Kakejiku: Japan’s Living Scrolls of Art, Season, and Spirit

What if a single scroll could tell a story, capture the seasons, and bring you a moment of peace?

That is the kakejiku — a mirror of time, nature, and spirit within the Japanese home. From the fragrance of incense in temple halls to the soft light inside a tea room, kakejiku have hung on walls for centuries, changing with each season.

In winter, perhaps a snow-covered mountain; in spring, a single blooming flower.

Why does one simple scroll hold such quiet power to move us?

Whether you love art, enjoy exploring new cultures, or simply wish to slow down and breathe, come explore the world of kakejiku — where every scroll waits to unfold its own timeless story.

What Is a Kakejiku?

Before we dive into its history and meaning, let’s begin with the basics — what exactly is a kakejiku?

Understanding the Kakejiku

A kakejiku (掛け軸) is a traditional Japanese hanging scroll used to display calligraphy, paintings, or spiritual writings.

Each piece is mounted on decorative paper or silk, finished with bamboo or wooden rods — so it can be gently rolled and brought out again when the season or mood calls for it.

What Makes a Kakejiku Special

The most distinctive feature of a kakejiku is that it isn’t meant to hang in the same place all the time, like a framed painting or artwork on a wall.

A kakejiku changes with the rhythm of everyday life — replaced to reflect the season, a special occasion, or the theme of a tea ceremony.

This custom reflects a uniquely Japanese concept called shitsurai (室礼) — the art of preparing a space in harmony with time, place, and purpose.

Where You’ll Find a Kakejiku

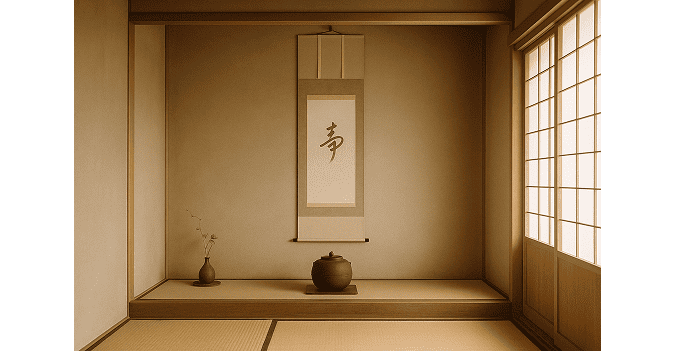

Do you know where a kakejiku is usually displayed?

Traditionally, it hangs in a small recessed alcove called a tokonoma (床の間) — a feature found in Japanese-style rooms.

In this quiet space, the scroll becomes the spiritual center of the room: calm, elegant, and deeply expressive.

The kakejiku sets the mood for the entire room, inviting reflection, stillness, and a sense of beauty that fills the air.

In this way, a kakejiku is like a seasonal whisper upon the wall — soft, graceful, and filled with quiet meaning.

Each scroll carries its own gentle presence, expressing not only art but the flow of nature, the feelings of the heart, and the warm spirit of Japanese hospitality (omotenashi).

A Brief History of Kakejiku

Now that we’ve learned the basics of the kakejiku, let’s take a closer look at its history — how this simple scroll evolved into a cherished part of Japanese life and aesthetics.

From Sacred Images to Samurai Elegance

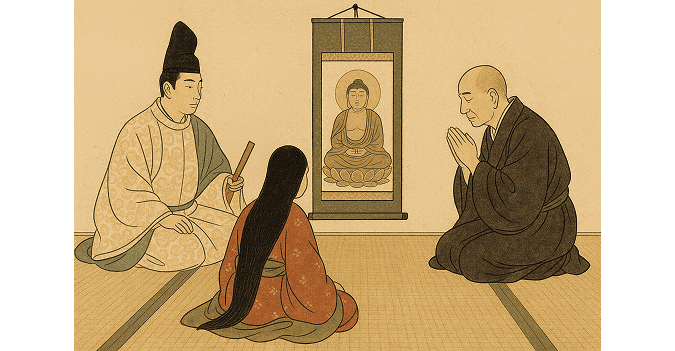

The story of the kakejiku begins more than a thousand years ago, during the Asuka period (6th–7th century).

It was first brought from China as a way to display Buddhist images (仏画) and scriptures.

By the Heian period (794–1185), these scrolls adorned the homes of aristocrats and monks, serving as objects of worship.

At this time, they were rare treasures — almost never found in ordinary households.

Later, in the Kamakura period (12th–14th century), the rise of Zen Buddhism and ink wash painting (sumi-e) transformed the kakejiku from purely religious art into a form of spiritual expression through simplicity.

Entering the World of Tea

During the Muromachi period (14th–16th century), a new style of Japanese architecture, shoin-zukuri, introduced the tokonoma — the alcove we know today.

