Fūjin and Raijin: The Eternal Dance of Wind and Thunder

Imagine storm clouds swirling above. Thunder booms, and the wind howls across the sky.

Out of this chaos appear two fierce figures: Fūjin, the God of Wind, with his great bag of gales, and Raijin, the God of Thunder, striking his ring of drums.

With hair flying and bodies wrapped in clouds, they are not mere gods — they are the storm itself.

Feared for their might yet revered for their blessings, the people of Japan have long worshiped these tempestuous deities with awe and respect.

But long ago, the two storm gods followed very different paths.

Why, then, are they now imagined as an inseparable pair?

How did wind and thunder become Japan’s most legendary duo?

Let’s begin the journey to uncover the story of Fūjin and Raijin — the eternal dance of wind and thunder.

Modern Perception – Fūjin and Raijin as a Pair

Before diving into their ancient origins, let’s look at how Fūjin and Raijin are seen in Japan today — what kind of images they inspire, what roles they play, and why these two storm gods have become such an unshakable pair in the nation’s imagination.

An Iconic Duo in Japanese Culture

In Japan today, Fūjin (the God of Wind) and Raijin (the God of Thunder) are almost never seen apart.

They are the ultimate storm duo — symbols of nature’s wild, untamed power.

Much of this lasting image comes from one unforgettable masterpiece: Tawaraya Sōtatsu (俵屋宗達, an early Edo-period painter), and his work “Fūjin Raijin-zu Byōbu” (Wind and Thunder Gods Folding Screens), painted in the early 1600s.

You may have seen it yourself — in a museum, a photo book, or even online — its golden panels glowing with divine energy.

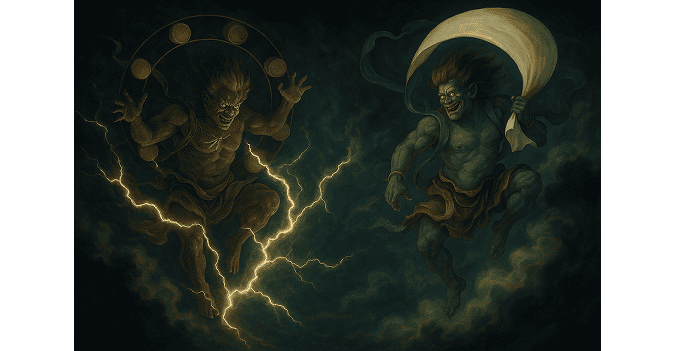

On the shimmering gold background, the two deities face each other.

Fūjin races through the air with his great wind bag, while Raijin stands within a halo of drums, ready to strike.

Together, they capture the essence of a storm — balance, motion, and divine power.

This iconic byōbu (屏風, folding screen) left such a strong impression that even today, most people imagine Fūjin and Raijin as eternal companions.

Through Sōtatsu’s vision, the two storm gods became forever linked — not just in art, but in the collective imagination of Japan.

From Fine Art to Famous Landmarks

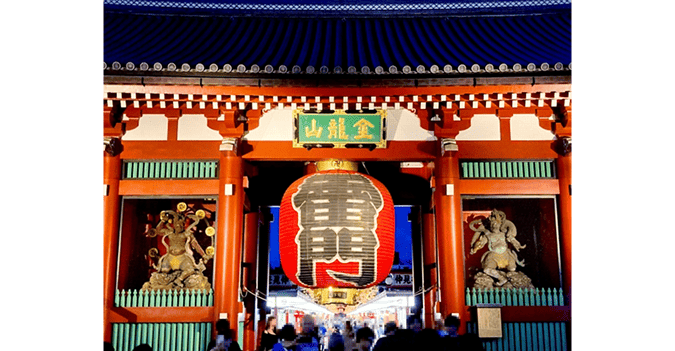

Do you think you need to visit a museum to see Fūjin and Raijin?

Actually, you don’t — there’s a famous place right in Tokyo where you can meet them face to face: the legendary Kaminarimon (雷門, “Thunder Gate”) at Sensō-ji Temple (浅草寺, Tokyo’s oldest temple) in Asakusa.

Here, the two storm gods — Fūjin and Raijin — stand on either side of the gate as powerful guardians, watching over everyone who passes beneath with their commanding presence.

Their fierce yet protective gazes welcome millions of visitors each year, making the gate one of Japan’s most recognizable and beloved landmarks.

