Konohanasakuya-hime and Iwanaga-hime: The Myth of Beauty and Mortality

Have you ever wondered why humans grow old? Why every life must one day come to an end?

In Japanese mythology, the answer lies within a single, fateful choice.

Long ago, a divine prince descended from the heavens, and before him stood two sisters — one who offered the gift of eternal life, and the other, the radiance of beauty.

The god made his choice.

And from that moment on, the destiny of humankind was sealed.

What did he choose?

And how did that decision shape the fate of every human to come?

Let us follow this story — a tale of brilliance and impermanence, of lives that shine brightly, only to fade like blossoms in the wind.

Join us as we journey into the ancient myth where Japan’s sense of life, beauty, and mortality first took root.

A Divine Encounter: The Two Sisters of Fate

Before we explore why humans are destined to live brief, beautiful lives, let us begin with the ancient Japanese myth said to have decided the fate of humankind.

The Descent from Heaven and the Blossom Princess

Long ago, in the age of gods, when heaven and earth were still close, the heavenly prince Ninigi-no-Mikoto descended from the High Plain of Heaven to bring harmony to the world below.

This sacred journey—known as the Heavenly Descent (Tenson Kōrin)—marked the beginning of Japan’s divine imperial line.

When Ninigi reached the southern land of Kasasa, he met a maiden whose beauty shone like the blossoms of spring— Konohanasakuya-hime, the Blossom Princess.

Her presence radiated with the grace of spring itself, and Ninigi, captivated at first sight, asked for her hand in marriage.

Her father, the great mountain god Ōyamatsumi, was overjoyed.

To bless this union, he offered not only his gentle daughter Konohanasakuya-hime, but also her elder sister, Iwanaga-hime.

One was as radiant as a flower in full bloom.

The other, as steadfast as the ancient stone.

The Choice that Shaped Humanity

Both sisters were presented to Ninigi as brides, and together they would have given his descendants the gifts of beauty and eternal life.

But Ninigi looked upon Iwanaga-hime and could not accept her solemn, awe-inspiring appearance.

And so, he turned away, choosing only the radiant blossom.

Then the mountain god spoke, his voice echoing through heaven and earth:

"Had you accepted both daughters, your descendants would have lived as enduring as the rocks.

But because you rejected Iwanaga-hime, their lives shall be as brief and delicate as blossoms in the wind."

And so it was.

From that moment, the story says, the fate of humankind was sealed.

The divine bloodline—and all who came after—would know not eternal life, but the beauty and sorrow of mortality.

The Meaning Behind the Myth: Immortality vs. Impermanence

How did you find the story of the moment when humanity’s fate was decided — the tale that marked the beginning of our mortal lives?

In this section, let us look deeper into the meaning behind it.

Beyond the gods and their choices lies something more.

Stone and Blossom: Two Divine Symbols

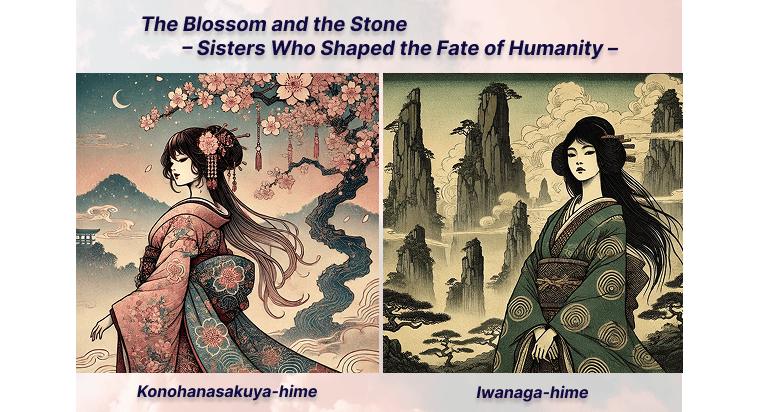

At the heart of this myth stand two sisters — Konohanasakuya-hime and Iwanaga-hime.

They are the key to understanding this story, representing two opposing yet intertwined forces: the eternal and the ephemeral, expressed through the symbols of blossom and stone.

Let us take a closer look at each.

-

Iwanaga-hime — The Long Rock Princess

A symbol of enduring strength and permanence.

