The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter: The Story of Princess Kaguya and Her Lasting Inspiration

A glowing bamboo. A princess from the Moon. A love story destined to fade.

Welcome to the world of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (Taketori Monogatari)—Japan’s oldest tale. For more than a thousand years, this story has fascinated readers with its blend of wonder, romance, and heartbreak.

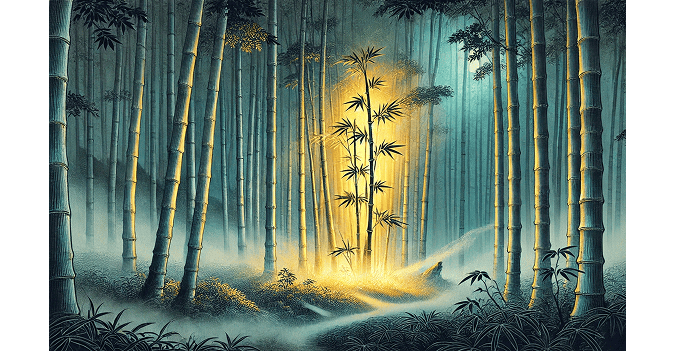

Imagine a bamboo grove glowing in the night, a princess who shines like moonlight, and a sky that opens to take her home. Doesn’t it feel like stepping into a world of fantasy and mystery? This timeless legend has inspired countless works of art, literature, and film—and it continues to capture hearts all around the world.

So, let’s begin our journey. Step into the bamboo forest with me, uncover the tale’s origins and hidden meanings, and discover why the story of Kaguya-hime still shines bright after a thousand years.

Plot Summary: The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter

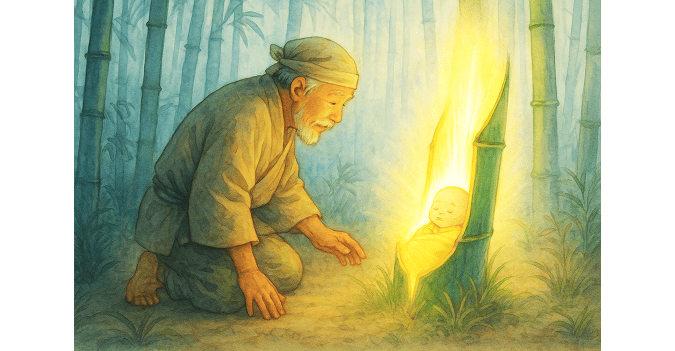

A long, long time ago, an old bamboo cutter was walking through the forest when he noticed one stalk of bamboo was glowing softly, almost like a lantern. Curious, he cut it open— and inside was a tiny girl, no bigger than his hand, her skin shining like moonlight.

"Oh my! What a wondrous child!"

he whispered.

He hurried home, and together with his wife they decided to raise her as their own. They named her Kaguya-hime—the Shining Princess.

As the years passed, Kaguya-hime grew into a young woman of such beauty that people said,

"Surely she is not of this world!"

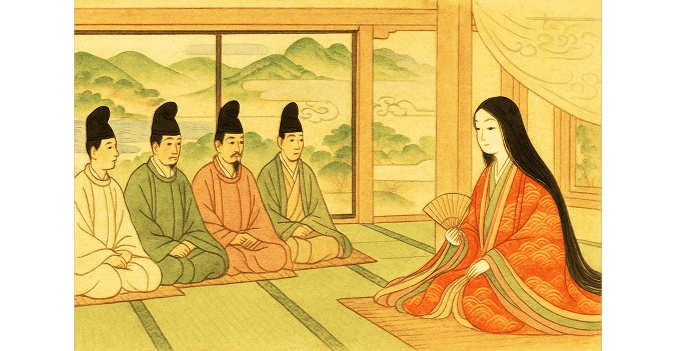

Soon noblemen from every corner of the land came to ask for her hand in marriage.

But Kaguya-hime only smiled gently and said,

"If you truly wish to marry me, then bring me a treasure the world has never seen."

