Takemikazuchi-no-Kami: The Warrior God Who Shaped Japan’s Myths and Culture

A god born from a blade.

A being who embodies thunder itself.

A warrior so powerful that even other gods hesitated before him.

Do you know his name?

He is Takemikazuchi-no Kami — the God of Thunder, the God of the Sword, and the deity of unshakable courage.

He is the flash of lightning, the cutting force of a divine blade, and the fearless spirit that has inspired warriors for centuries.

What kinds of legends surround him?

And how is he honored in Japan today?

Let us step into the world of this legendary warrior god.

Together, we will explore his power, his stories, and the presence he continues to hold in Japanese culture.

Who Is Takemikazuchi-no Kami?

Before diving into his dramatic myths, let’s begin with a simple introduction to Takemikazuchi-no Kami and the many roles he plays in Japanese belief.

A Brief Profile of Takemikazuchi-no Kami

Takemikazuchi-no Kami (建御雷神) is a powerful and dynamic deity who appears throughout Japan’s ancient stories.

He embodies the force of thunder, the sharp power of the divine sword, and the courageous spirit that protects both warriors and communities.

Here is a simple overview of his main roles:

| Role | Description |

|---|---|

| God of the Sword | Born from the divine blade that struck down the fire god Kagutsuchi. Closely connected with sacred swords such as the Totsuka-no-Tsurugi and the Futsu-no-Mitama-no-Tsurugi. |

| God of Thunder | His nature is compared to lightning — seen by ancient people as a heavenly blade slicing through the sky. |

| Ancestral God of Sumo | Famous for overpowering Takeminakata in the Land Transfer myth, a contest often regarded as the origin of sumo wrestling. |

| Warrior and Martial Deity | Revered by samurai and later by martial artists as a protector who grants courage, strength, and victory. |

| Earthquake-Controlling Deity | Believed to subdue a giant catfish beneath Japan using the sacred Kaname-ishi (Keystone), preventing destructive earthquakes. |

These roles—spanning thunder, swords, earthquakes, sumo, and martial bravery — show just how deeply Takemikazuchi-no Kami is woven into Japanese mythology.

From ancient interpretations of nature to beliefs that remain today, he remains a deity who captures the imagination and spirit of Japan.

Takemikazuchi-no Kami in Japan Today

So how is Takemikazuchi-no Kami viewed in modern Japan?

In Shinto tradition, he is honored as a god of martial arts, courage, and decisive victory.

Athletes, martial artists, and students visit his shrines to pray for strength, focus, and success in moments that truly matter.

Because he once served as the guardian deity of the influential Fujiwara clan, he is also connected to wishes for national peace and stability.

In certain regions, he is enshrined as a protector of local communities, watching over their safety and prosperity.

Over time, his blessings have expanded far beyond the battlefield. Today, people pray to him for:

- Academic success and entrance exams

- Successful negotiations or important decisions

These are seen as modern forms of “victory” in everyday life.

In this way, Takemikazuchi-no Kami continues to stand as a guardian who offers strength when it is needed most — whether in moments of combat, personal struggle, or the pursuit of one’s goals.

Mythological Episodes

Now that we’ve explored Takemikazuchi-no Kami’s background, let’s look at two famous legends that highlight his strength, dignity, and role in shaping Japan’s earliest stories.

The Land Transfer Myth (Kuni-Yuzuri)

One of the most iconic tales involving Takemikazuchi-no Kami shows his authority as a heavenly envoy.

According to ancient mythology, the heavenly gods wished for the land of Japan to be guided by the descendants of the sun goddess Amaterasu, bringing harmony between heaven and earth.

To carry out this divine mission, they sent Takemikazuchi.

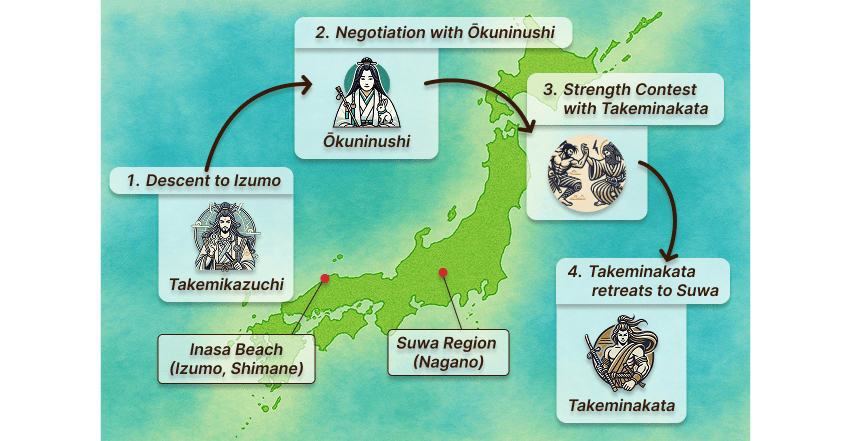

He descended to the shores of Inasa Beach in Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) and confronted Ōkuninushi, the ruler of the earthly realm.

