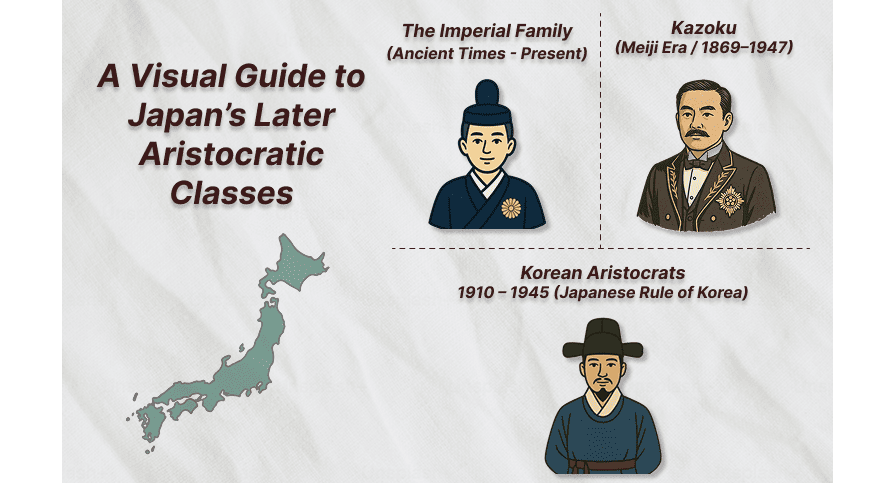

Aristocrats in Later Japanese History

Let’s continue our journey by looking at the aristocrats who lived in Japan’s later historical periods.

-

The Imperial Family (Kōzoku, 皇族)

Descendants of the emperor and members of Japan’s royal household.

The imperial family is often described as the world’s oldest continuous hereditary monarchy, and it remains today as a symbolic presence. -

Kazoku (華族)

A modern-style noble class created between 1869 and 1947.

Former court nobles (kuge) and feudal lords (daimyō) were reorganized into a Western-style peerage of five ranks — duke, marquis, count, viscount, and baron. -

Korean Aristocrats (Chōsen Kizoku, 朝鮮貴族)

Established in 1910 after Japan’s annexation of Korea.

This title, created under Japan’s rule of Korea, was granted to certain elites, including members of the former Yi royal family and other distinguished Koreans recognized for their lineage or service.

The End of Aristocracy in Japan

Throughout history, many different forms of aristocracy appeared in Japan.

However, after World War II, the 1947 Constitution officially brought all noble titles to an end.

The only exception was the imperial family, which continues today as a cultural and symbolic institution.

From ancient clan leaders to the elegant courtiers of the Heian period, and finally to the modern kazoku peerage, Japan’s aristocrats were never a single, uniform group.

Each era shaped its nobles in different ways, and each left behind cultural legacies that still influence Japan today.

How Japanese Aristocrats Differed from Western Nobles

When you hear the word “aristocrat,” you may picture European nobles — people who lived in stone castles, led armies, and hosted grand feasts.

But the lives of the Heian aristocrats were entirely different from this image.

Let’s take a closer look at how their lifestyle — and the way they expressed status — differed from that of Western nobles.

How the Heian Nobles Expressed Status

One of the defining features of the Heian aristocrats was that they did not show their status through warfare.

Instead, they expressed prestige through rituals, poetry, and a refined sense of beauty.

Influenced by the concept of ritual purity (kegare), they generally avoided military matters and showed little interest in fighting or policing.

Their world revolved around elegance, delicacy, and artistic skill.

Key Differences from Western Nobles

Here are some of the major ways in which their lifestyle and values differed from those of Western nobles:

- Emphasis on culture over combat

– While European lords often earned prestige on the battlefield, Japanese nobles gained honor through waka poetry, the creation of the kana syllabary, and a deep appreciation for seasonal beauty.

Their legacy lives on in the many literary works they left behind. - A life centered on the imperial court

– Instead of castles and fortifications, their world centered on the imperial court in Kyoto.

