The Sensu: Unfolding the Beauty, History, and Spirit of Japan

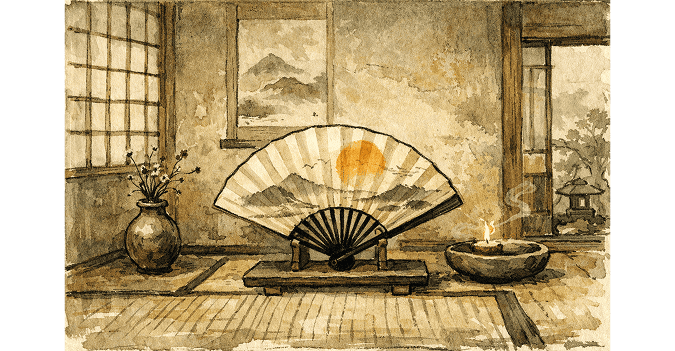

Have you ever felt a soft breeze in your hand, as if you were holding a small work of art?

That is the quiet joy a Japanese sensu — the folding fan — can offer.

At first glance, it might seem like nothing more than a simple way to cool off on a hot day. But when you open it with a gentle motion, a whole world unfolds.

Inside that spreading fan live art, good fortune, and history — all carefully folded together. Each sensu carries Japan’s sense of beauty, shaped by time and tradition, waiting to be discovered.

So what kind of culture is hidden within a sensu?

And why has it continued to be loved for centuries, even in today’s modern world?

Let’s begin a journey into the story of the Japanese folding fan — a miniature masterpiece filled with elegance, symbolism, and enduring charm.

What Is a Sensu?

Before we dive deeper, let’s begin with a simple overview of what a sensu actually is.

A Folding Fan That Creates a Gentle Breeze

A sensu is a traditional Japanese tool held in one hand and gently waved to create a soft breeze.

It is a type of folding fan, carefully designed to open and close smoothly with simple, graceful movements.

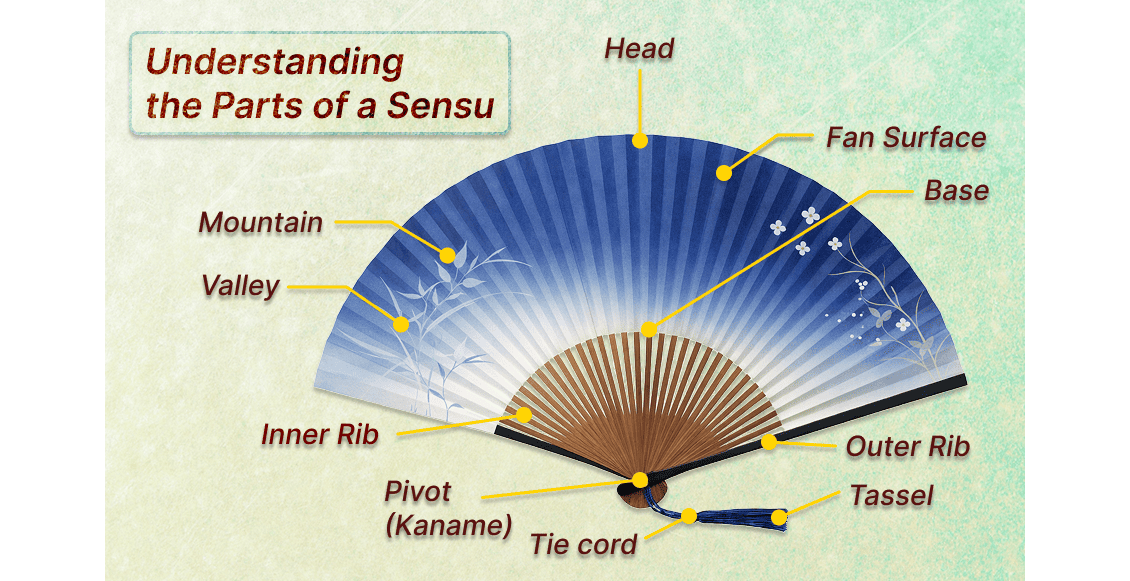

Structure: Ribs, Pivot, and the Fan Surface

A sensu is constructed by gathering several to dozens of thin ribs, typically made from bamboo or wood.

These ribs are fixed together at one end, forming a single pivot point known as the kaname.

Though small, this pivot plays an essential role—it allows the fan to open and close smoothly and effortlessly.

In most cases, paper is attached to the ribs, forming the fan’s surface.

When the sensu is opened, this paper spreads outward into a fan shape, creating airflow while drawing an elegant arc.

At the same time, the fan surface becomes a canvas for decoration.

Traditional patterns, paintings, and calligraphy are often applied here, transforming a practical object into a miniature work of art.

The Charm of the Sensu: Compact, Graceful, and Practical

One of the sensu’s most appealing features is its ability to fold into a compact form when not in use.

This makes it easy to carry, which is why many people have long used it to keep cool during Japan’s hot summer months.

Opening and closing a sensu is also part of its quiet charm.

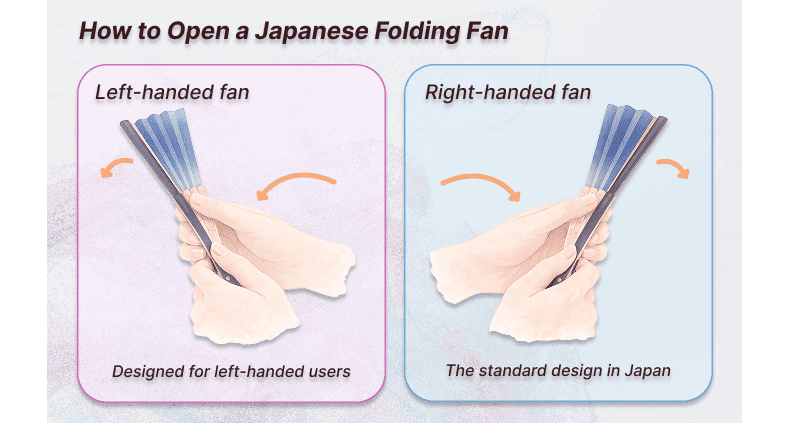

Most sensu are designed for right-handed use and are typically opened by gently pushing the ribs outward with the right thumb.

Some people open them by lightly flicking or waving the fan itself, enjoying the smooth, effortless motion.

While right-handed designs are standard, left-handed sensu are also available, reflecting the thoughtful attention given even to small details.

Together, this balance of portability, ease of use, and graceful movement is what makes the sensu not just practical, but deeply satisfying to use.

Simple in structure yet elegant in motion, the sensu reflects Japan’s thoughtful approach to everyday design—where beauty, function, and care quietly come together.