To show his overwhelming authority, Takemikazuchi drew the Totsuka-no-Tsurugi — the legendary “sword of ten hand spans” — plunged it into the cresting waves, and calmly sat upon its blade.

This striking image demonstrated that he had come as more than a messenger—he had come with divine power.

Ōkuninushi hesitated and turned the decision over to his sons.

One son agreed to accept heavenly rule, but the other — Takeminakata — challenged Takemikazuchi to a contest of strength.

The result was swift and decisive.

Takemikazuchi crushed Takeminakata’s arm as easily as bending a young reed and hurled him away.

Defeated, Takeminakata fled to the region of Suwa (Nagano Prefecture), where he vowed to remain.

This dramatic struggle is remembered as the mythological origin of sumo, a tradition still cherished in Japan today.

More importantly, the episode established Takemikazuchi-no Kami as a god of unshakable strength and victory, securing the land for the heavenly descendants.

The Eastern Conquest and the Sword of Futsu-no-Mitama

Another important appearance of Takemikazuchi-no Kami occurs in the myth of Emperor Jimmu’s Eastern Conquest, the story of Japan’s first emperor.

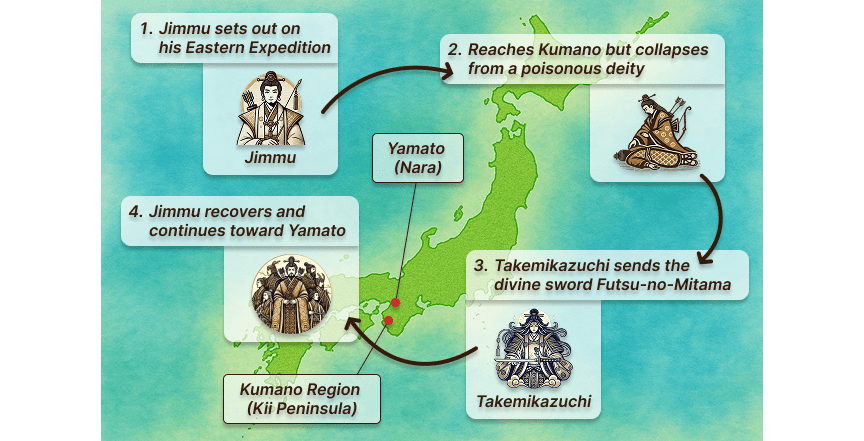

As Jimmu (then called Kamuyamato Iwarebiko) journeyed east to claim the throne and establish his rule in Yamato (Nara Prefecture), he and his army reached the land of the Kumano region in the Kii Peninsula.

There, they were overwhelmed by the poisonous breath of a fearsome deity and collapsed, seemingly on the brink of defeat.

At this critical moment, Takemikazuchi intervened — not by descending himself, but by sending a sacred weapon.

He bestowed the Futsu-no-Mitama-no-Tsurugi, a divine sword infused with his spirit.

With the sword’s power, the evil force was subdued.

Jimmu and his soldiers regained their strength and continued their march toward unifying the land.

Takemikazuchi’s choice not to appear directly is meaningful: it suggests he wished for Jimmu to win through his own resolve, supported — but not overshadowed — by divine guidance.

This episode not only preserved the life of Japan’s first emperor but also portrays Takemikazuchi as a god who offers weapons of protection, decisive strength, and support in moments of greatest need.

Legends in the Landscape: Earthquakes, Catfish, and Thunder

Takemikazuchi-no Kami’s stories are not limited to Japan’s creation myths.

Some of his legends are woven directly into the land itself — especially in legends connected with earthquakes — stories that still echo in Japan today.