Homes built in the shinden-zukuri style opened onto gardens, and daily life was filled with ceremonies, festivals, and graceful pastimes like kemari (kickball) and gagaku court music. - Aesthetic values as a measure of refinement

– Status was expressed through layered robes such as the jūnihitoe, delicate fragrances, and an exquisite sensitivity to seasonal change — not through armor, weapons, or land.

In short, while Western nobles showed their power through strength and warfare, the Heian nobles embodied prestige through elegance, culture, and refined artistic sensibility.

Daily Life in the Heian Court

What was daily life like for the nobles who valued elegance far more than warfare in the Heian court?

The Heian period lasted for nearly 400 years, but it was in the mid to late Heian era that aristocratic culture truly blossomed into something uniquely Japanese.

Let’s take a slow, gentle look into their world and explore everything from their fashion to their favorite pastimes.

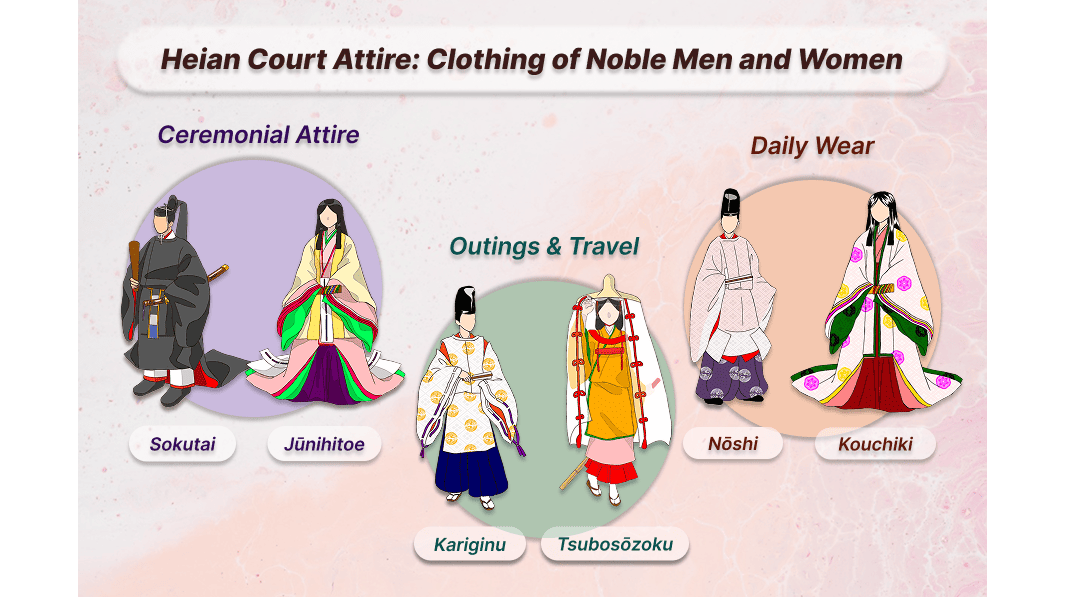

Clothing and Fashion

For the Heian nobles, clothing was more than something to wear—it was a way to show rank, taste, and refinement.

Men of the highest ranks wore the sokutai (束帯) during official rituals.

Women, meanwhile, appeared in the breathtaking jūnihitoe (十二単), a set of layered silk robes that could weigh up to 10 kilograms.

Outside formal events, men used lighter robes such as kariginu for outings, while women wore traveling outfits like tsubosōzoku.

At home, both dressed more simply in garments such as nōshi or kouchiki.

What truly mattered was elegance: the harmony of colors, the choice of seasonal motifs, and the subtle layering that expressed sensitivity to nature.

A well-chosen color combination could speak volumes about one’s taste and refinement.

A small break — a little side note

Did you know that in Japan you can still experience wearing the jūnihitoe (十二単), the most elegant court dress of the Heian period?

This video takes you behind the scenes of the dressing process—from makeup to layering—so you can see how someone is transformed into a Heian noble in no time.