Standing before it, you can instantly feel the harmony between them — the wind that drives the storm and the thunder that gives it a voice.

A small break — a little side note

Have you ever wanted to see Japan’s famous Fūjin and Raijin statues at Tokyo’s Kaminarimon Gate (Thunder Gate)—but can’t travel all the way to Japan?

This short video takes you right there!

You’ll meet Fūjin (on the right) and Raijin (on the left) standing proudly at the gate’s entrance.

And here’s a fun secret: behind the gate, you’ll find another pair of guardian deities — the Dragon Gods, one male and one female, completing the balance of wind, thunder, and water.

No matter the form, you’ll find that Fūjin and Raijin always appear side by side in Japan today.

Whether shimmering on a golden screen or standing guard at a temple gate, they remain bound together — an inseparable pair born of wind and thunder, forever echoing through Japan’s imagination.

When Wind Met Thunder – The Origins of Japan’s Storm Gods

We’ve seen how Fūjin and Raijin are viewed in Japan today. Now, let’s take a step back and explore how they came to form the iconic storm duo we know — tracing the moments that first brought wind and thunder together as one.

Why Wind and Thunder Belong Together

In Japan, Fūjin and Raijin were not always seen as a pair.

Originally, they were independent deities, each worshiped for different reasons.

The idea of them forming a divine duo developed gradually over the long course of Japanese history.

It’s true that Tawaraya Sōtatsu’s masterpiece later solidified their image as inseparable companions, but the concept of wind and thunder moving together had already taken root long before his time.

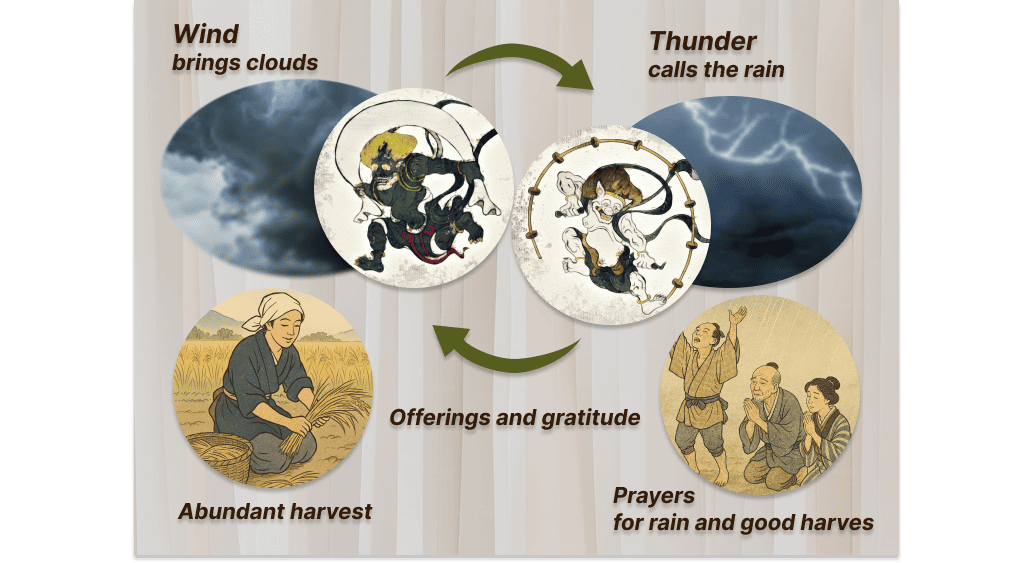

Imagine a storm: the wind stirs the air, and thunder shakes the heavens. These two forces move as one — bringing both destruction and renewal.

It’s no wonder that, since ancient times, wind and thunder have been seen as inseparable partners.

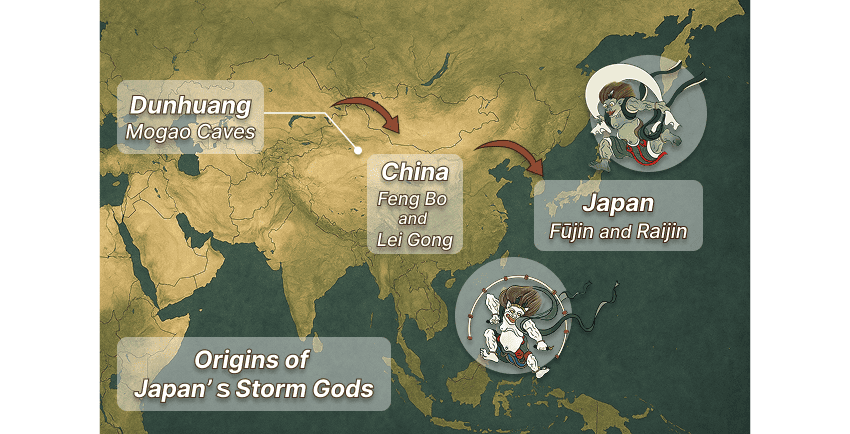

This idea is not unique to Japan, but deeply rooted in ancient Asian traditions.