Unchanging, timeless, and unyielding like stone — a divine promise of everlasting life. -

Konohanasakuya-hime — The Blossom Princess

A symbol of delicate beauty and fleeting life.

Radiant in full bloom, yet destined to scatter like spring blossoms in the wind — a divine promise of transient brilliance.

When viewed together, these two sisters are far more than characters in an ancient tale.

They reflect the two ideals we humans long for: eternal life and radiant beauty.

Through them, the myth becomes a mirror — one that reveals the delicate balance between endurance and fragility, strength and grace.

A Choice with Philosophical Meaning

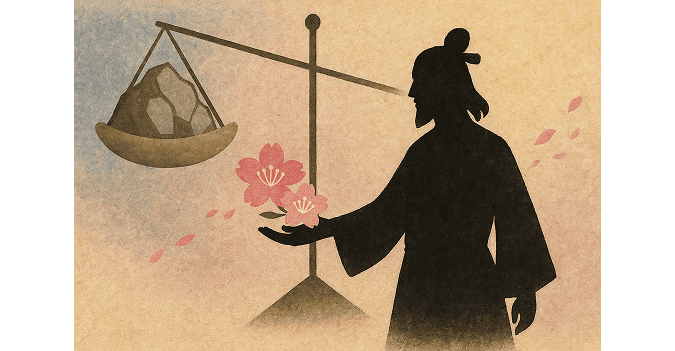

The decision made by Ninigi-no-Mikoto when choosing between the two sisters is one of the most meaningful moments in this story.

It was not a matter of preference or desire.

His choice — to accept beauty while turning away from eternal life — carries a profound message about what it means to be human.

Think about our own lives.

In youth, we are strong, radiant, and full of energy.

But as the years pass, we age, we weaken, and eventually, our time comes to an end.

This, too, is the path Ninigi chose for us—the path of fleeting beauty over unending existence.

His decision shaped not only the destiny of the gods’ descendants, but the very nature of human life itself.

Through this myth, we see a philosophy that still speaks to us today.

It teaches that to live is not only to accept impermanence, but to recognize that beauty shines brightest because it is fleeting.

Because life does not last forever, we must find meaning and beauty within the time we are given.

Taken together, in the story of Ninigi and the two contrasting sisters, we find a reflection of the distance between human ideals and the reality of life — and the meaning that lies within it.

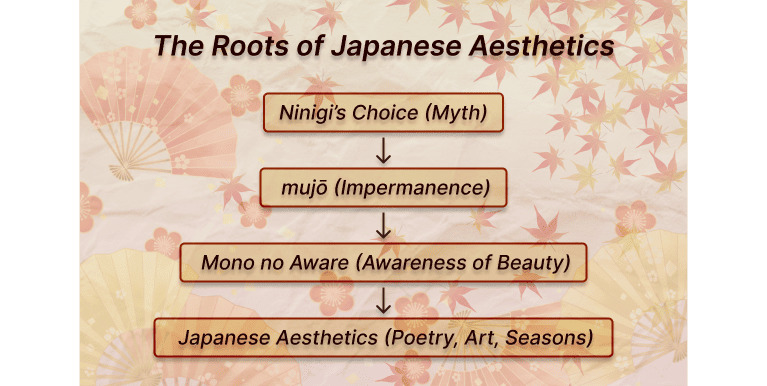

The Roots of Japanese Aesthetics

Did you know that the lessons and values within this ancient myth continued to live on far beyond its time?

They shaped not only how life and death were understood, but also the very foundation of Japanese culture and aesthetics that would endure for centuries.

The idea that beauty is fleeting and life itself is finite gradually came to be linked with the belief that all things are impermanent — mujō (無常) — which became one of the defining foundations of Japan’s unique sense of beauty.

Throughout history, it has been reflected in poetry, painting, and seasonal traditions, inviting people to savor each passing moment rather than mourn its loss.

In later generations, this way of seeing the world further evolved into what became known as mono no aware (物の哀れ) — a gentle awareness of the sadness and beauty that coexist in all things.

It is a concept unique to Japan, yet one that began to take shape in the myths of the gods.

From stories like this one, the sorrow of impermanence and the beauty of life’s radiance are not seen as opposites, but as companions walking hand in hand.

To feel the transience of life deeply is itself an act of compassion.

In this way, Ninigi-no-Mikoto’s decision — which came to shape the very foundation of Japan’s aesthetic sensibility — was far more than a mere legend.