Origins and History Part I – The Birth of the Sensu

The sensu has a long and fascinating history, stretching back nearly 1,200 years to ancient Japan.

In this first part, we explore the earliest stages of that journey — from the birth of the folding fan to the period when it became an essential cultural object within the imperial court and classical arts.

Early Japan: The Birth of the Folding Fan

The oldest known form of the Japanese folding fan dates back to the Nara period (710–794).

This earliest type was known as the hiōgi (檜扇), and archaeological evidence confirms its existence. Notably, examples of hiōgi have been discovered at the site of Prince Nagaya’s former residence.

The hiōgi was crafted by binding together thin wooden slats—most commonly cypress.

These slats were fastened at the pivot point using twisted paper cords made from washi, while the upper part was often reinforced with decorative cords such as silk threads.

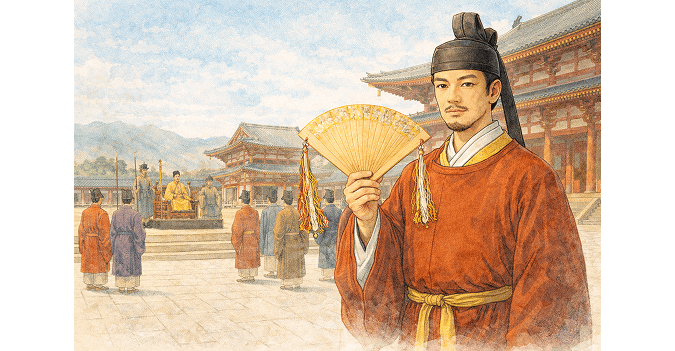

At this stage, however, the hiōgi was not a tool for creating a breeze.

Instead, it functioned primarily as a ceremonial object, closely connected to court rituals and official duties. Hiōgi were often used to record notes related to ceremonial procedures or protocols, rather than for practical comfort.

Although the hiōgi introduced the essential concept of a foldable fan—an invention fundamental to later sensu—its role remained largely formal and symbolic.

Heian Period: The Rise of the Kawahori-ōgi

A major transformation in the history of the folding fan occurred during the Heian period (794–1185) with the emergence of the kawahori-ōgi (蝙蝠扇).

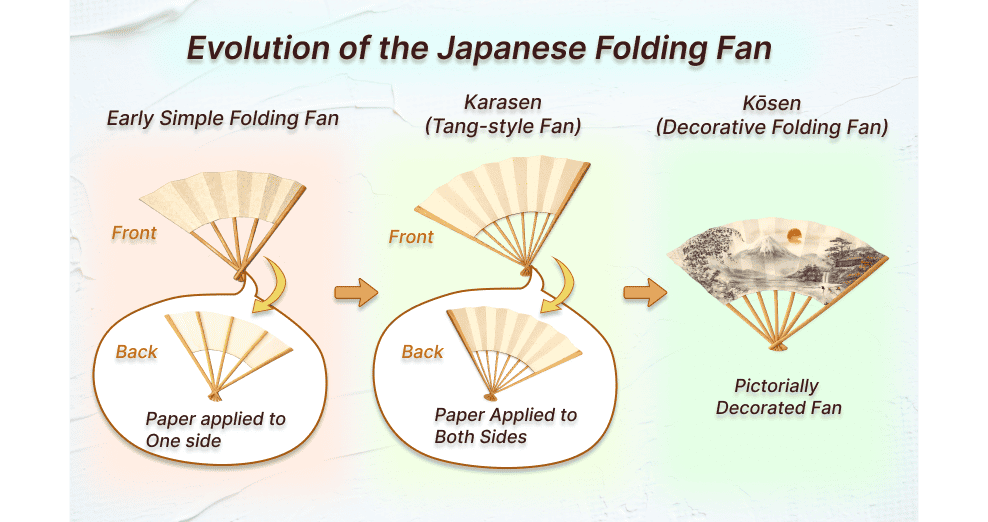

The kawahori-ōgi incorporated paper attached to slender ribs, making it significantly lighter and more flexible. At this stage, paper was typically attached to only one side of the ribs, with the reverse side left exposed.

This innovation allowed the fan to produce airflow efficiently, turning it into a practical tool for daily life. According to legend, its shape was inspired by the wings of a bat, and it is traditionally linked to the semi-mythical Empress Jingū.

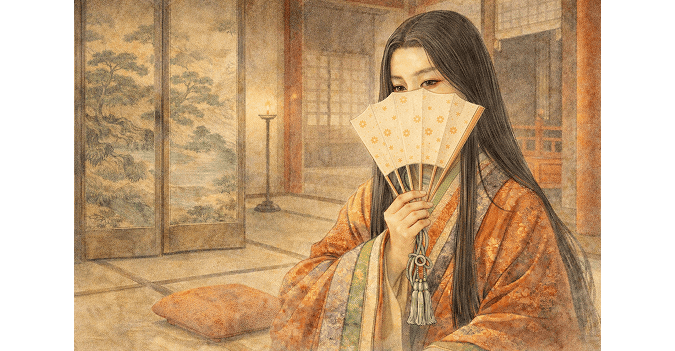

With the spread of the kawahori-ōgi, folding fans were first widely used for cooling, and soon began to take on additional roles beyond simply creating a breeze.

In the refined society of the Heian court, they were used to conceal facial expressions, exchange poems such as waka, or present flowers—subtle gestures of communication and etiquette vividly described in works like The Tale of Genji.

During this period, the folding fan became an essential part of aristocratic life, valued not only for its function but also for its role in social interaction and aesthetic expression.

Muromachi Period: From Practical Tool to Art Form

As Japanese society changed, so did the role of the folding fan.

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), new influences from abroad brought fresh ideas and techniques.

One such influence was the introduction of a fan style known as karasen (“Tang-style fan”), which featured paper attached to both sides of the ribs.

Japanese artisans studied this design and adapted it to local tastes, transforming it into decorative fans known as kōsen.

These fans were often painted with distinctly Japanese motifs, reflecting seasonal beauty, landscapes, and cultural symbols.

Through this process, the folding fan evolved beyond a simple everyday object and became a medium of artistic expression.

By the end of the Muromachi period, the sensu had already become an essential cultural tool — firmly established in classical performing arts such as Noh and in ceremonial practices related to early forms of tea gatherings.

Its widespread use in everyday life, however, would come later, during the Edo period.

Origins and History Part II – From Everyday Life to Global Culture

From the Edo period onward, the sensu became a familiar companion in everyday life, while also beginning a journey beyond Japan in search of new forms of expression.

In this second part, we explore how the folding fan spread through society, crossed cultures, and continued to evolve into the modern age.

Edo Period: A Fan for Everyone

By the Edo period (1603–1868), the sensu had become a familiar part of everyday life in Japan.

