Yomi: Living with the Boundary Between Life and Death

How is death understood in the stories you know?

In Japanese mythology, death is not a place of punishment or judgment.

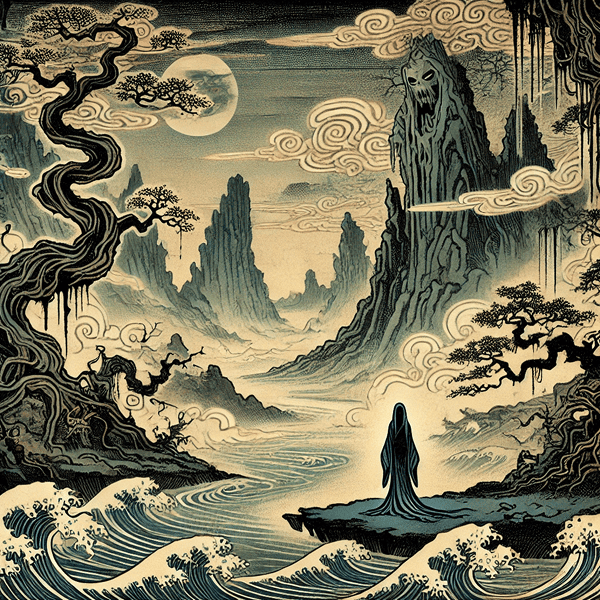

Instead, it is believed to exist as a quiet and separate realm known as Yomi — the land of the dead.

When we lose someone close to us, many of us wish we could see them just once more.

The story of Yomi begins with that very human feeling.

What kind of place is Yomi?

What happens within this hidden world?

Let us gently follow the path to Yomi, the place where life comes to an end.

Together, we will trace the journey of a single god who dared to step beyond the boundary between life and death.

What Is Yomi, the Land of the Dead?

Before exploring the myths in detail, let us first take a gentle look at what Yomi is.

In Japanese mythology, Yomi is the world where the dead reside — the place reached by those whose lives have come to an end.

Yomi is not a realm of punishment, nor a place where souls suffer or are judged.

Instead, it is a separate world connected to the land of the living by a boundary known as Yomotsu Hirasaka, a slope that marks the divide between life and death.

Those who have truly entered Yomi are said to eat the food of that realm.

Through this act, the dead fully become part of Yomi.

From that point on, they live as inhabitants of this shadowed world and cannot return to the land of the living.

Yomi itself is not an evil place, but it is fundamentally different from the world of the living.

It is described as quiet and dim, a land of stillness and decay — a place that the living should not cross into.

A Journey into Yomi: Izanagi’s Descent

From here, let us explore the story connected to Yomi, the land of the dead.

It is a journey shaped by love and loss — the path taken by a single god.

Exploring the Myth of Yomi

The story begins with the creator god Izanagi, who is faced with the death of his beloved wife, Izanami.

Izanami lost her life after giving birth to Kagutsuchi, the god of fire.

The flames burned her body, and the wounds proved fatal.

Unable to bear the grief of losing the one he loved, Izanagi made a desperate decision — he would go to Yomi and bring Izanami back.

What kind of journey awaits him beyond the boundary between life and death?

A Promise in the Darkness

Izanami was gone, yet Izanagi could not accept her absence.

“I must see her again,” he said.

“Even once more.”

Believing that Izanami had not completely faded from existence, Izanagi set out for Yomi, the shadowed land where the dead dwell — a realm standing apart from the world of the living.

At the boundary of that quiet world, Izanagi called out for his beloved wife.

“Izanami… my beloved wife.

Come back with me.

The land we created together still needs you.”

From within Yomi, Izanami answered him.

“My beloved Izanagi,” she replied,

“it is too late for me to return as I once was.”

She told him that she had already eaten the food of Yomi, and through this act had become part of the world of the dead.

Yet she was moved by Izanagi’s devotion.

“Wait here,” she said.

“I will speak with the gods of Yomi.

If they allow it, I may return with you.”

There was only one condition.