This became the perfect place to display a kakejiku, especially during the tea ceremony (chanoyu).

Under the influence of Sen no Rikyū, the great tea master, the scroll took on a new role: to express seasonality, harmony, and the quiet hospitality at the heart of Japanese culture.

In the tea room, a single scroll could speak volumes — setting the tone for the entire gathering.

The Scrolls of Society

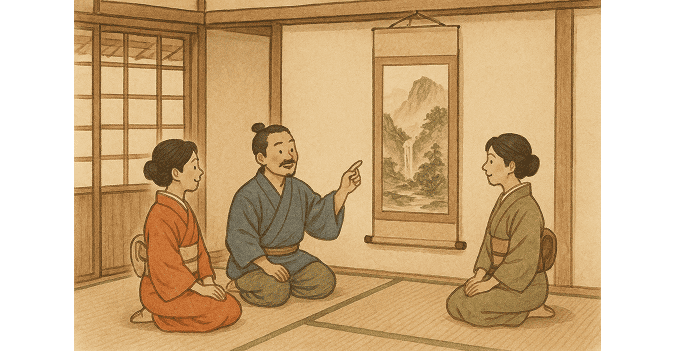

By the Azuchi-Momoyama period (late 16th century), kakejiku were no longer limited to temples and noble estates.

In samurai reception rooms, hosts carefully chose the scroll to match the status of the guest, the time of day, or the season — sometimes changing it several times a day.

This thoughtful attention reflected refinement, courtesy, and aesthetic awareness.

In the Edo period (17th–19th century), the scroll truly entered daily life.

Townspeople and cultural elites alike began to enjoy them.

As bunjin-ga — a style of literati painting — became popular, calligraphy and art came together as a personal expression of thought and feeling.

Some even mounted their own creations as kakejiku, turning the scroll into a canvas for the self.

With the spread of ukiyo-e and woodblock printing, affordable scrolls became widely available, bringing art into the homes of ordinary people.

Modern Shifts and a Gentle Revival

In the Meiji and Taishō periods (late 19th to early 20th century), the rise of Japanese-style painting (nihonga) and encounters with Western art gave new life to the kakejiku.

It became part of Japan’s artistic renaissance and began attracting attention abroad.

After World War II, however, Western-style homes became common, and tokonoma alcoves gradually disappeared.

Daily use of kakejiku declined — yet their value grew.

What once adorned everyday homes became museum pieces and cultural treasures, admired for their quiet beauty and depth of spirit.

Today, you can still find them in temples, tea rooms, and exhibitions, where each scroll continues to reflect Japan’s enduring sense of elegance, harmony, and mindfulness.