It planted the seed of a worldview that finds beauty in accepting impermanence, and finds something sacred in every falling petal.

Even today, in the fleeting bloom of cherry blossoms or the gentle fading of autumn leaves, the echo of that ancient choice still lingers quietly within the Japanese heart.

A Unique Perspective on Mortality: Japan and the World

Perhaps in your own culture, too, there are myths or folktales that try to explain why human life must come to an end.

Here, let us take a closer look at how different cultures — and Japan in particular — have understood the meaning of life and death.

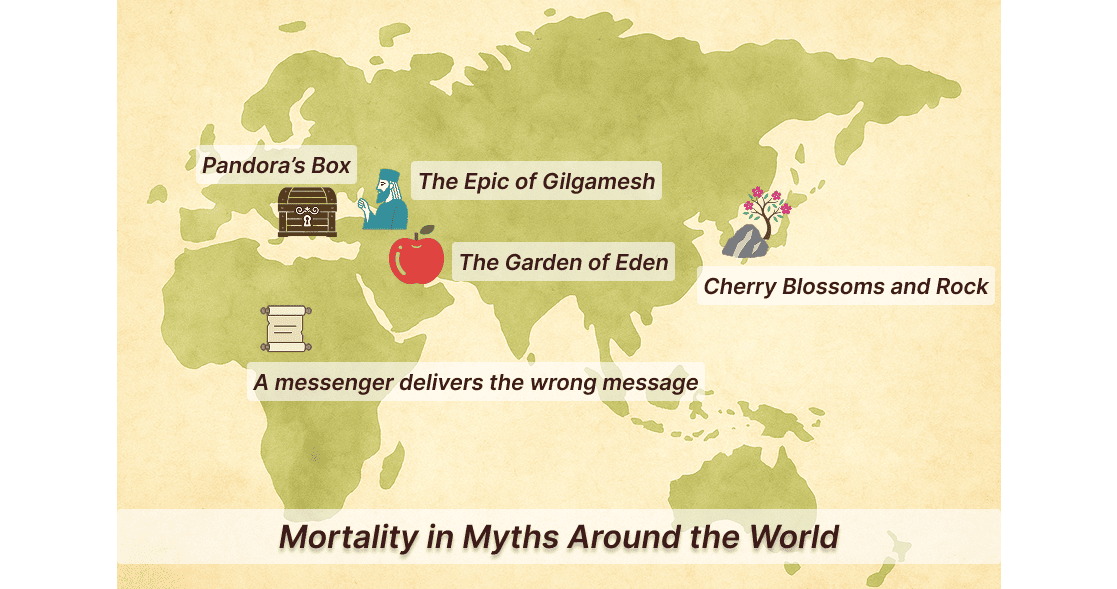

Mortality in Myths Around the World

Across the world, many traditions tell stories about the origin of human mortality — each offering a glimpse into how different cultures understand life, death, and divine will.

Let’s take a look at some of the most well-known examples.

| Culture / Myth | Story or Belief | View of Mortality |

|---|---|---|

| Biblical (Western) | The Garden of Eden — Adam and Eve eat the forbidden fruit. | Death is a punishment for disobedience. |

| Greek Mythology | Pandora’s Box — Pandora opens a forbidden jar, releasing all evils into the world. | Mortality is a consequence of human curiosity and divine retribution. |

| African Folklore | A messenger delivers the wrong message, bringing death instead of eternal life. | Death is a mistake — an accident in divine communication. |

| Mesopotamian Epic | The Epic of Gilgamesh — a hero seeks immortality but ultimately fails. | Mortality is a lesson in acceptance and human limitation. |

Across these myths, death is often portrayed as something tragic — a punishment, a loss, or a mistake that separated humankind from eternity.

Japan’s View: Death as a Conscious Choice

When we compare Japan’s mythology with those from other parts of the world, one striking difference becomes clear.

In Japanese mythology, death is neither a punishment nor a tragedy.

Here, “death” is seen as the result of a deliberate choice — a choice that values beauty, vitality, and impermanence over eternal life.

When Ninigi turned away from Iwanaga-hime, he was not cursed by the gods.

Rather, his decision simply defined the nature of human existence itself — finite, fragile, and yet deeply meaningful.