You’ll also discover a fun secret: the outfit doesn’t actually use twelve separate robes, but layers arranged to look like twelve.

Ever wondered what the parts of the jūnihitoe are, or how it all fits together?

This video unravels the mystery—take a look and step into the dazzling world of Japan’s aristocrats!

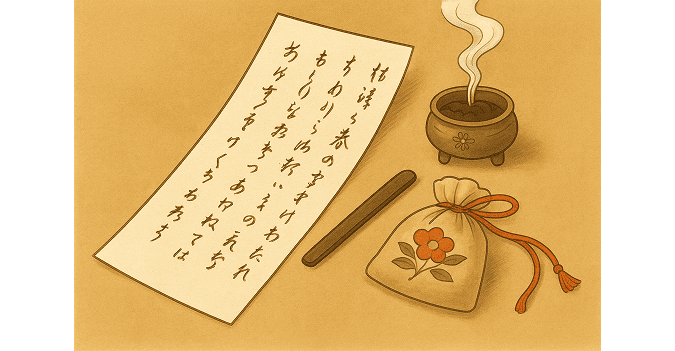

Poetry and Romance

For the Heian aristocracy, waka poetry was the language of emotion.

It shaped conversation, conveyed affection, and even played a central role in courtship.

Rather than speaking directly, a nobleman would send a poem—often written on beautifully scented paper or attached to a flower.

A woman’s handwritten reply was more than an answer; it signaled whether a romance might begin.

In this world, elegance of expression, sensitivity to nature, and literary skill mattered far more than appearance.

Poetry contests, or uta-awase (歌合), brought nobles together to test their wit and imagination in friendly yet refined rivalry.

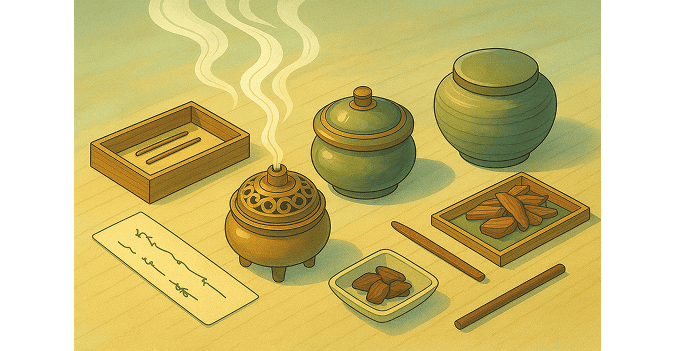

Fragrance and the Joy of the Senses

The Heian court was a world filled not only with color and poetry but also with fragrance.

Nobles blended incense from herbs and aromatic woods to create scents that reflected their personal taste.

Their garments were perfumed so that a gentle aroma would linger on the layers of silk as they moved.

Fans, letters, and even poetry paper carried fragrance — transforming words into experiences for all the senses.

A refined sense of smell was admired as much as a talent for poetry or fashion.

In the Heian world, fragrance was not merely a luxury; it was a way of expressing character, taste, and subtle elegance.

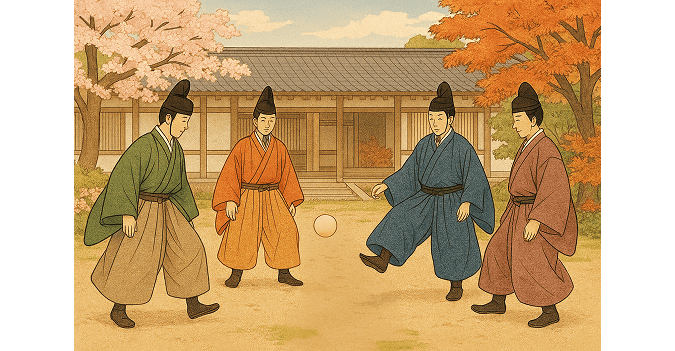

Games and Entertainment

Life in the Heian court included plenty of graceful pastimes and leisurely games.

- Dakyū (打毬) – a dynamic horseback sport similar to polo.