“Do not look at me while you wait.”

Trusting her words, Izanagi agreed.

But time passed, and doubt crept into his heart.

His longing grew stronger than his patience.

Unable to endure the waiting any longer, Izanagi snapped a tooth from his comb and lit it — a small flame that would reveal what should never be seen.

The Forbidden Sight

The flame Izanagi had lit made his wife’s form clearer than before.

What he saw was no longer the Izanami who had once lived in the world of the living.

Her body had changed completely, bearing the marks of death and decay.

It was a sight that should never have been revealed to the living.

Izanagi stood frozen in shock.

The promise he had once made echoed in his heart, and in that instant, he understood what he had done.

Seeing herself exposed, Izanami cried out in anguish.

"You have shamed me," she said.

"Why did you look upon me in this state?"

Her sorrow turned into rage.

The boundary between life and death had been broken.

At that moment, fear took over.

Not the fear of death itself, but the fear of what could never be undone.

Izanagi turned and fled from Yomi, his chest tight with terror and regret.

The Birth of Life and Death

As Izanagi ran, the forces of Yomi closed in behind him.

He cast away the ornaments he wore, each one transforming into obstacles that slowed his pursuers.

Without turning back, he ran on while swinging the sword he carried behind him.

Izanagi reached the slope known as Yomotsu Hirasaka, the boundary between the world of the living and the land of the dead.

There, growing at the foot of the slope, he found ripe peaches.

Grasping them, Izanagi turned and hurled the fruit toward those who pursued him, and the power of the peaches drove the forces of Yomi back.

At last, Izanami herself came after Izanagi.

Izanagi placed a massive boulder between them, sealing the path from Yomi.

Standing before the closed boundary, he faced his wife one final time.

Izanami spoke first.

"Each day," she declared,

"I will take one thousand lives from your land."

Without hesitation, Izanagi answered.

"Then each day," he replied,

"I will bring forth one thousand five hundred new lives."

With these words, the cycle of human life and death was set.

Loss would never disappear from the world, but neither would birth.

Even in the face of death, life would continue to be born again and again.

Thus, the boundary between life and death was sealed, and the order of the human world was established.

Universal Themes in the Myth of Yomi

What did you think of the story of Yomi?

From here, let us take a closer look at the meanings and symbols woven into this myth.

Together, we will explore what it reveals about life, death, and the human experience.

The Forbidden Gaze and the “Don’t Look” Taboo

One of the most striking moments in the story of Yomi is the scene in which Izanagi looks upon Izanami’s form, despite being warned that he must not do so.

In that single moment, Izanagi’s fate — and the direction of the story itself — is completely transformed.

This kind of narrative is known as the “Don’t Look” taboo, a motif that appears in myths and folktales across many cultures.

-

Greek mythology

Orpheus is allowed to lead his beloved Eurydice out of the underworld, but only on one condition: he must not look back at her until they reach the world of the living.

Overcome by doubt and longing, he turns around — and loses her forever. -

The Hebrew Bible (Old Testament)

In the story of Lot, his family is warned by divine messengers to flee their city without looking back.

When Lot’s wife disobeys this command and turns to look behind her, she is transformed into a pillar of salt.

This recurring pattern — a single prohibition given in exchange for a promise — reflects a deeply human impulse: the desire to break what has been forbidden.

When that impulse leads to an irreversible loss, the story reveals its deeper truth.

In the myth of Yomi, Izanagi’s forbidden gaze serves exactly this purpose.

Through this story, we are gently reminded that death is irreversible, and that the boundary between life and death exists for a reason — a line that even love cannot cross.

From Personal Loss to Cosmic Law

Another profoundly important moment in the myth occurs when Izanami declares that she will take lives each day,

and Izanagi responds by promising to bring forth even more new life.

This exchange invites us to see that while individual human lives are finite, humanity itself continues through the passing of generations.

This way of expressing human continuity is not unique to Japanese mythology.

In many cultures, myths depict great loss, destruction, or even the threat of extinction.