She gave each man an impossible quest: to bring back the Buddha’s Stone Bowl, the Jeweled Branch from Mount Hōrai, a robe woven from fire-rat fur, a shining jewel from a dragon’s neck, and a shell born from a swallow—treasures that could only exist in legends.

The suitors tried their best, but one by one their tricks were uncovered. The men went home in shame.

Even the Emperor of Japan himself came to visit her.

"I have never seen such beauty,"

he confessed.

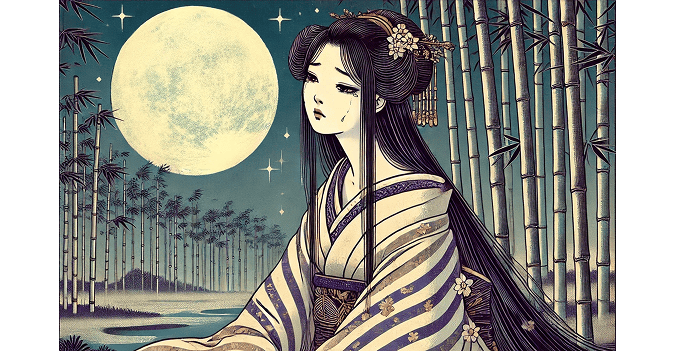

As the months passed, a shadow fell over Kaguya-hime’s radiant smile. She often gazed up at the full moon, her eyes filling with tears.

"My dear child, why do you weep so?"

asked the old bamboo cutter. At last, Kaguya-hime confessed in sorrow,

"The time has come… I was born not of this world, but of the Moon." Soon, they will come to take me home.

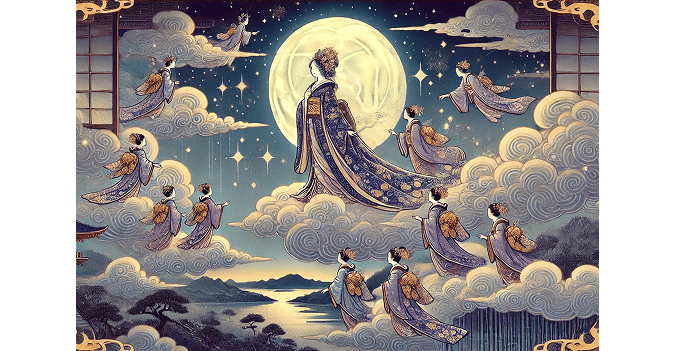

On a night when the full moon shone silver, the sky opened. A procession of heavenly beings descended, their robes glowing like starlight. Kaguya-hime, dressed in a radiant robe of light, rose into the heavens.

Before leaving, she sent a letter and a small vial of the elixir of immortality to the Emperor. Yet in his grief, he said,

"What use is eternity without her?"

He ordered the elixir burned atop Japan’s highest mountain. The smoke, they say, still rises from Mount Fuji, reaching up toward the Moon where Kaguya-hime now dwells.

A small break — a little side note

This video features the famous opening passage of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, read aloud in its original classical Japanese (kobun).

It may surprise you, but modern Japanese people can’t automatically understand this old form of the language. That’s why it’s still taught in school as part of classical literature.

Through passages like this, students get a glimpse into the words and culture of people who lived centuries ago.

In fact, many schools even give a memorization test on these very lines!

I remember learning and memorizing them myself—and even now, I can still recall the rhythm of those opening words:

「今は昔、竹取の翁といふ者ありけり…」

“ima ha mukashi, taketori-no-okina to iumono arikeri...”

Cultural and Historical Background

You’ve just walked through the story of Kaguya-hime—how did it feel? From here, let’s take a closer look at the culture and history of Japan that shaped and inspired this timeless legend.

Origins of the Story

Who exactly created this story?

The truth is—we don’t really know. The author’s name has been lost to time, and sadly no original manuscript has survived. The versions we read today are copies, the oldest of which were written down much later, in the Muromachi period (14th–15th century).