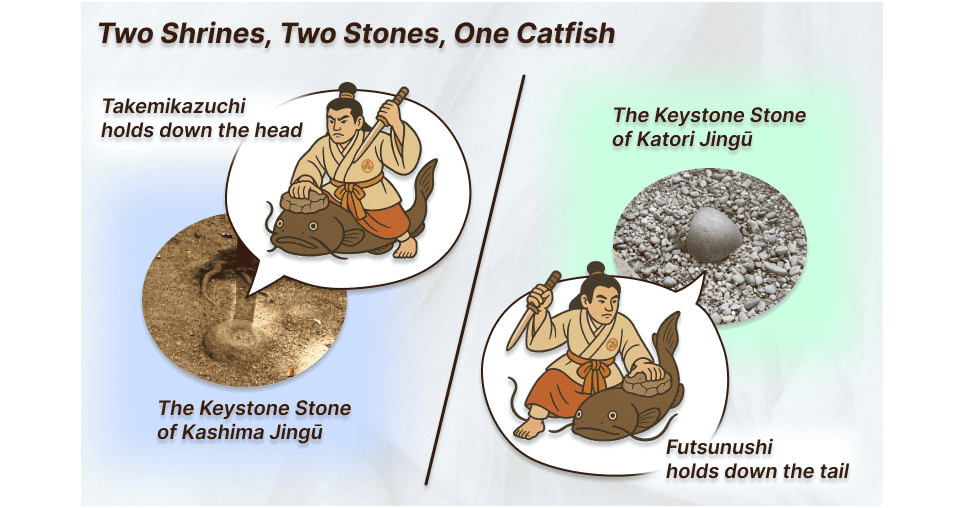

The Keystone Stones and the Giant Catfish

After the Land Transfer myth, it is said that Takemikazuchi and Futsunushi-no-Kami traveled eastward to the provinces of Hitachi (Ibaraki Prefecture) and Shimōsa (part of Chiba Prefecture), regions known in ancient times for frequent tremors.

People believed that earthquakes were caused by a giant catfish (Ōnamazu) living beneath the earth.

To keep this creature from thrashing about, the two gods drove sacred stone pillars deep into the ground, pinning the catfish in place.

These stones became known as Kaname-ishi, or “Keystone Stones.”

The stone at Kashima Jingū in Ibaraki Prefecture is said to press down on the catfish’s head, while the one at Katori Jingū in Chiba Prefecture is believed to hold down its tail.

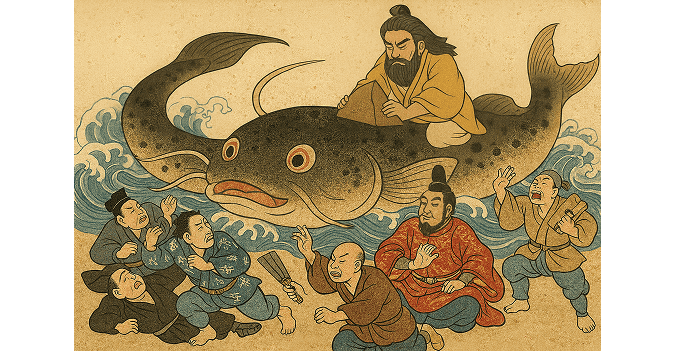

Edo-Era Fears and the Namazu-e Prints

Centuries later, earthquakes continued to be one of the most feared natural disasters in Japan.

During the Edo period, the phrase “jishin, kaminari, kaji, oyaji” — “earthquakes, lightning, fire, and fathers” — listed the forces people dreaded most in everyday life.

At the same time, colorful ukiyo-e known as namazu-e, or “catfish prints,” became widely popular.

These images often depicted the giant catfish believed to cause earthquakes, along with the gods thought to restrain it.

Many namazu-e illustrations show Takemikazuchi-no Kami himself firmly pressing down the catfish, reinforcing his image as a divine protector who keeps disasters at bay.

Note: Many people in Japan today still know the phrase “jishin, kaminari, kaji, oyaji” simply because it has a catchy rhythm.

While earthquakes and fires remain serious concerns today, the four-element expression is remembered mostly as an old saying rather than something people literally fear in everyday life.

Shrines and Worship

Takemikazuchi-no Kami continues to be warmly worshipped across Japan.

Here, let’s look at some of the most significant shrines dedicated to him and the beliefs connected with each one.

Kashima Jingū (Ibaraki Prefecture)

Kashima Jingū is the oldest and most prominent shrine devoted to Takemikazuchi-no Kami.

Here he is honored as the god of martial valor and national protection.

In Japan’s early myths, this region was considered the northern edge of the land, making Kashima an important spiritual guardian of the nation’s frontier.

From the medieval period onward, samurai families worshipped him as their patron deity.

Today, the shrine remains closely associated with victory, martial arts, and success in competitions.

For more details about Kashima Jingū, you can see the English guide here: Kashima Jingū

A small break — a little side note

Would you like to experience a glimpse of the solemn and sacred atmosphere of Kashima Jingū?

This digest video captures the shrine’s serene beauty, surrounded by ancient forests and a deep sense of tranquility.