Yet they ultimately affirm that humanity endures beyond such crises.

Well-known examples include:

-

The Biblical Flood

In the story of Noah, the world is destroyed by a great flood, yet humanity survives through a single family.

After the waters recede, life continues, and the future of humankind carries on. -

Greek mythology

After a devastating flood sent by the gods, Deucalion and his wife bring life back into the world.

Their story symbolizes the rebirth of humanity after the brink of extinction.

Across these myths, the continuation of humanity emerges as a shared hope.

Even though individual lives are limited, humanity endures by passing life forward to the next generation and continuing its journey into the future.

Symbols Unique to Japanese Belief

There are still more meanings hidden within the story of Yomi.

Here, we will explore interpretations that are unique to Japanese mythology,

and see how this story expresses ideas shaped by Japan’s own cultural beliefs.

One Flame and the Unseen World

In the myth, Izanagi lights a single flame on his comb in order to see Izanami’s form.

This single flame carries a deep cultural meaning in Japanese belief.

In traditional Japanese thought, a lone flame — known as hitotsu-bi — is considered ominous.

Lighting only one flame is believed to reveal things that should not be seen, or to offer a glimpse into the world beyond the living.

This belief is rooted in the myth itself.

Even today, traces of this belief remain in everyday practice.

At a household Buddhist altar, candles are usually placed in pairs and lit together.

This is thought to avoid the inauspicious nature of a single flame.

In contrast, ghost stories and tests of courage often make deliberate use of one flame.

Such settings echo the ancient idea that a solitary light can open a path to the unseen world and what lies beyond it.

Reversal and the Sword

As Izanagi fled, he swung his sword behind him while running.

This action was not simply an attempt to strike his pursuers.

In Japanese belief, performing an action in reverse of its proper form was thought to carry ritual and symbolic meaning.

A sword is meant to be held forward and used against an opponent who stands before you.

To swing it backward, away from one’s own line of sight, is to invert its intended purpose.

Such a reversal was believed to function as an act of cursing, rather than direct combat.

By fleeing while swinging his sword behind him, Izanagi was performing a ritual act of rejection, meant to sever his connection to the world of the dead.

Peaches and Protection

As Izanagi flees from Yomi, he hurls peaches at the forces pursuing him.

While reading the story, this moment may seem like nothing more than a desperate attempt to slow his escape.

However, this action carries a much deeper symbolic meaning.

In ancient East Asian belief, peaches were thought to possess the power to drive away evil and misfortune.

They were associated with protective energy, capable of repelling harmful and impure forces.

By throwing peaches at the pursuers from Yomi, Izanagi is recognizing them as beings of corruption and death.

At the same time, he is invoking the protective power of the peaches to resist those forces.

What appears at first to be a simple act of survival is, in fact, a symbolic gesture — one that expresses the belief that evil can be confronted and held at bay through sacred protection.

A small break — a little side note

The peaches Izanagi threw while fleeing from Yomi did more than save him in that moment.

As he cast them, he spoke a heartfelt wish:

“If there are others who suffer as I have,

please help them in the same way.”

Moved by this prayer, the peaches became a divine being known as

Ōkamutsumi-no-Mikoto, a god associated with protection and aid for those in distress.

Why not revisit the myth of Yomi through this shadow-play style video, this time focusing on the story of the peach and the compassion behind it?

Where Is Yomi?

After tracing the cultural symbols and hidden meanings within the myth, we begin to see how deeply it reflects the beliefs and worldview of ancient Japan.

As these layers come into focus, a new question naturally arises.

What kind of place did Yomi refer to?

Let’s explore how people in ancient Japan may have understood and envisioned the land of the dead.

Yomi as a Space Close to the Living World

In the myth, Izanagi passes through Yomotsu Hirasaka, reaches the place where Izanami resides, and finally seals the boundary between their worlds with a massive stone.

When these elements are viewed together, they can be seen as closely resembling the structure of a type of ancient Japanese tomb known as a horizontal stone chamber (yokoana-shiki sekishitsu).