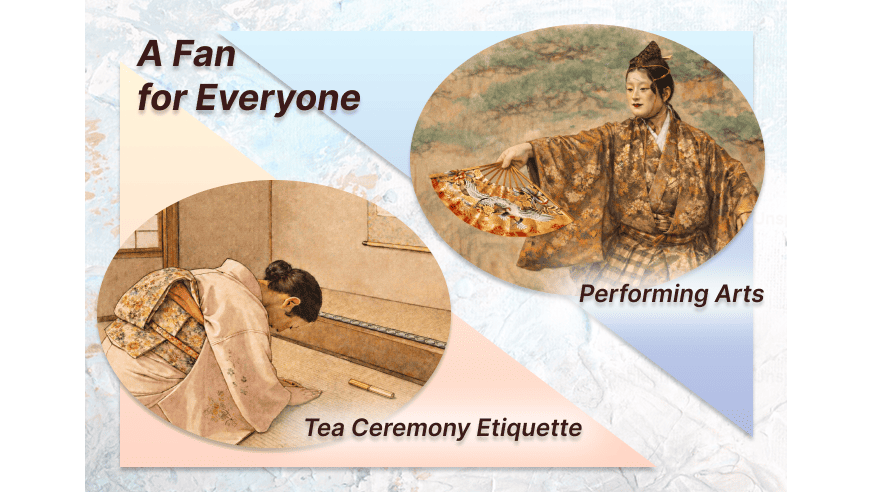

Folding fans were widely used by townspeople and had become essential tools in established cultural practices such as Noh, Kyōgen, and the tea ceremony.

At the same time, advances in production techniques and the growth of urban culture brought significant changes to how fans were made and distributed.

In addition to traditional centers like Kyoto, new hubs of fan craftsmanship emerged in Edo (modern-day Tokyo).

As a result, sensu became more affordable and easier to obtain, allowing people from all social classes to carry them as practical seasonal accessories.

It was during this period that the sensu truly became the most common and stylish way to stay cool during Japan’s hot summer months. No longer limited to specific classes or settings, the folding fan had become an item enjoyed by everyone.

To Europe – and Back Again

Even as the sensu became firmly rooted in everyday life in Japan, it was also beginning a journey beyond its borders.

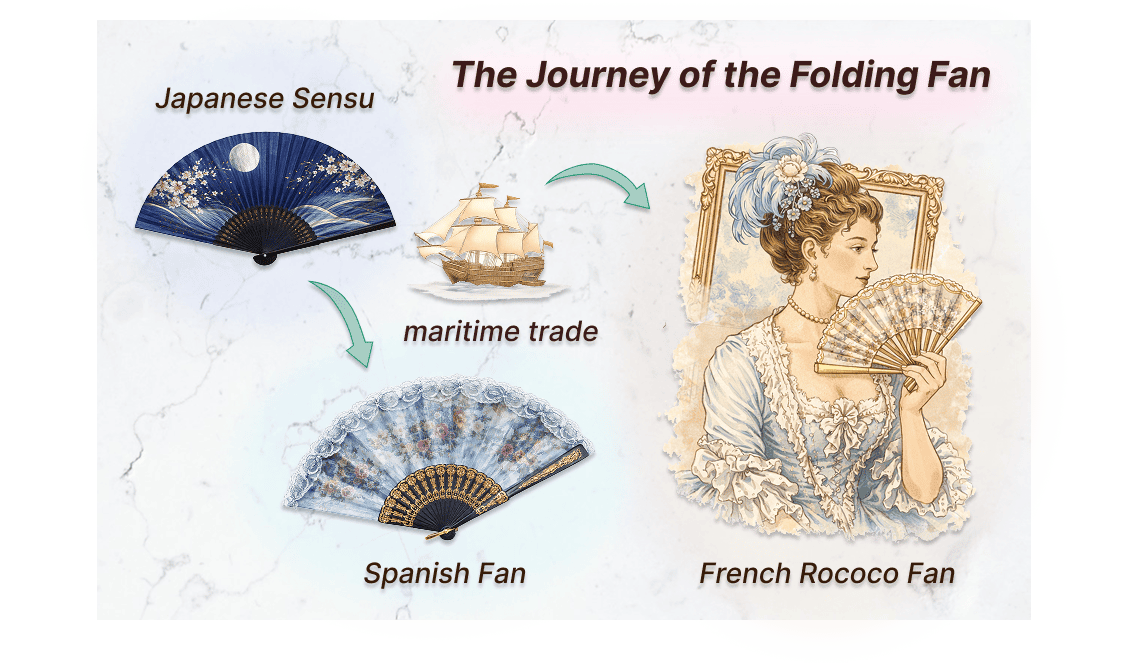

From the 16th century onward, Japanese and Chinese folding fans traveled to Europe through maritime trade routes. They first captured attention in Spain, where they became known as “Spanish fans,” and soon spread across the continent as fashionable accessories for noblewomen.

By the 17th and 18th centuries, European craftsmen began producing their own fans using silk, lace, and even peacock feathers.

France, in particular, became famous for its elegant Rococo-style fans, and people even began using fans as a playful, symbolic way to communicate feelings without words—an unspoken “language of the fan.”

Artists such as Édouard Manet and Berthe Morisot featured fans in their paintings, reflecting both the influence of Japonisme and Europe’s fascination with East Asian beauty.

Reverse Influence: The Return of Western Fans to Japan

In the late 19th century, this cultural exchange came full circle.

European-style fans — richly decorated with paintings, carvings, silk, and lace — made their way back to Japan.

Rather than adopting these foreign fans unchanged, Japanese artisans reinterpreted their materials and aesthetics within the familiar structure of the sensu. This led to the creation of the kinusen, or silk fan, blending Western elegance with Japanese craftsmanship.

Through this process, the folding fan expanded its expressive range once again, bridging Japanese tradition with global artistic influences.

From Stage to Pop Culture: Fans in Modern Japan

The influence of Western-style fans did not stop with craftsmanship.