But that doesn’t mean we know nothing. Scholars believe the tale was first composed over a thousand years ago, in the early Heian period (794–1185). Although the author’s identity is unknown, certain clues give us a picture of who he might have been:

- An educated man living near the imperial capital of Heian-kyō (present-day Kyoto)

- Familiar with Chinese classics, Buddhism, and the newly invented kana script

- Someone who enjoyed waka poetry—short, elegant verses beloved by Heian nobles

- Wealthy enough to afford the fine paper on which the story was written

The tale also pokes fun at the powerful families of the time, especially the Fujiwara clan who controlled politics.

Because of this, many scholars think the author was someone on the outside of their influence—close enough to observe, but free enough to criticize.

The Heian World and Its Influence

The tale also opens a window into the daily life and culture of the time. So what kind of society was Japan’s Heian period?

In terms of art and literature, it was truly a “golden age.” This was the era when Japan’s own unique culture blossomed—aristocrats lived in splendid palaces, wore elegant robes, and spent nights under the moon composing poetry.

Yet at the same time, Heian society was strict and appearance-focused. Marriages were often arranged not for love, but for status and political power.

In such a world, a woman like Kaguya-hime—who rejected not only noblemen but even the Emperor himself—was quietly bold.

Her refusals can be read as a gentle challenge to the values of her time.

Symbolism in the Tale

The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter is filled with symbols woven into its story.

Let’s take a look at some of the most important motifs that give the tale its deeper meaning:

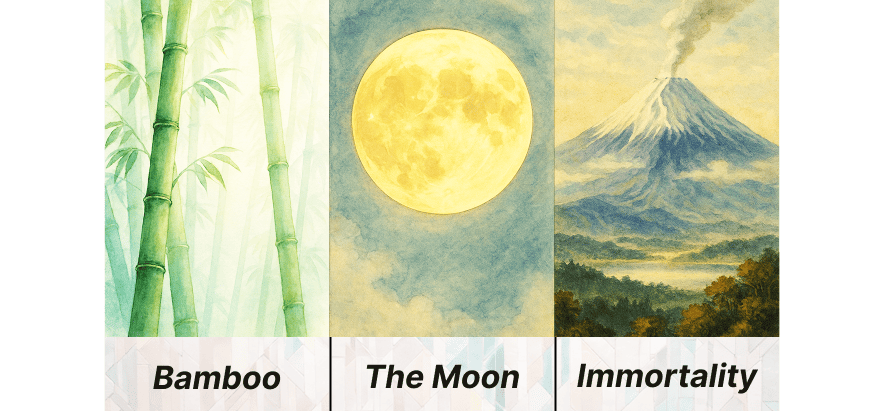

| Symbol | Meaning | In the Tale |

|---|---|---|

| Bamboo (竹) | Purity, resilience, renewal | Its hollow core suggested spiritual openness, and its fast growth symbolized new life. Kaguya-hime’s birth from a glowing bamboo stalk linked her to nature’s mystery and blessing. |

| The Moon (月) | Beauty, longing, unreachable ideal | In East Asian tradition, the moon represents an otherworldly perfection. For Kaguya-hime, it is both her true home and the destiny she cannot escape. |

| Immortality (不老不死) | Eternal life, contrasted with impermanence | The elixir of immortality reflects Chinese and Japanese legends. When the Emperor burns it atop Mount Fuji, it symbolizes the Buddhist idea of impermanence—reminding us that mortal love is more precious than eternal life. |

Through these symbols, the story reflects both the refined tastes of the Heian court and timeless human emotions—love, longing, and the pain of letting go.

Timeless Themes and Lasting Appeal

The true charm of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter lies in how it reflects human emotions that never fade and the cultural values of the society that created it.

Even though it was written over a thousand years ago, its themes still feel fresh and relevant today.

So let’s take a closer look at what makes this story timeless.