These tombs were entered through a narrow passageway, called the corridor, which led to the innermost burial chamber.

The entrance was sealed with a large stone, known as a blocking stone, used to separate the world of the living from the space of the dead.

Seen through this lens:

- Yomotsu Hirasaka corresponds to the tomb’s passageway

- The place where Izanami dwells reflects the innermost burial chamber

- The great stone used to block Yomi mirrors the sealing stone of the tomb itself

In this interpretation, Yomi is not a distant underworld, but a space modeled after the burial chamber where the dead were laid to rest.

Love, Loss, and the Reality of Death

The story of Yomi can be understood as the moment when Izanagi, driven by love, approaches the resting place of his deceased wife and is forced to confront an unchangeable truth — that the dead do not return to life.

The myth grounds itself in a space that lies between life and death.

Through this setting, it expresses a deeply human realization: the painful boundary that exists between love and death.

The pursuit from Yomi may also be read symbolically.

The chasing figures represent grief, longing, and suffering that follow the loss of someone dear.

By fleeing, casting obstacles behind him, and finally sealing the boundary with a massive stone,

Izanagi is not only escaping the land of the dead, but also struggling to sever himself from despair and begin the process of moving forward.

In this way, the myth of Yomi portrays the pain of parting, the weight of memory, and the quiet determination to continue living — even after love has been forever separated by death.

Yomotsu Hirasaka Today: A Place Where the Myth Lives On

The story of Yomi does not belong only to the distant past.

Even today, there is a real place where the presence of this ancient myth can still be felt.

In Shimane Prefecture, there is a site known as Yomotsu Hirasaka.

It is widely regarded as the boundary between the world of the living and the land of the dead, and has become a well-known destination for visitors drawn by its mythological significance.

The path of Yomotsu Hirasaka is a gently sloping road surrounded by forest.

Tall trees and scattered rocks line the way, and the dim, quiet atmosphere creates a feeling of distance from everyday life.

On both sides of the path stand stone pillars, connected by a sacred rope (shimenawa), marking the space as a spiritual boundary.

Further ahead, a stone monument can be found, beyond which rest two massive rocks.

These are believed to represent the great stone that Izanagi is said to have pulled into place, sealing the entrance to Yomi and separating the worlds of life and death forever.

For those who feel curious after reading this story, detailed information is available on the official Shimane tourism website:

Yomotsu Hirasaka

Standing on this quiet path, visitors may find themselves reflecting on the boundary between life and death — a boundary that has been imagined here for centuries.

A small break — a little side note

Would you like to see the place believed to be the setting of the myth of Yomi with your own eyes?

This video introduces Yomotsu Hirasaka, long regarded as the boundary between the world of the living and the land of the dead, along with Iya Shrine, a site deeply connected to this sacred landscape.

The quiet, solemn atmosphere of the shrine and the awe-inspiring presence of Yomotsu Hirasaka create a powerful sense of reverence.

Take a moment to experience the world of Yomi as it exists today — a place where ancient stories still echo in silence.

Conclusion: Living with the Boundary Between Life and Death

The myth of Yomi is not simply a story about gods and the land of the dead.

It reflects how people in ancient Japan understood life, death, and the boundary between them.

Through Izanagi’s journey, the myth teaches that death is irreversible, and that love alone cannot cross the line separating the living from the dead.

At the same time, it reminds us that the end of a single life does not mean the end of humanity.

Through succession and renewal, life continues, generations follow one another, and the world moves forward.

Within this story is the quiet hope of ancient people — a wish that humanity would endure, be passed on, and continue to flourish, even in a world where loss is inevitable.

In this way, the myth of Yomi speaks not only about the gods, but about human love and loss, separation and acceptance, and the calm resolve to keep living in a world where death is an unavoidable part of life.

Rather than denying the sorrow that comes with the end of life, the myth acknowledges it.

It teaches that while grief and pain cannot be avoided, finding the strength to let go, face forward, and continue walking is itself an essential part of a meaningful life.