Around the 1:40 mark, the video also introduces the legendary Kaname-ishi, the “Keystone Stone” said to pin down the giant catfish believed in folklore to cause earthquakes.

The video includes Japanese text captions, but even without reading them, the visuals alone are enough to convey the unique spirit and charm of Kashima Jingū.

Feel free to take a look and enjoy the atmosphere!

Kasuga Taisha (Nara Prefecture)

Kasuga Taisha was founded in 710 CE when the capital moved to Nara and the Fujiwara clan enshrined their ancestral deity—Takemikazuchi—at Mount Mikasa.

According to legend, he arrived riding on a white deer, which became the shrine’s sacred messenger.

Because of this tradition, Nara is still famous for its free-roaming deer today.

As the guardian god of the Fujiwara family, Takemikazuchi became especially linked to prayers for national peace, prosperity, and protection.

For more details about Kasuga Taisha, you can see the English guide here: Kasuga Taisha

Katori Jingū (Chiba Prefecture)

Katori Jingū enshrines Futsunushi-no-Kami, another powerful deity closely connected with Takemikazuchi. In mythology, the two served together as heavenly envoys who helped pacify the land.

For this reason, Kashima (Takemikazuchi) and Katori (Futsunushi) are often regarded as paired centers of martial faith in eastern Japan, deeply respected by warriors through the centuries.

Katori Jingū is widely known for blessings related to victory, protection from misfortune, and traffic safety.

Many visitors also regard Katori Jingū as a place of strong spiritual energy — a place where people come to make firm decisions and strengthen their resolve.

For more details about Katori Jingū, you can see the English guide here: Katori Jingū

Takemikazuchi-no Kami is therefore revered not only as a god of warriors but also as a divine ally who offers strength and guidance when it matters most — whether for individuals, families, or entire communities.

Cultural Significance

Did you know that Takemikazuchi-no Kami is more than just a figure from ancient mythology or shrine tradition? His presence can be found throughout Japanese culture today.

Let’s take a closer look at how Takemikazuchi continues to appear across Japanese culture.

Sumo and the Martial Spirit

One of the most enduring cultural legacies of Takemikazuchi-no Kami is his connection to sumo, Japan’s national sport. Through the myth in which Takemikazuchi overpowers Takeminakata, sumo came to be seen not merely as a sport, but as a sacred contest deeply connected to the divine.

The roof that hangs above the sumo ring (dohyō) is designed in the Shinmei-zukuri style, the same architectural form used in Shinto shrines, emphasizing the sacred nature of the ring itself. Even today, ceremonies such as dedication bouts (hōnō-zumo) are performed at shrines, and newly promoted yokozuna carry out their ring-entering rituals as offerings to the gods.

These enduring traditions show that sumo is a living Shinto ritual that continues to reflect the mythological strength of Takemikazuchi-no Kami.

Modern Appearances in Culture

Takemikazuchi’s influence also reaches far beyond sacred traditions. His name appears widely in contemporary culture, reflecting his lasting image as a symbol of power and protection:

- The mobile game Monster Strike features him as a powerful character.

- In Gundam SEED DESTINY, a large aircraft carrier is named Takemikazuchi.

- A racehorse bearing his name once competed on Japanese tracks.

These examples show how the image of Takemikazuchi-no Kami continues to inspire creators and audiences alike — in games, in anime, and even in sports.

His associations with strength, victory, and a fearless spirit have made him a natural symbol in many areas of modern culture.

In this way, from sacred traditions like sumo to the world of pop culture, Takemikazuchi-no Kami continues to live on as a powerful symbol of strength and steadfast determination for people in Japan.

Conclusion: The Enduring Power of Takemikazuchi-no Kami

From the ancient myths that shaped Japan’s earliest stories, to the sacred rituals of sumo, and even to the familiar symbols found in modern culture, Takemikazuchi-no Kami has long been revered as a deity of strength, courage, and protection.

He is remembered as the god who commands both sword and thunder — one who faces great trials with unwavering resolve, offering strength at decisive moments, from Japan’s first emperor to all who continue to seek victory and guidance today.

Today, he is worshipped at shrines such as Kashima Jingū and Kasuga Taisha, and his presence is felt throughout Japanese culture, extending even into the world of pop culture, where he remains a revered figure.

What Takemikazuchi-no Kami teaches us is that true strength is not merely the power to overcome an opponent, but the ability to guide, protect, and inspire others in times of difficulty.

And so, he continues to bridge the world of myth and the modern age — an enduring symbol of divine strength, courage, and inspiration for generations to come.