Across Asia, wind and thunder often appeared side by side in mythology and art:

- China — In Chinese mythology, Feng Bo (the Earl of Wind) and Lei Gong (the Duke of Thunder) are depicted in harmony, working together as complementary forces of nature.

- Central Asia — In the Buddhist murals of the Mogao Caves in Dunhuang, wind and thunder deities guard sacred halls, their powers perfectly balanced.

As Buddhism spread to Japan, these ideas merged with native Shinto beliefs and local storm legends.

Over time, these ideas came together and people began to picture Fūjin and Raijin as a pair — a partnership shaped by cultural exchange and Japan’s love for the harmony of nature.

Fūjin – God of the Wind

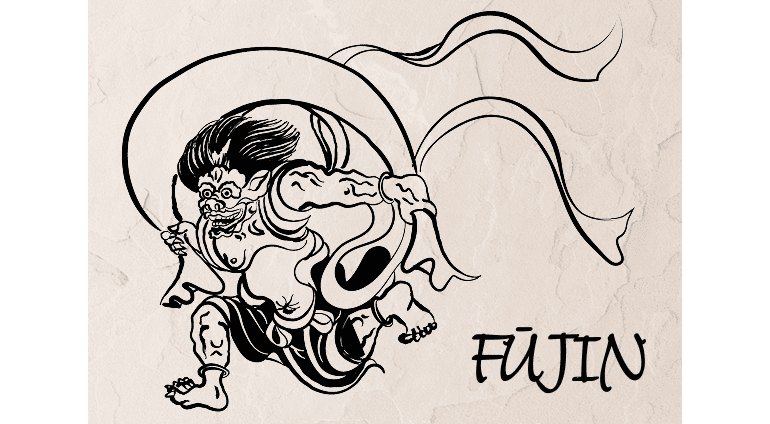

We’ve explored the connection between Fūjin and Raijin, but have you ever wondered — who is Fūjin himself?

In this section, we’ll take a closer look at the God of Wind — his origins, nature, and how his image has transformed through the ages.

Ancient Origins in Myth

According to Japan’s ancient chronicles, Fūjin’s origins differ depending on the text:

- In the Kojiki (古事記,Records of Ancient Matters, compiled in 712 CE), he appears as Shinatsuhiko, born from the divine couple Izanagi and Izanami.

- In the Nihon Shoki (日本書記, Chronicles of Japan, completed in 720 CE), he is known as Shinatobe-no-Mikoto, created from Izanami’s breath as she blew away the morning mist.

These early myths present Fūjin as a primordial force of nature — a spirit of movement and air that bridges the human world and the divine.

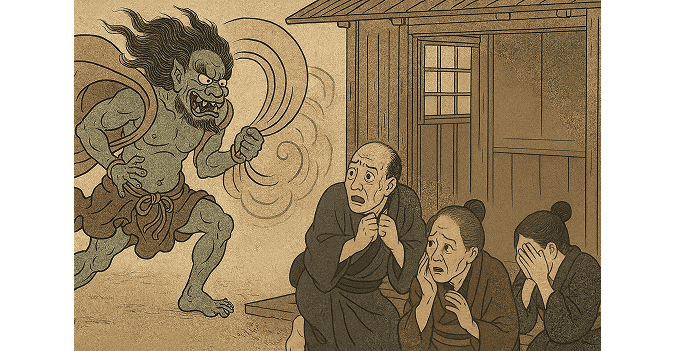

Feared and Revered in the Heian and Kamakura Periods

By the Heian (794–1185) and Kamakura (1185–1333) periods, strong seasonal winds and storms caused both fear and respect.

Because these tempests could destroy crops, ruin fishing grounds, and spread disease, people began to see Fūjin as an epidemic god (yakubyōgami).