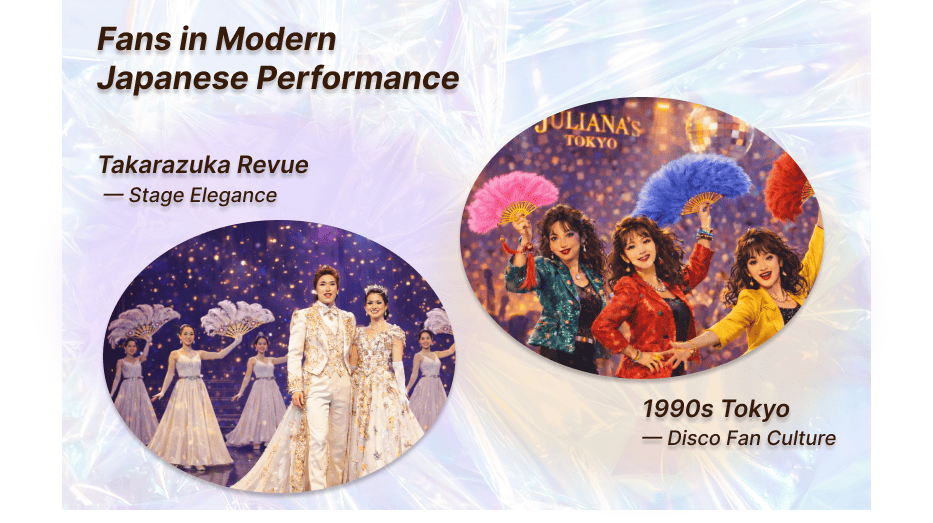

Beginning in 1913, the Takarazuka Revue adopted large, decorative fans as dramatic stage props. Inspired by Western aesthetics, these fans were used to enhance glamorous choreography and theatrical expression.

Decades later, during Japan’s economic bubble of the 1980s and 1990s, fans found yet another role. In discos and nightclubs, flamboyant feathered fans in vivid colors were waved rhythmically as part of dance culture.

These fans later became known as “Juri-sen,” named after the famous nightclub Juliana’s Tokyo, where they became a symbol of vibrant nightlife and pop culture.

In this way, the folding fan has continued to evolve — from court rituals and classical performing arts to popular culture — carrying centuries of tradition while adapting to new forms of expression across different eras and places.

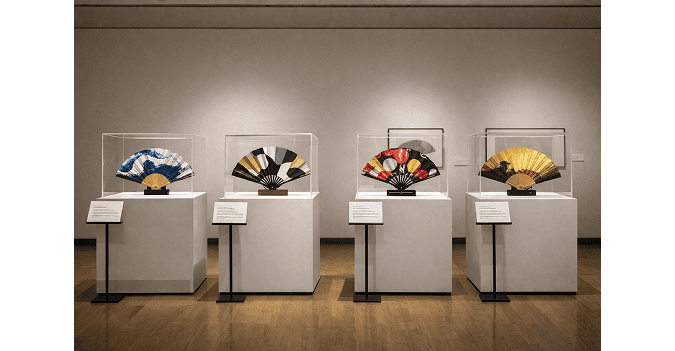

Types of Japanese Folding Fans

Throughout the history of the sensu, many different types of folding fans have appeared and evolved.

In this section, we introduce the main types of sensu that are still made and used today, each shaped by a specific role or tradition.

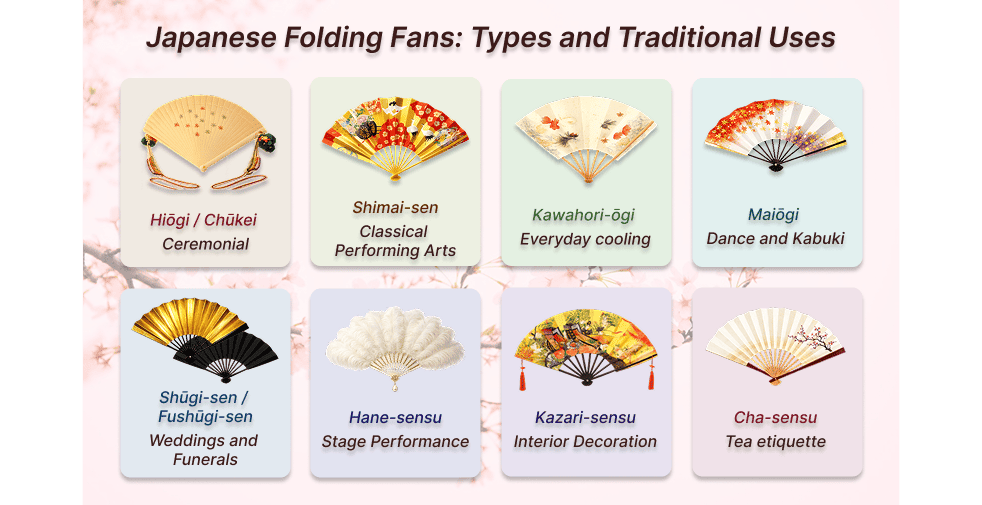

Below is a table summarizing the most representative forms and how they are traditionally used.

| Type | Description | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|

| Hiōgi (檜扇) / Chūkei (中啓) | Wooden folding fans made from thin cypress or bamboo slats. Traditionally used in rituals; chūkei is also used in Noh and other performing arts. | Ceremonial use, traditional performances |

| Shimai-sen (仕舞扇) | Fans made with bamboo ribs and washi paper, used in Noh and Kyōgen. Designs and colors vary by role and performance school. | Classical performing arts |

| Kawahori-ōgi (蝙蝠扇) | Lightweight folding fans with paper or cloth attached to bamboo ribs. Many modern summer fans belong to this category. | Everyday cooling in summer |

| Maiōgi (舞扇) | Stage fans for Japanese dance and Kabuki, often decorated with gold or silver. Both sides share the same design for stage visibility. | Dance, Kabuki, stage performance |

| Shūgi-sen (祝儀扇) / Fushūgi-sen (不祝儀扇) | Formal fans made with decorative paper. White or gold are used for celebrations; black is used for mourning. | Weddings, funerals, formal wear |

| Hane-sensu (羽根扇子) | Feather-adorned fans designed for visual impact, often seen in theatrical productions such as the Takarazuka Revue. | Stage performance, decorative effect |

| Kazari-sensu (飾り扇) | Decorative fans made for display, sometimes opening into a full circular shape. Used as interior ornaments rather than for cooling. | Interior decoration |

| Cha-sensu (茶扇子) | Small bamboo-and-washi fans used in tea settings for formal greetings and etiquette. They are kept closed during use. | Tea practice and etiquette |

As you can see, many different kinds of folding fans still exist in Japan today.

Each type reflects a specific role, tradition, or moment in Japanese life — showing how the sensu has adapted to countless settings while quietly preserving its cultural roots.

Symbolism and Cultural Significance

Did you know that the sensu holds symbolic meaning in Japanese culture, beyond its practical use as a cooling tool?

Let’s take a closer look at the meanings hidden in its shape, patterns, and traditional uses.