- Kemari (蹴鞠) – a cooperative game where players kept a leather ball aloft, focusing on beauty rather than competition.

- Kai-awase (貝合わせ) – a matching game using painted clamshells, loved for its artistry.

- Go (囲碁) and Sugoroku (双六) – popular board games that mixed strategy with relaxation.

Music and dance were equally essential.

Nobles played the koto (琴), flute (笛), and biwa (琵琶), filling palace gardens with elegant sounds during festivals and seasonal celebrations.

A small break — a little side note

How did the nobles of the Heian court spend their free time?

This video brings their world vividly to life through kemari—a graceful ball game where players, dressed in aristocratic robes, form a circle and keep the ball aloft.

It’s not about kicking the ball across a field like soccer, but about keeping it in the air, passing it elegantly from one noble to another.

It may look difficult, yet in this reenactment you’ll see how beautifully they manage to keep the rally going!

Thanks to the Kemari Preservation Society, this ancient pastime is not only performed for audiences but also offered as an interactive experience, allowing visitors to try for themselves the very game once loved by Japan’s aristocrats.

Daily life for the Heian aristocrats was not shaped by war or political ambition, but by the pursuit of beauty — through clothing, poetry, fragrance, games, and music.

In their world, everyday life itself became an art—filled with small moments of beauty, creativity, and graceful expression.

Arts and Literature of the Nobility

The graceful lifestyle of the Heian nobles was deeply reflected in the art and literature of their time.

Many of the cultural forms that emerged during this era became the very foundation of Japanese tradition, and their influence can still be felt today.

Let’s take a closer look at the artistic world they created.

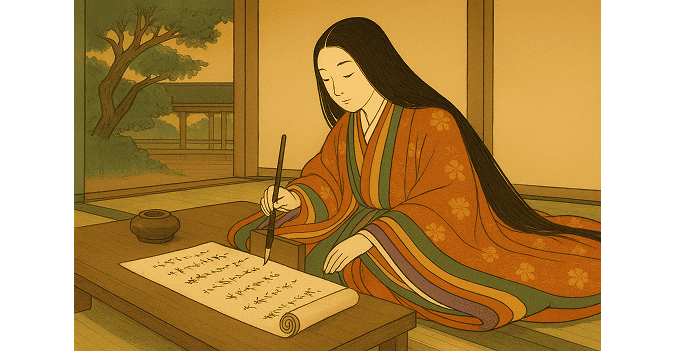

The Rise of Kana and Women’s Literature

One of the most important cultural achievements of the era was the development of the kana syllabary (仮名).

Compared to Chinese characters, kana allowed people—especially women of the court—to write with greater freedom and emotional nuance.

Thanks to this new script, court women produced literary masterpieces such as Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji and Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book, works that continue to be celebrated around the world today.

Calligraphy and the Way of Writing

The blending of kanji and kana gave birth to a distinctly Japanese style of calligraphy known as wayō shodō (和様書道).

Soft, flowing, and elegant, this style reflected the refined tastes of the court.

Beautiful handwriting was more than decoration—it was considered a window into one’s character.

The balance of each stroke and the grace of each line could shape how a person’s refinement was judged in society.

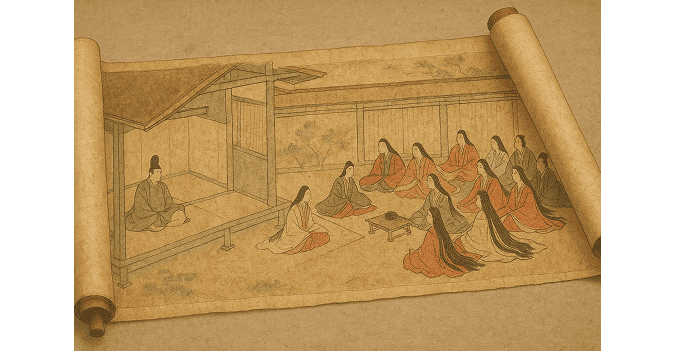

Painting and Picture Scrolls

Visual storytelling also bloomed in the form of emaki (絵巻物, picture scrolls).