The Beauty of Impermanence

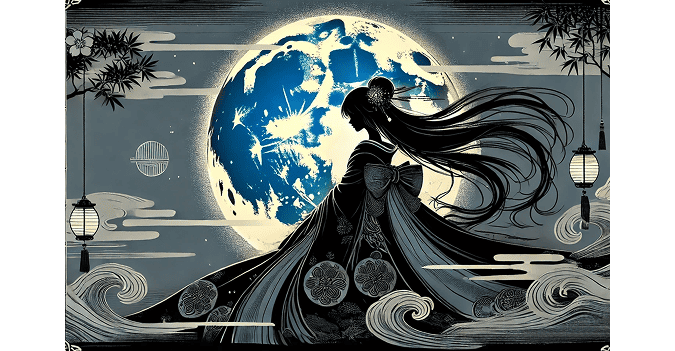

In Japanese aesthetics, there is a concept called mono no aware—the gentle awareness of life’s fleeting beauty. Kaguya-hime’s short time on Earth, her radiant presence, and her inevitable return to the Moon remind us that no matter how precious something is, it cannot last forever.

But this impermanence is not only to be mourned—it is also to be embraced. This acceptance is the essence of mono no aware: finding beauty in the transient nature of life itself. Through this lens, loss is transformed from pure tragedy into something bittersweet, touching hearts in a uniquely tender way.

Human Desire and the Folly of Ambition

The impossible trials given to Kaguya-hime’s suitors are not heroic quests, but playful lessons about vanity and pride. Each man sought glory, yet in the end, their failures were revealed for all to see.

The tale teaches us that status and ambition can blind us, while true worth lies elsewhere. It is a reminder of values that remain just as important today as they were a thousand years ago.

Between Two Worlds

Kaguya-hime belongs to two realms: the Moon, perfect but distant, and the Earth, imperfect yet full of human warmth. Her life is shaped by this tension between the world she longs for and the world where love holds her.

In the end, she must return to the Moon—even though it means leaving behind those who loved her most. This reflects a universal struggle: the pull between our personal desires and the fates we cannot change.

It is a story of living between two worlds—a feeling that still resonates with anyone who has ever faced the choice between heart and duty.

Why It Still Captivates

So why does this story continue to shine after more than a thousand years? Because it speaks to both Japanese values—love of nature, beauty, and a quiet acceptance of life’s impermanence—and to universal truths that touch people everywhere.

It tells of love and separation, longing and loss, and the fleeting beauty of moments that cannot last. And perhaps that is why, even now, the tale of Kaguya-hime feels as radiant as the Moon itself—distant, yet always shining in our hearts.

Modern Adaptations and Influence

More than a millennium later, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter still echoes—shaping popular culture, the performing arts, and even science. So where can we still find traces of Kaguya-hime today? Let’s take a closer look.

Direct Retellings of the Tale

Studio Ghibli’s Masterpiece

Perhaps the most famous modern retelling is Studio Ghibli’s 2013 film The Tale of the Princess Kaguya, directed by Isao Takahata. It is remarkable that a story written more than a thousand years ago could still draw such attention that one of Japan’s most famous animation studios chose to bring it to life on screen. With its hand-drawn watercolor style and emotional depth, the film introduced the tale to audiences worldwide and even received an Academy Award nomination.

Ballet and Traditional Theater

The stage has embraced Kaguya-hime’s story. She even appeared in kabuki theater, where her tale was transformed into a vibrant performance that connected Japan’s oldest story with one of its most traditional art forms.

More recently, in 2023, the Japan Performing Arts Foundation presented a full-length ballet production of Kaguyahime, blending classical dance with the timeless legend and bringing it to life once again in an entirely new medium.

Works Inspired by Kaguya-hime

Modern Anime Inspirations

The legend has also inspired playful references in modern works. For example, the hit manga and anime series Kaguya-sama: Love Is War not only borrows its heroine’s name but also mirrors the qualities of the moon princess herself. In the story, Kaguya Shinomiya is portrayed as a true genius—gifted in the arts, music, academics, and even martial skills—an almost flawless character who reigns as the school’s untouchable beauty. This “brilliantly perfect” image overlaps with the legendary Kaguya-hime, whose unmatched charm drew noblemen and even the Emperor to her side.

A small break — a little side note

The heroine of this worldwide hit anime, Kaguya Shinomiya, is a brilliant and talented girl admired by all—almost like the real Moon Princess herself. But here’s the twist: while she’s perfect in every way, she’s absolutely hopeless when it comes to love!