Villagers held festivals and rituals to calm his fury, hoping fierce winds would turn into gentle, life-giving breezes.

Folklore and Rituals of the Edo Period

In Edo-period folklore (1603–1868), Fūjin took on a more personal and spiritual form.

He was described as a spirit riding the wind, slipping unseen into homes and breathing illness onto people.

During outbreaks, villagers crafted straw effigies of Fūjin and paraded them through the streets, chanting “Okure, okure!” (“Send it away!”) before casting them into rivers — a purification rite meant to drive away plague and misfortune.

Throughout history, Fūjin has been seen as the spirit of the wind — unseen yet ever-present.

People once feared his tempests. Through rituals and prayers, that fear slowly turned into reverence.

Over time, he came to symbolize harmony between humans and nature.

Even the wildest forces, when met with respect, can bring life.

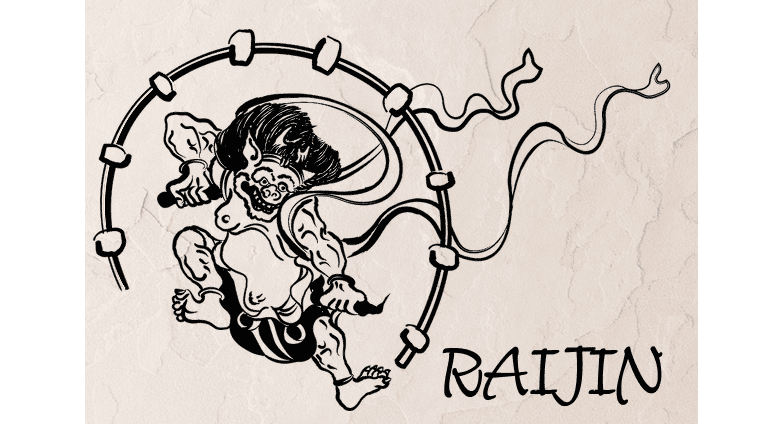

Raijin – God of Thunder

Now, let’s turn our attention to Raijin — the God of Thunder — and explore his origins, legends, and how his image evolved through the ages.

Origins in Myth and the Underworld

Raijin’s origins trace back to the underworld.

According to the Kojiki (Records of Ancient Matters), Raijin first appears after the death of the goddess Izanami.

In the underworld of Yomi, eight thunder deities emerged from her lifeless body — each born from a different part, representing thunder in the heart, head, and limbs, their rumbling forms symbolizing the divine power of storm and death.

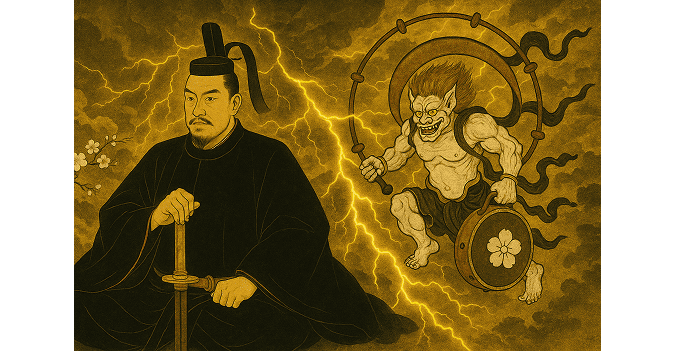

The Legacy of Sugawara no Michizane

Centuries later, Raijin’s story took a new turn through the legacy of the scholar Sugawara no Michizane (845–903).

After his death, a series of lightning strikes and natural disasters struck the capital, and people began to believe these were signs of Michizane’s anger.

To appease his spirit, Sugawara no Michizane (845–903) was later enshrined as Tenjin (天神) — a deity of both thunder and learning.

From this time onward, Raijin became closely associated with Tenjin — worshiped not only as a thunder god, but also as a protector of knowledge.

In folk belief, he is affectionately called Kaminari-sama, a familiar nickname that softens fear into respect and turns divine power into something close to the human heart.

Through his fusion with Tenjin, Raijin came to embody not only thunder’s power but also wisdom and learning.

He evolved from a feared storm god into a benevolent protector — linking nature’s energy with human hopes.

In this way, his image evolved beyond a force of destruction — transforming into a divine protector who connects nature’s fierce energy with human aspiration.

From Two Myths to One Storm

As we’ve already seen, Fūjin and Raijin were not always imagined as a pair.