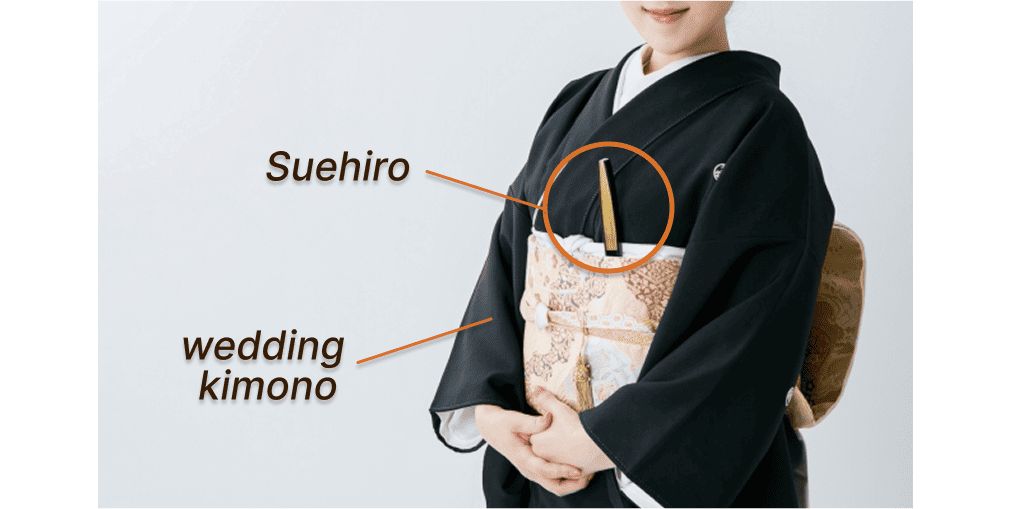

The Shape of Prosperity

A sensu opens outward from its pivot into a wide, fan-shaped form.

In Japanese culture, this expanding shape is called suehirogari (末広がり), symbolizing growth, prosperity, and a hopeful future.

For this reason, sensu have traditionally been used as auspicious objects at celebrations.

The formal fan worn with wedding kimono, for example, is often referred to as suehiro, reflecting this positive symbolism.

A Gift for Every Milestone

Fans have long been cherished as meaningful gifts for life’s important milestones in Japan.

To give a sensu is to offer wishes for prosperity, happiness, and long life.

Common occasions for gifting a sensu include:

- Longevity celebrations, such as kanreki (60th birthday), koki (70), kiju (77), beiju (88), and sotsuju (90).

- Retirement gifts for respected elders or colleagues who have served for many years.

- Graduations, housewarmings, store openings, and coming-of-age ceremonies.

- Children’s milestones, such as Shichi-Go-San, a traditional festival celebrating healthy growth.

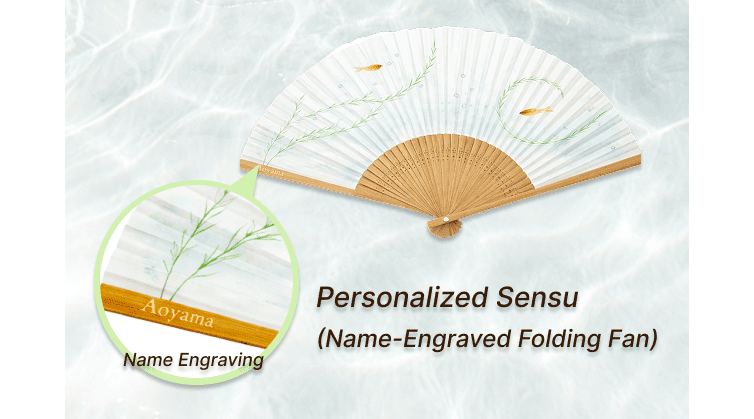

For these special occasions, it is common to choose a personalized fan (naire-sensu), engraved with a name, meaningful phrase, or proverb.

Such fans are especially appreciated as retirement or longevity gifts, where the gesture itself carries deep respect and heartfelt wishes.

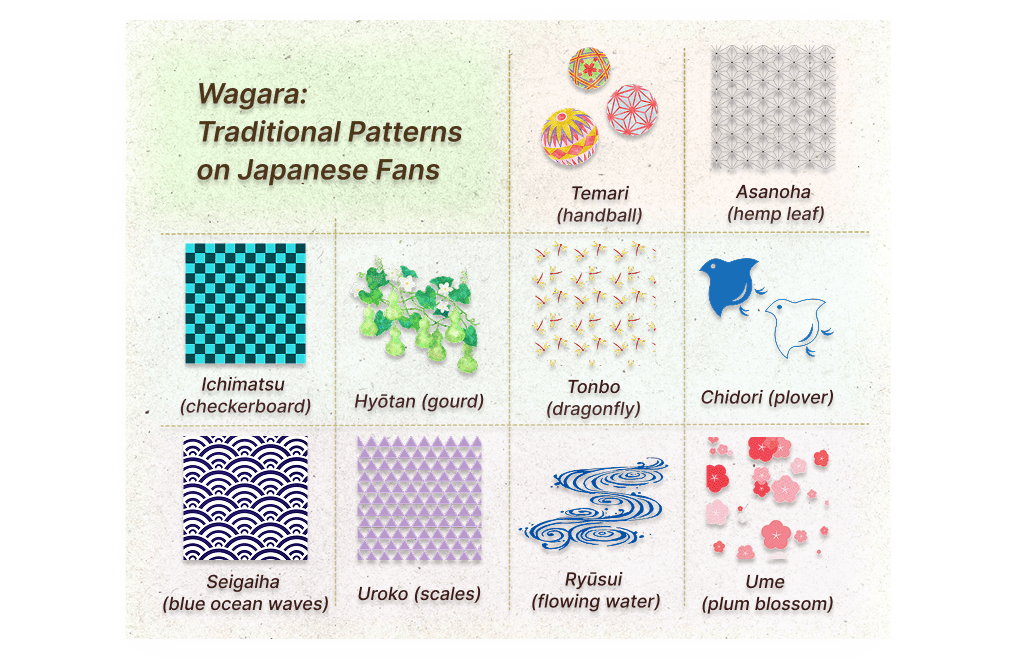

Motifs and Their Meanings

When a sensu is opened, its surface often reveals decorative patterns.

These designs, known in Japan as wagara (和柄), are considered auspicious and each carries its own symbolic meaning.

| Pattern | Japanese Name | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Temari (handball) | 手毬 | Youthful beauty, parental wishes for a child’s healthy growth, and a harmonious family. |

| Asanoha (hemp leaf) | 麻の葉 | Rapid growth, good health, and protection against evil. |

| Ichimatsu (checkerboard) | 市松 | Endless continuity, prosperity, and expansion. |

| Hyōtan (gourd) | 瓢箪 | Fertility, prosperity, good health, and warding off evil. |

| Tonbo (dragonfly) | 蜻蛉 | Victory, courage, and good fortune; a samurai’s symbol of never retreating. |

| Chidori (plover) | 千鳥 | Success and abundance; paired with waves, symbolizes overcoming challenges together. |

| Seigaiha (blue ocean waves) | 青海波 | Eternal peace, happiness, and good fortune. |

| Uroko (scales) | 鱗文様 | Protection from evil and renewal. |

| Ryūsui (flowing water) | 流水文様 | Purification, resilience, and the ability to overcome difficulties. |

| Ume (plum blossom) | 梅小紋 | Perseverance, vitality, and prosperity. |

Through these motifs, a sensu becomes more than a decorative object. Each pattern carries a quiet wish—connecting the person who holds the fan with tradition, symbolism, and good fortune.