While other myths warn or mourn, this story gently shines light on the meaning of mortality.

It transforms the loss of immortality into a timeless lesson — that because life does not last forever, we must learn how to live more fully within the time we are given.

In the end, Japan’s myth teaches not to fear the limits of life, but to live within them — finding grace in every moment that fades.

Legacy: From Myth to Modern Japan

The story of this myth continues to echo quietly in Japan even today.

Let us take a brief look at how its legacy has lived on through the generations that followed.

After the events of the myth, Konohanasakuya-hime married Ninigi-no-Mikoto, becoming the divine mother of Japan’s sacred imperial line.

Her son, Hoori-no-Mikoto, is said to be the ancestor of Emperor Jimmu, Japan’s first emperor.

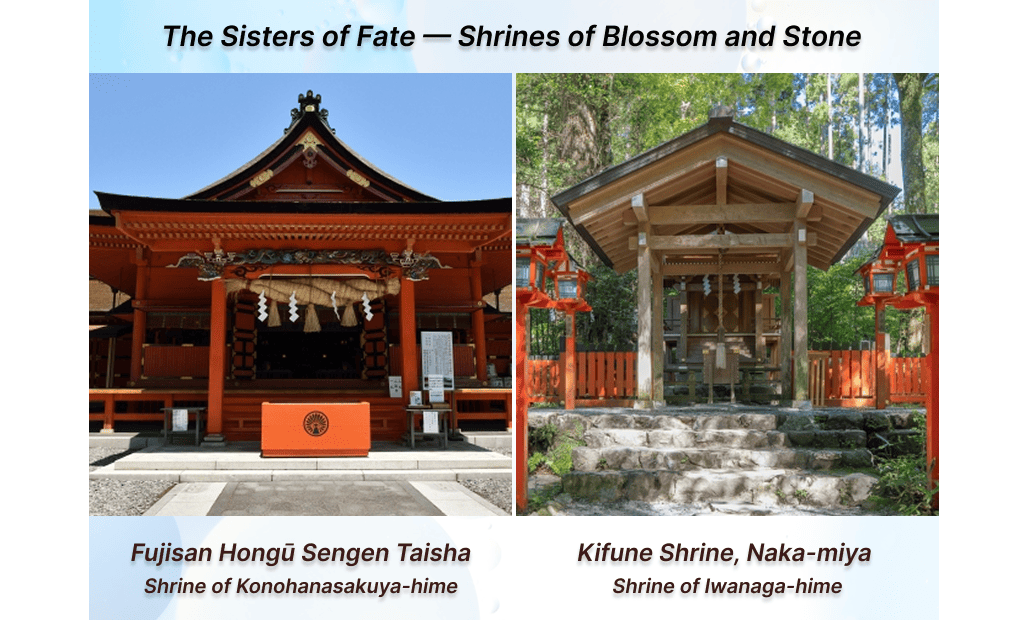

Today, Konohanasakuya-hime is enshrined at Fujisan Hongū Sengen Taisha and countless other shrines across Japan, revered as the guardian goddess of volcanoes, safe childbirth, and the changing beauty of the four seasons.

Iwanaga-hime, on the other hand, though rejected in the myth, was never forgotten by the people of Japan.

She continues to live on as a symbol of strength, longevity, and the quiet endurance of stone.

Her spirit is said to dwell in the mountains, still reflected in traditions that honor resilience and the lasting power of nature.

Through this tale, we see not only a reflection of Japan’s view of life and mortality, but also the divine lineage that shaped its imperial tradition.

Even now, these two contrasting sisters — the gentle blossom and the steadfast stone — are believed to watch over Japan, each carrying her own eternal role within the nation’s spirit.

Conclusion: The Sacred Weight of a Fleeting Life

In the quiet moment when Ninigi turned away from eternity and chose beauty, he made a decision that shaped not only a myth—but the very soul of a culture.

Through this ancient tale, we are reminded that life is not measured by its length, but by its depth.

That even what fades can be sacred.

That impermanence is not a flaw, but a gentle truth—a design that teaches us how to cherish, how to feel, how to live.

In the falling of cherry blossoms, in the aging of our bodies, in the cycle of seasons—we continue to live out this myth.

It is not a story to be mourned, but a story to be lived.

Because the choice that made us mortal also made us human.

And perhaps, in that fragility, we find our greatest strength.