Each was revered independently, for different purposes and beliefs.

Let’s take a look at a few examples of how they were honored individually.

- Some Shinto shrines, especially in rural regions, enshrined Fūjin alone — praying for protection from destructive winds and for rich harvests.

- Others worshiped Raijin for rainmaking, lightning protection, or as a patron of learning through the Tenjin faith.

- In Buddhist temples, statues of wind and thunder gods were sometimes placed separately in different halls or gates, reflecting their distinct spiritual roles.

Over the centuries, however, their paths began to converge — influenced by East Asian artistic traditions that paired wind and thunder, and by Japan’s own perception of storms as a single, living force.

Through centuries of belief and imagination, Fūjin and Raijin came to symbolize more than mere storm gods.

They became the living spirit of balance itself — where nature’s fury meets its beauty, and where the roar of thunder dances with the whisper of the wind across Japan’s skies.

The Artistic Legacy of Fūjin and Raijin

Today, Fūjin and Raijin are known as an inseparable pair.

But did you know that countless Japanese artists have been inspired by these storm gods throughout history?

Beyond Tawaraya Sōtatsu’s famous masterpiece, many painters across the centuries poured their own passion and creativity into depicting Fūjin and Raijin.

Let’s explore how Japanese art has kept their spirit alive through time.

Edo Period Interpretations (1603–1868)

During the Edo period, the theme of paired storm gods flourished across painting schools and popular culture.

Artists from the Kanō and Rinpa painting schools, as well as the Ukiyo-e tradition, gave the motif new life — faith and creativity came together.

- Kano Tanyū (1602–1674) — Created his own Fūjin Raijin-zu Byōbu, showcasing the bold, formal elegance of the Kanō school.

- Ogata Kōrin (1658–1716) — Reimagined the gods with softer forms and luminous color, now housed in the Tokyo National Museum.

- Sakai Hōitsu (1761–1828) — Painted his version on the reverse of Kōrin’s screens, creating a rare “dialogue” between two generations.

- Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) — Included the storm gods in his Hokusai Manga, portraying them with humor and dynamic movement.

- Kawahara Keiga (1786–?) — Produced designs influenced by Hokusai, reflecting the reach of popular print culture.

- Suzuki Kiitsu (1795–1858) — A disciple of Hōitsu, painted the Fūjin Raijin-zu Fusuma (sliding door panels), bringing the gods into architectural space.

A small break — a little side note

Ever wondered how Tawaraya Sōtatsu and later artists captured Japan’s storm gods?

This video explores how Fūjin and Raijin were portrayed across generations — from Sōtatsu’s brilliant gold-leaf folding screens to the imaginative interpretations of later painters.

Discover how each artist saw wind and thunder in their own way, blending tradition and creativity into timeless masterpieces.

Modern and Meiji-Era Revivals (1868–1945)

As Japan entered the Meiji period (1868–1912), a renewed fascination with the Rinpa school and Sōtatsu’s shimmering gold screens inspired modern painters to reinterpret Fūjin and Raijin for a new age — blending tradition with innovation.

- Tomita Keisen (1879–1936) — Created a four-fold screen (Takashimaya Historical Museum) with soft, flowing brushwork.

- Imamura Shikō (1880–1916) — Painted a striking two-panel set (Tokyo National Museum) with bold modern sensibility.

- Yasuda Yukihiko (1884–1978) — Produced a two-fold screen (Tōyama Memorial Museum) merging classical composition with quiet realism.

- Maeda Seison (1885–1977) — Painted a large single-panel work (Ehime’s Seki Art Museum) glowing with rich color and spiritual energy.

These works show that the image of Fūjin and Raijin was never bound to a single style or era.

Each generation of artists, inspired by those who came before, breathed new life into the storm gods with their own interpretations.

Their swirling forms continue to capture the drama of wind and thunder, and the eternal harmony between nature and art.