Sacred and Ceremonial Significance

Fans have long been used in dances dedicated to the gods, believed to bring good harvests and protect health.

Over time, the fans themselves came to be regarded as sacred objects, closely connected to ritual and formality.

In the tea ceremony, a cha-sensu is placed in front of the knees during greetings to mark a symbolic boundary (kekkai).

This simple gesture expresses respect and helps maintain proper distance between host and guest within the ritual space.

This ceremonial role of the sensu continues even today.

In formal Shinto rituals, members of the Japanese Imperial Family are still seen holding a folding fan as part of their official attire when standing before the gods.

In this context, the fan serves as a symbol of dignity, restraint, and reverence, quietly expressing respect within a sacred setting.

In this way, the sensu is not simply an object used to create a breeze.

It is cherished as a cultural symbol—one that carries blessings and serves as a bridge between everyday life and the sacred.

Artistry and Craftsmanship

Japanese folding fans are known for their delicate and beautiful appearance. But what kind of craftsmanship and ingenuity lie behind that beauty?

In this section, let’s take a closer look at the artistry of the sensu — exploring the knowledge, skill, and thoughtful care of the artisans who bring each fan to life.

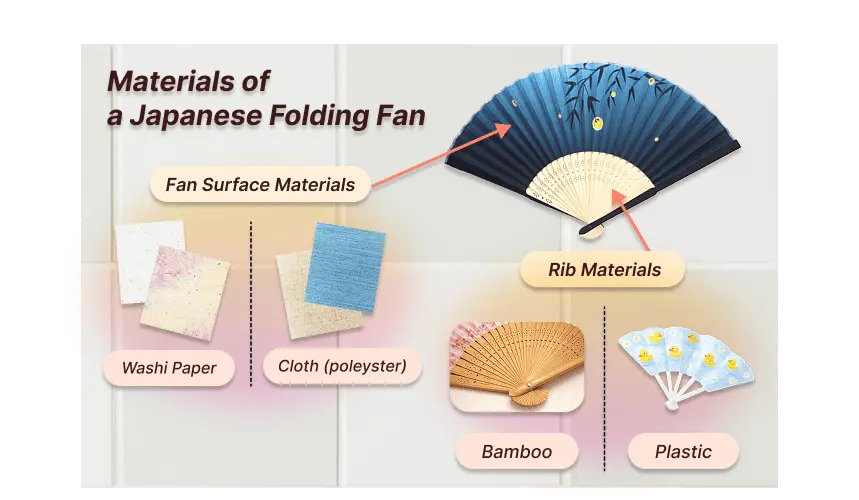

Materials

A Japanese folding fan (sensu) is crafted with great care in its choice of materials.

Its structure is made up of three main parts: the fan surface (senmen), the outer ribs (oyabone), and the inner ribs (nakabone).

The materials selected for each part are chosen with care, affecting not only the fan’s appearance, but also its feel, durability, and airflow.

Below is an overview of the main materials commonly used in sensu and the characteristics of each.

| Part & Material | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Paper (washi) – traditional fan surface | Creates strong airflow; can be decorated on both sides | Vulnerable to moisture |

| Cloth (polyester) – modern fan surface | Water-resistant; suitable for casual use | Produces gentler airflow; often single-sided |

| Bamboo (white, black, or smoked) – traditional ribs | Flexible, durable, and elegant; becomes smoother with use | Natural color variations may occur |

| Plastic – modern ribs | Easy to clean and maintain | Lacks the warmth and character of natural materials |

Traditionally crafted sensu favor washi paper and bamboo for their texture and balance, while modern fans may use polyester or plastic for affordability and everyday convenience.

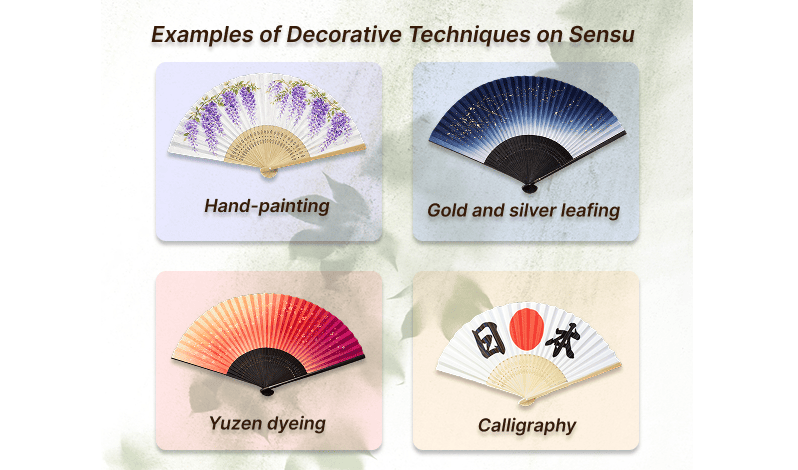

Decorative Techniques

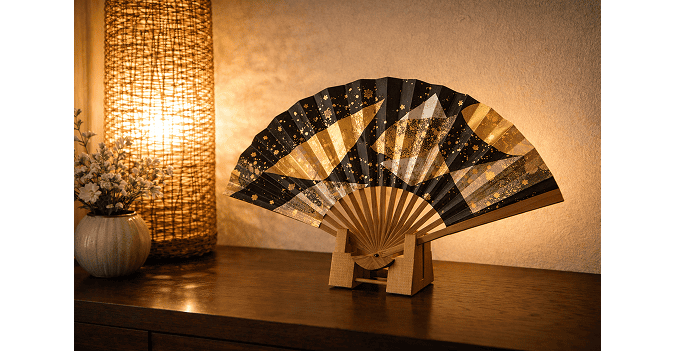

When opened, the surface of a sensu reveals itself as a canvas for Japanese art and cultural expression.

Its decoration calls for refined skill as well as a deep sensitivity to Japan’s seasons and traditions.

Below are some of the main techniques used to decorate Japanese folding fans.

-

Hand-painting – From quiet landscapes to bold seasonal imagery.

Fan painters (senmen eshi) often depict flowers such as cherry blossoms (sakura), wisteria (fuji), and chrysanthemums (kiku), along with celebratory motifs like flower carts (hanaguruma) or phoenixes (hōō). Animals associated with good fortune—horses, hawks, and dragons—are also popular subjects. -

Gold and silver leafing – Adding brilliance and depth.