Rather than aiming for realistic perspective, artists painted continuous scenes that unfolded like a story across the scroll.

This focus on narrative over realism is often seen as a distant ancestor of modern Japanese manga and other forms of illustrated storytelling.

Through literature, calligraphy, and painting, the Heian nobles built artistic traditions that went far beyond simple courtly elegance.

In fact, some of the Japanese arts and cultural styles you may imagine today are deeply connected to the creativity they cultivated.

Their refined sensibilities helped shape the very foundations of Japanese culture, and those traditions continue to inspire and captivate people even now.

Legacy of the Aristocrats in Modern Japan

As we’ve seen, the elegant world created by the Heian nobles has been carried forward into many of Japan’s traditions and cultural practices.

But did you know that traces of their world are also woven into the everyday life of modern Japanese people?

Let’s take a closer look at how their influence continues to appear in today’s society.

Kimono and Courtly Dress

The Heian nobles’ love for layered robes and seasonal colors can still be felt in Japanese fashion today.

Even in daily clothing, many people enjoy expressing style through layering—letting a hint of color peek from beneath a jacket, or choosing different lengths to create depth and movement.

Colors and patterns also reflect the seasons: soft pastels in spring, rich earth tones in autumn, and fabrics chosen to match the atmosphere of the moment.

This attention to color harmony and layering feels like a modern reflection of the Heian nobles’ elegant approach to dress.

The same sensibility lives on in formal kimono etiquette, where every fabric, shade, and accessory is chosen with care and meaning.

Sensitivity to the Seasons

The Heian nobles held a deep appreciation for the changing seasons through poetry, color, and fragrance — a sensitivity that remains a natural part of Japanese life today.

In spring, people gather under blooming cherry blossoms for hanami, enjoying both the beauty of the moment and the gentle sadness of its passing.

In autumn, they admire the vibrant red leaves, feeling awe and a quiet farewell to the season before winter arrives.

This connection to nature also appears in Japanese literature: the waka beloved by Heian nobles has evolved into tanka and haiku.

Their love of fragrance lives on as kōdō (the Way of Incense) — a traditional art that delights the senses alongside the tea ceremony.

Although the forms have changed, the same elements — music, color, poetry, and scent — remain woven into Japanese life today.

Etiquette and Aesthetics

The Heian nobles valued refinement, subtlety, and elegance, and these ideas still shape modern Japanese manners.

From childhood, people learn to show courtesy — through table etiquette, respectful language (keigo), and the custom of bowing in daily interactions.

These values also appear in traditional arts: the poised movements of the tea ceremony, the respectful bows of martial arts, and the graceful posture of ikebana all carry the spirit of Heian elegance into the present.

In this way, many of the aesthetic values cherished in Japan today can be traced back to the world of the Heian nobles.

The sensibilities and refined sense of beauty they cultivated have become part of everyday Japanese awareness and character, remaining alive in gentle but enduring ways.

Conclusion: The Lasting Legacy of Japan’s Aristocrats

Japan’s aristocrats may now be part of history, yet the Heian nobles remain the most vivid and influential image of what aristocratic society meant in Japan.

Unlike many noble classes around the world, their power was expressed not through force, but through poetry, seasonal awareness, ritual beauty, and a uniquely refined way of life.

The values they cultivated continue to shape the sensibilities of modern Japan in profound ways — from literature and calligraphy to the nation’s deep appreciation for the seasons, everyday etiquette, and even the aesthetics of contemporary fashion.

These influences are not distant relics; they are quiet forces that still guide Japanese taste, behavior, and cultural identity.

Exploring the world of Japan’s aristocrats is not just a journey into the past.

It is a way to understand the subtle cultural heartbeat of Japan, a rhythm that began more than a thousand years ago and continues to resonate today.

As you encounter Japan—its manners, its arts, its sensitivity to nature — you may find traces of the elegance the Heian nobles once cherished, still alive, still luminous, and still shaping the spirit of Japan.