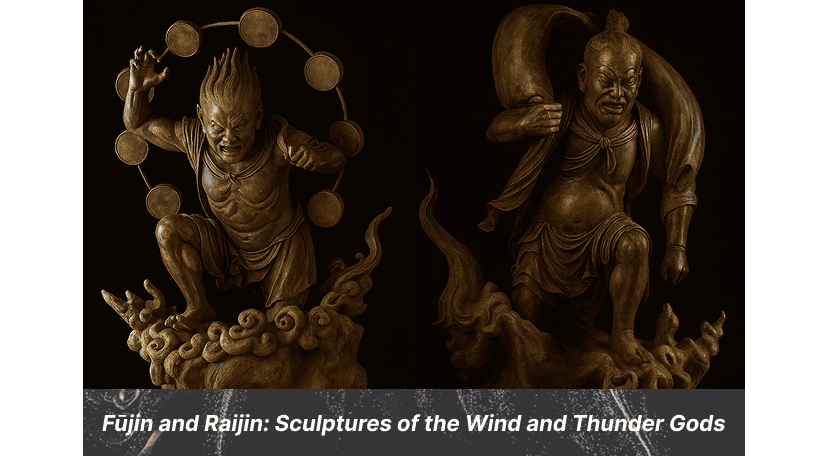

Sculptural Depictions of Fūjin and Raijin

While Fūjin and Raijin are celebrated in paintings and folding screens, their presence in sculpture is equally significant.

Across Japan, temples and gates have long enshrined the two storm gods as three-dimensional guardians, standing at the boundary between the sacred and the worldly.

In this section, we’ll explore how Fūjin and Raijin have been brought to life in sculpture — from sacred temple guardians to enduring symbols of divine power.

Medieval Origins – Kamakura Period (1185–1333)

The earliest surviving statues of Fūjin and Raijin date back to the Kamakura period, a time when religious sculpture flourished under the influence of both Buddhist devotion and realistic artistry.

Among these works, one of the most renowned examples can be found at Sanjūsangen-dō (Rengeō-in, Kyoto) — a temple famed for its thousand Kannon statues and its extraordinary guardian deities.

-

Sanjūsangen-dō (Rengeō-in, Kyoto)

The paired statues of Fūjin and Raijin at Sanjūsangen-dō (三十三間堂, Kyoto’s Rengeō-in Temple) were crafted by the Kei school (慶派, a group of Kamakura-period Buddhist sculptors).- Material: Wood, crafted using the yosegi-zukuri technique (寄木造, joined-block wood method) technique with traces of polychrome

- Design: Fūjin carries his great wind bag, Raijin wields a ring of drums — both captured in swirling motion that vividly expresses the invisible forces of the storm.

Originally, these figures served as guardians in Buddhist temples, embodying the power of natural forces under divine order.

These statues are even said to have inspired Tawaraya Sōtatsu’s renowned Fūjin Raijin-zu Byōbu, suggested by many scholars as a likely sculptural model for his painted gods.

Early Modern Era – Edo Period (1603–1868)

By the Edo period, the image of Fūjin and Raijin had spread far beyond temple halls and into the everyday faith of the people.

No longer confined to sacred sculptures, the storm gods began appearing at major city gates and shrines — standing as protectors of communities and symbols of prosperity.

-

Sensō-ji Temple, Kaminarimon Gate (Tokyo)

As mentioned earlier, the Kaminarimon Gate — today one of Tokyo’s most famous landmarks — has captivated visitors for centuries.

Since the Edo period, the gate has been flanked by large statues of Fūjin (north side) and Raijin (south side), serving both as spiritual guardians protecting the temple from floods and fires, and as iconic symbols welcoming travelers to the capital.- Roots: The gate, originally known as the Fūraijin-mon (“Gate of Wind and Thunder”), was moved to its current location in 1635, with statues of the gods placed in side chambers.

- History: It was destroyed by fire multiple times — most recently in 1865 — and stood in ruins for 95 years before its postwar reconstruction in 1960, when the current statues were commissioned by Matsushita Kōnosuke, founder of Panasonic, one of Japan’s most renowned electronics companies.

Characteristics of Sculptural Depictions

Across centuries of artistic expression, the sculptural forms of Fūjin and Raijin have shared several enduring traits.

Whether carved in wood, bronze, or stone, these divine figures are instantly recognizable through their poses, symbols, and placement.

Here are some of the defining characteristics that unite their depictions throughout Japanese history:

- Paired Guardianship — Fūjin and Raijin are almost always placed as a pair, positioned on opposite sides of temple gates or halls to ensure balance.

- Distinct Iconography —

- Fūjin: carries a large wind bag, his robes and hair billowing in invisible gusts.

- Raijin: surrounded by a halo of drums, his expression fierce, his stance commanding.

- Religious Function — Initially Buddhist protectors, they later appeared in Shinto shrines as nature’s divine guardians.