Artisans apply metal foil using traditional techniques such as hira-oshi (pressed foil sheets), noge (thin cut strips), chigiri-baku (scattered flakes), and sunago (fine foil particles). Each method creates a distinct texture and shimmer that changes with the light. -

Yuzen dyeing – Intricate color through resist-dyeing.

Using methods such as katazome (stencil dyeing), artisans hand-dye silk or washi paper. Kyoto-style yuzen fans, created by certified craftsmen, are especially admired for their layered colors and refined patterns. -

Calligraphy – Words placed with intention.

Poems, proverbs, or classical waka are written so that they flow naturally with the folds of the fan. Care is taken to ensure the text remains hidden when the fan is closed, revealing its message only when fully opened.

The Making Process

How is a sensu assembled after such careful attention to materials and decoration?

Let’s take a brief look at the production process of a Japanese folding fan—a craft that brings together many specialized skills.

- Preparing the ribs – Bamboo or wood is split, shaped, and polished.

- Preparing the paper – Layers of washi are glued together for strength, then dried and cut.

- Decorating the surface – Painting, dyeing, or gilding is applied by hand.

- Folding and shaping – The fan is carefully folded to ensure smooth movement.

- Mounting – The decorated surface is attached to the ribs.

- Finishing touches – Edges are trimmed and the pivot is adjusted for balance.

Depending on the complexity of the design, a single fan may take days or even weeks to complete.

Through this careful process, each sensu becomes more than an accessory—it is a quiet testament to Japanese craftsmanship, where beauty and function are shaped by human hands.

A small break — a little side note

Kyoto is one of Japan’s most renowned centers for traditional folding fans, known as Kyō-sensu.

What makes Kyō-sensu special is its division-of-labor craftsmanship.

Each step—splitting bamboo, preparing paper, painting, folding, and final assembly—is handled by a dedicated artisan who has mastered that single process through years of experience.

Through careful, patient handwork, simple bamboo and paper are transformed into an elegant folding fan, rich with balance, beauty, and quiet refinement.

Watch the process unfold, and you may find that the gentle rhythm of the artisans’ movements is not only mesmerizing — but somehow warms the heart as well.

Fans in Japanese Performing Arts

In modern Japan, a sensu is most commonly used as a practical tool for creating a breeze.

Yet within traditional performing arts, the folding fan continues to carry a meaning far beyond that of a simple prop.

Let us take a closer look at the roles the folding fan continues to play within Japan’s classical performing arts.

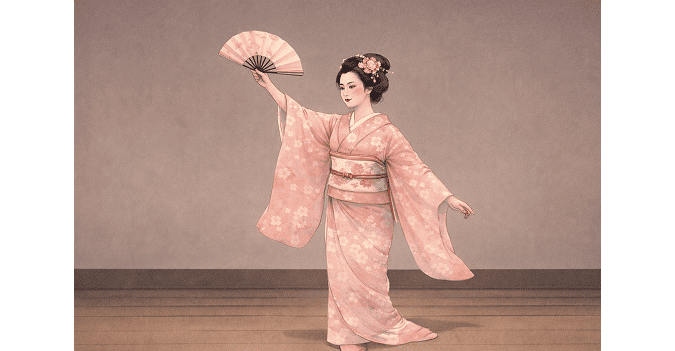

Nihon Buyō (Japanese Dance)

In nihon buyō, the fan plays a central role in choreography and expression.

A gentle opening of the fan may evoke the blooming of cherry blossoms, while sharp, controlled movements can suggest falling autumn leaves or a sudden gust of wind.

The fan’s colors and decorative patterns are often chosen to reflect the season, the mood of the piece, or the narrative being portrayed, allowing subtle visual cues to support the dance.

Noh Theater

In Noh, the fan (ōgi) is not merely an accessory but a strictly prescribed element of the costume.

The type of fan used — its size, color, and pattern—is determined by the role and the specific play being performed.

Different character types, such as nobles, warriors, or supernatural beings, each carry fans with established designs. Motifs such as pine trees, waves, or the moon often appear, reinforcing the symbolic world of the story.

Although the fan is used in highly stylized movements — such as slowly raising it to suggest the passage of time — its greatest significance lies in its role as a formal and essential marker of character and tradition.

Kabuki

In kabuki, the sensu or maiōgi is used with greater visual dynamism.

Through the actor’s gestures, a single fan may represent a sword, a sake cup, a letter, or another object entirely.

Bold and sweeping movements create dramatic effects, enhanced by richly decorated fan surfaces finished in gold, silver, or vivid colors.

While most performances employ a single fan, certain dances use the nimai-ōgi (two-fan) style, in which the actor holds a fan in each hand.

In Kagami-jishi (“The Mirror Lion”), for example, the performer moves both fans with controlled grace, expressing elegance and refinement through symmetry and rhythm.

Rakugo

In rakugo, Japan’s traditional comic storytelling, the fan becomes a tool of imagination rather than spectacle.

Seated alone on stage, the storyteller uses the fan to suggest a wide range of actions and objects, such as:

- Eating or drinking — as chopsticks, a sake cup, or a rice bowl

- Writing — as a brush or pen

- Everyday items — as a pipe, a sword, or a merchant’s ledger

The simplicity of the fan allows the audience to supply the missing details, making it a cornerstone of rakugo’s minimalist performance style.

Expressing Emotion and Season

Across these performing arts, the sensu conveys emotion, season, and atmosphere not only through its appearance, but through how it is opened and moved.

Even small differences in handling can change the feeling of a scene, allowing the fan to act as a quiet yet powerful visual language.

- A half-closed fan held near the face may suggest shyness or restraint

- Rapid, fluttering motions can convey excitement or tension

- A fully opened fan presented toward the audience often symbolizes welcome or celebration

Through centuries of use on stage, the sensu has become a powerful expressive medium — capable of conveying story, emotion, and atmosphere without a single spoken word.

A small break — a little side note

In Ōita Prefecture, you’ll find a charming local tradition called Tsukumi Sensu Odori, a traditional fan dance recognized as an Intangible Cultural Property of the region.

As night falls, women dressed in yukata line up under the lights, moving together in smooth, graceful rhythms. With each gentle turn of the sensu, the dance feels calm, elegant, and quietly captivating. The glow of the evening lights and the synchronized motion of the fans make the scene even more magical.

This dance is a lovely reminder that sensu are not only objects to hold, but tools that live inside local culture. In places like Tsukumi, folding fans are part of everyday tradition — bringing people together through movement, beauty, and shared memories.

Modern Uses and Global Influence

Having explored the many forms the sensu has taken over time, we now turn to its place in modern Japan.

How do people use folding fans today, and how do they balance practicality with artistry in everyday life?