What follows is a hilarious and heart-throbbing battle of romance between her and the student council president, Miyuki Shirogane. Set in their elite high school, the story mixes comedy, drama, and sweet romance in a way that has captured fans across the globe.

It’s fun, easy to follow, and full of charm—so why not start by enjoying the theme song?

Science and Space Exploration

The legend has even reached into science. In 2007, Japan’s space agency JAXA launched a lunar orbiter named Kaguya (SELENE) in honor of the moon princess. It was a poetic gesture—linking Japan’s oldest story about the Moon with humanity’s most advanced exploration of it.

Through the image of the Moon and Princess Kaguya, the contrast between an ancient tale and cutting-edge technology becomes striking—and deeply inspiring.

Legends and Symbolic Treasures

The legends hidden within The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter are many and varied. Among them, two stand out as the most famous: the five impossible treasures sought by Kaguya-hime’s suitors and the elixir of immortality she left behind. Let’s uncover the secrets behind these mysterious symbols.

The Impossible Treasures

Kaguya-hime’s five noble suitors were each sent on a quest for five treasures so rare they could only exist in legend. Each of these treasures carried its own symbolic meaning. Let’s take a look at what they represent.

| Treasure | Description | Symbolism |

|---|---|---|

| The Buddha’s Stone Bowl (仏の御石の鉢) | Said to be a sacred relic used by the Buddha himself, carved from miraculous stone. | Spiritual purity and unattainable holiness |

| The Jeweled Branch of Mount Hōrai (蓬萊の玉の枝) | A branch from the mythical island of immortals, with silver roots, a golden trunk, and blossoms of pearls. | Immortality and the unreachable paradise |

| The Robe of the Fire-Rat (火鼠の皮衣) | A cloth woven from the fur of a legendary fire-rat, impossible to burn. | Protection, resilience, and the allure of the impossible |

| The Jewel from a Dragon’s Neck (龍の首の珠) | A radiant pearl guarded fiercely by a dragon. | Courage, danger, and the cost of ambition |

| The Shell Born from a Swallow (燕の産んだ子安貝) | A mythical shell laid like an egg by a swallow, believed to bring fertility and good fortune. | Life, blessing, and rarity beyond reach |

None of these treasures truly exist. Each reflects values and ideals—purity, immortality, courage, and fortune—that humans long for but can never fully obtain. In this way, these treasures symbolize an ideal of perfection that can never truly be obtained— and in doing so, they serve as a metaphor for Kaguya-hime herself.

The Elixir of Immortality and Mount Fuji

In the story, the Emperor was given the elixir of immortality by Kaguya-hime, but in the end he commanded that it be burned at the summit of Mount Fuji. And within this story lies a legend about how the mountain gained its name. Some say that Fuji (富士), meaning “everlasting abundance,” comes from a wordplay with fushi (不死), which means “immortality” or “never dying.”

And so, the tale ends by saying that the smoke from the burning elixir still rises from Japan’s highest mountain all the way to the Moon. This reflects the reality of the time when the story was created—Mount Fuji was an active volcano, its smoke visible in the sky. Today the eruptions have ceased, and many climbers now visit Mount Fuji, but it remains a living volcano. In this way, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter also reminds us of Japan’s natural history.

Conclusion: Beauty in What Cannot Last

For more than a thousand years, The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter has lived on—not only as Japan’s oldest surviving story, but as a work that continues to speak to the heart. It blends myth and human truth, weaving together beauty, longing, and the inevitability of parting.

Through Kaguya-hime’s brief but radiant life on Earth, the tale reflects the Japanese appreciation for impermanence and the bittersweet nature of love. The story stirs the same emotions in us today as it did centuries ago: wonder, sorrow, and a quiet acceptance of life’s passing moments.

In the end, Kaguya-hime reminds us that what is most beautiful is often what we cannot keep. And perhaps that is why, even now, her story continues to rise like the Moon—distant, yet eternally shining in our hearts.