- Continuity of Form — Despite evolving aesthetics, their essential imagery has remained remarkably consistent from the Kamakura to the modern era.

Through sculpture, Fūjin and Raijin gained a tangible presence — not only as mythic figures, but as protectors standing watch over sacred spaces.

Carved in wood and reborn through centuries, these storm gods stand as timeless reminders of nature’s dual power — to destroy, and to protect — ever watching over those who walk beneath their gaze.

Cultural Significance Today

The image of Fūjin and Raijin has still alive and evolving even today.

These storm gods still appear across Japan — in festivals, products, and popular culture — embodying the nation’s unique ability to blend tradition and creativity.

Let’s take a closer look at how Fūjin and Raijin live on in modern Japanese culture.

Festivals and Folk Traditions

Across Japan, Fūjin and Raijin remain lively presences in festivals and local celebrations, where they are honored not only as divine protectors but also as emblems of energy and vitality.

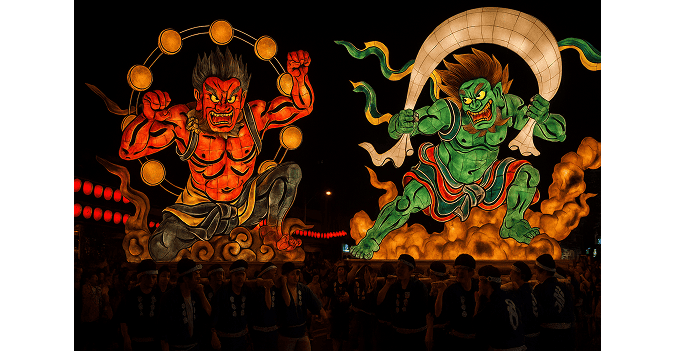

- Aomori Nebuta Matsuri (1993) — Featured a massive illuminated nebuta float depicting the two gods in fierce motion, fusing traditional craftsmanship with the spectacle of summer festival culture.

- Shinjō Matsuri (Yamagata, 2014) — Presented a festival float themed on Fūjin and Raijin, paraded through the streets as part of this UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage event.

Their imagery also appears in festival attire and goods — koi-kuchi shirts, drawstring bags, tenugui towels, obi belts, fans, and happi coats — letting participants “wear the storm” as part of the celebration.

Modern Pop Culture

Even in today’s entertainment world, the storm gods continue to inspire new forms of expression.

Their imagery, once bound to temples and scrolls, now charges across screens, comics, and games.

- NARUTO Shippuden 20th Anniversary Figures (2017) — Featured Naruto and Sasuke dressed as Fūjin and Raijin, with wind and lightning swirling around them — a striking homage to Japan’s mythic heroes.

- Countless other games, anime, and manga reinterpret the pair — sometimes as guardians, sometimes as rivals — keeping the spirit of wind and thunder alive in modern storytelling.

Contemporary Art

In the world of fine art, modern creators continue to reinvent the storm gods with fresh imagination.

- Takashi Murakami’s “Fūjin Raijin” (2024) — Exhibited at the Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art, this work reimagines the deities through silver-leaf pop art, transforming their once-fierce visages into charming, yuru-charalike expressions.

Murakami’s playful approach bridges ancient reverence and contemporary whimsy — proof that these timeless gods still evolve with Japan’s changing visual culture.

In this way, Fūjin and Raijin continue to inspire new interpretations — not only within the realms of faith and art, but also as familiar figures woven into everyday life.

They remain ever-present symbols of how Japan transforms ancient belief into a living, breathing culture.

Conclusion – The Enduring Storm

From ancient mythology to gilded folding screens, from temple gates to festival streets, Fūjin and Raijin have journeyed across centuries of Japanese history.

Once worshiped separately as the masters of wind and thunder, they became an inseparable pair — united through art, faith, and imagination.

Their images have guarded temples from floods and fires, inspired artists from Tawaraya Sōtatsu to Takashi Murakami, and danced through summer nights atop festival floats.

Even today, they appear on happi coats, fans, and festival banners — and even in comics, games, and charming mascots — proof that the storm gods still live in Japan’s imagination.

In their swirling clouds, we can feel both nature’s raw power and human creativity — always moving, changing, and inspiring, just like wind and thunder themselves.

The legacy of Fūjin and Raijin will continue to move forward — flowing, changing, and inspiring people, just like the wind and thunder themselves.