Practical Use in Daily Life

During Japan’s hot and humid summers, the sensu continues to serve as a traditional and elegant way to keep cool.

Lightweight and easy to carry, it remains especially popular among adults and older generations.

Among younger generations, compact handheld electric fans are often preferred for their convenience.

However, unlike electric fans, a sensu creates a breeze quietly and without the need for batteries, making it a simple and environmentally friendly choice.

For those who value a calm presence, cultural heritage, and the gentle, graceful rhythm it brings to everyday life, the folding fan continues to be quietly cherished as part of daily life.

Interior, Souvenirs, and Fashion

Beyond their practical use, sensu are widely appreciated as decorative objects.

Fans with vibrant seasonal motifs, gold-leaf accents, or traditional wagara patterns are sold as souvenirs for travelers.

In interior design, large decorative fans (kazari-sensu) are used to bring a touch of Japanese elegance to homes and commercial spaces.

In fashion, folding fans have reappeared as accessories, carried at summer parties, weddings, and even on runways.

Global Collaborations

The sensu has also begun to attract attention as a medium of contemporary artistic expression.

Below are a few representative examples of collaborations with international artists that highlight how the folding fan is being reimagined today.

-

Sylvain Le Guen (France)

A contemporary artist who specializes in folding fans.

In 2021, he held an exhibition in Tokyo showcasing sensu as art objects, blending traditional fan structures with modern colors and compositions.

His work elevates the sensu from a functional object to a form of visual art, emphasizing its role as a cultural bridge between tradition and contemporary expression. -

Fantasista Utamaro × BANANA to YELLOW (USA / Japan)

A collaboration between a New York–based artist and a Japanese brand.

By incorporating pop-art aesthetics into the traditional form of the sensu, this project reinterprets the fan as a modern canvas—while still respecting its cultural roots.

Through such reinterpretations, the sensu continues to reveal new layers of appeal to modern audiences.

By inspiring artists around the world, this traditional craft demonstrates how heritage objects can embrace new creative voices and continue to generate timeless value.

In this way, the sensu continues to evolve in the modern world — quietly carrying its long history and traditions forward while embracing new forms of expression.

How to Choose and Care for a Sensu

After learning more about the sensu, you may be feeling inspired to own one yourself — or to give one as a thoughtful gift to someone special.

For those moments, this section offers guidance on choosing the right folding fan for different purposes, along with simple care tips to help it be enjoyed for many years to come.

Choosing the Right Sensu

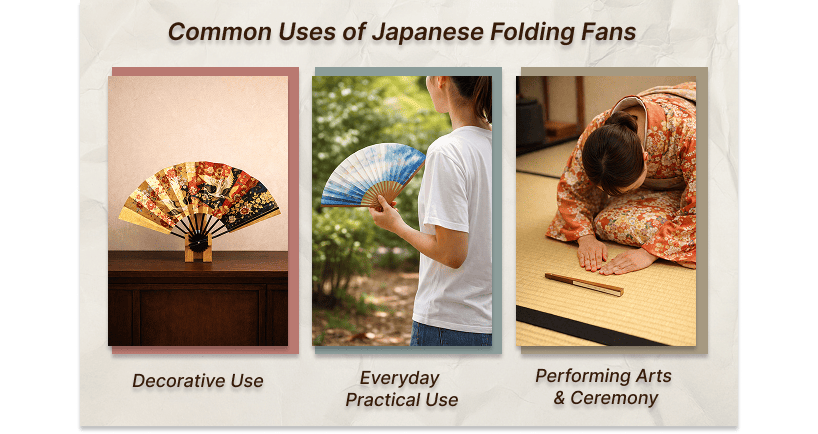

When choosing a sensu, the most important thing to consider is how you plan to use it.

Different types of folding fans are designed for different purposes, so selecting the right one will help you enjoy it more fully.

Below are some general guidelines to help you choose a sensu that suits your needs.

-

Decorative Use For interior display, a kazari-sensu is a good choice.

Look for fans with bold designs, gold or silver accents, and a solid, well-crafted structure.

Larger fans tend to create a stronger visual presence when displayed. -

Everyday Practical Use

For daily use during the summer, a lightweight natsu-ōgi is ideal.

Fans with washi paper surfaces produce a stronger breeze, while polyester surfaces are more resistant to moisture and wear.

Choose the material that best fits your lifestyle and preferences. -

Performing Arts and Ceremony

Fans used in traditional arts are designed for very specific purposes.

Maiōgi are used in Japanese dance and kabuki, while cha-sensu are used in tea ceremony.

In Noh theater, the type of fan is strictly determined by the role and the specific performance, so careful attention is required.

Where to Buy an Authentic Sensu

For readers outside Japan who are considering purchasing an authentic Japanese folding fan, there are long-established fan makers that offer international shipping.

One such example is Ibasen, a long-established traditional fan shop based in Tokyo.

For generations, Ibasen has continued to craft sensu for a wide range of purposes, including everyday use, decoration, and formal occasions such as weddings and ceremonies.

For more information, please visit their official website.

Caring for Your Sensu

Before you begin using your sensu, it is helpful to know a few simple care tips. With proper attention, a folding fan can remain beautiful and functional for many years.

-

Avoid Moisture

Rain and damp conditions can damage paper surfaces and may cause bamboo ribs to warp. -

Keep Out of Direct Sunlight

Prolonged exposure to strong sunlight can lead to fading or discoloration over time. -

Use a Protective Case

Especially for fans made with silk or gold leaf, a case helps protect against dust and scratches. -

Open and Close Gently

Forcing the fan may damage the folds or loosen the pivot. -

Store in a Cool, Dry Place

Proper storage helps prevent mold, warping, and other forms of deterioration.

With these simple precautions, a sensu can be enjoyed for a long time while retaining its beauty.

Over the years, it may even become a personal keepsake — quietly reflecting both your own taste and the enduring craftsmanship of Japan.

Take pleasure in using it, and allow it to become part of your everyday moments.

Conclusion: Unfolding Centuries of Elegance

From the imperial courts of ancient Japan to modern everyday life — and even to artistic expressions around the world—the sensu has carried far more than a simple breeze.

It is an object that has preserved and passed on stories, artistry, and tradition across centuries.

The gently expanding form of the folding fan reflects an enduring wish for prosperity, while its patterns, materials, and uses quietly express the seasons, celebrations, and spiritual values woven into Japanese culture.

Whether bringing relief from summer heat, enhancing expression on the stage, or serving as a heartfelt gift, the sensu is both a practical tool and a work of art.

To hold a sensu is to hold centuries of history in your hands.

Within each fold lives a quiet resonance of elegance, symbolism, and craftsmanship — qualities that have continued to inspire people not only in Japan, but around the world.

Why not take a sensu into your own hands, and experience Japanese culture through the gentle movement of its graceful breeze?