Styles and Themes of Kakejiku

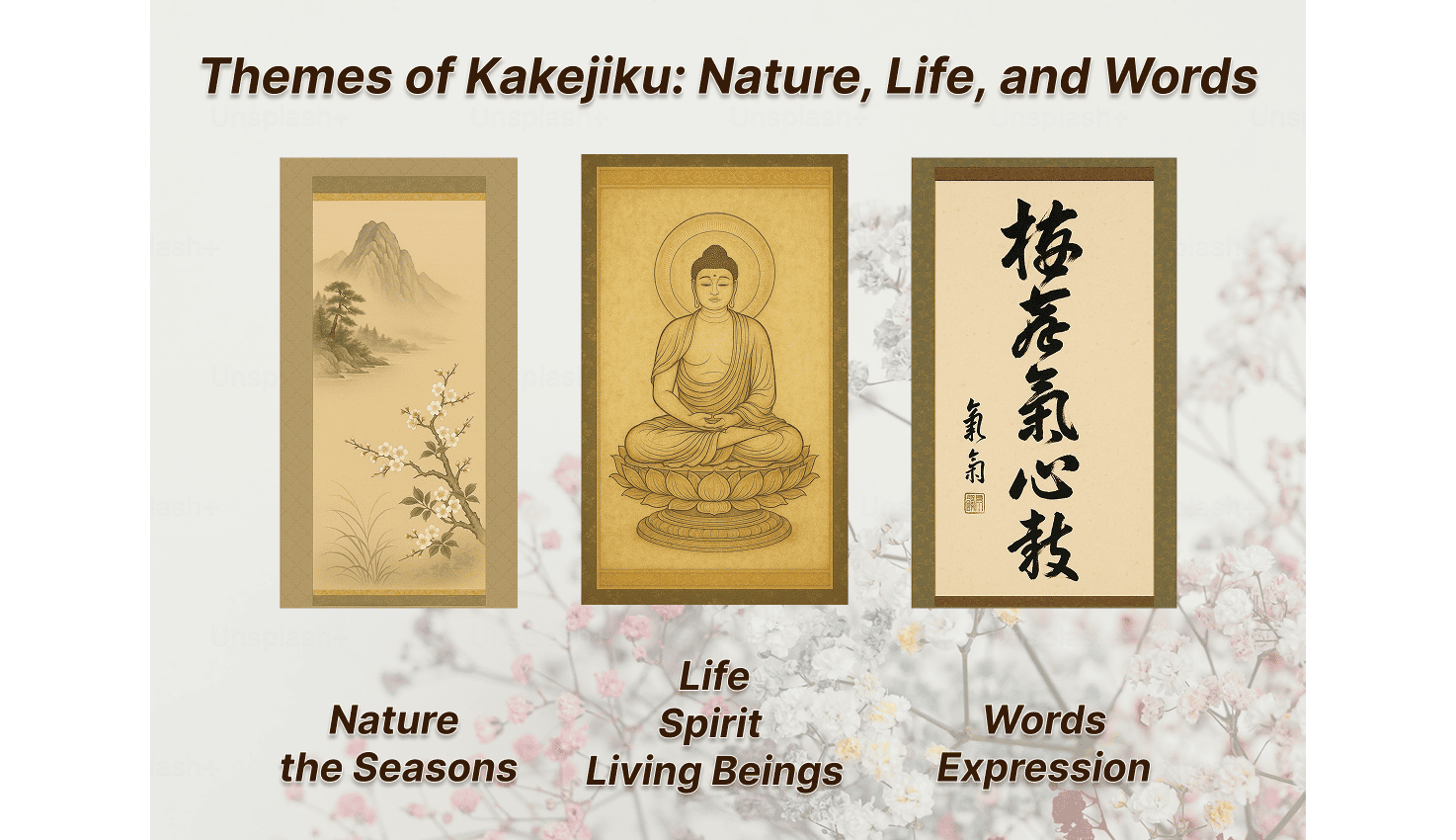

What kinds of scenes or subjects are found on a kakejiku?

Each scroll tells a story — sometimes through nature, sometimes through people or words — but always with beauty and meaning.

Here’s how the themes of kakejiku can be broadly grouped.

1. Nature and the Seasons

Many scrolls capture the ever-changing beauty of Japan’s natural world — its landscapes, plants, and gentle transitions through the four seasons.

These artworks invite calm reflection and a sense of connection with nature.

-

Landscape Painting (山水画, Sansuiga)

Depictions of mountains, rivers, and valleys, showing the serenity of nature in each season.

Cherry blossoms in spring, red leaves in autumn, or snow in winter all express nature’s quiet rhythm. -

Bird-and-Flower Painting (花鳥画, Kachōga)

Elegant scenes of birds and flowers, symbolizing harmony between all living things.

A crane beside plum blossoms or sparrows on bamboo represent the beauty of balance in nature. -

Scenic Views (風景画, Fūkeiga)

Paintings of villages, forests, and traditional homes, sometimes including people.

These evoke nostalgia and peace — a moment of rest found in daily life.

2. Life, Spirit, and Living Beings

Some scrolls focus on beings — divine, human, or animal — each carrying symbolic meaning or spiritual depth.

-

Buddhist and Shinto Imagery (仏画・神画, Butsuga / Shinga)

Scrolls depicting Buddhas, deities, or sacred mandalas, representing faith, protection, and gratitude.

They connect daily life with the spiritual world. -

Animal Painting (動物画, Dōbutsuga)

Artworks featuring both real and mythical creatures — tigers, cranes, dragons, and kirin.

Each animal symbolizes something: the tiger for strength, the crane for longevity, and the dragon for wisdom and power. -

Portraits and Figures (人物画, Jinbutsuga)

Scrolls of heroes, monks, or legendary figures that express wisdom, virtue, and the human spirit.

3. Words and Expression

Among all types, calligraphy stands apart.

It doesn’t depict objects or people — instead, it captures the artist’s heart and state of mind through the movement of the brush.

- Calligraphy (書, Sho)

Written Zen phrases, poems, or single words that embody simplicity and mindfulness.

The power lies not in the meaning of the word alone, but in the energy of the brushstrokes themselves.

In this way, kakejiku express the full range of Japanese thought — from the quiet beauty of nature, to the depth of spirit, to the poetry of words.

Choosing a scroll to match the season, a celebration, or simply one’s mood turns a room into a reflection of the heart.

Anatomy of a Kakejiku

A kakejiku reflects the mood of a space and even the heart of the person who hangs it.

But have you ever wondered how one is put together?

In fact, a kakejiku is carefully built from many different parts — each one working together to shape its beauty and meaning.

Let’s take a closer look at what these parts do and how they fit together.

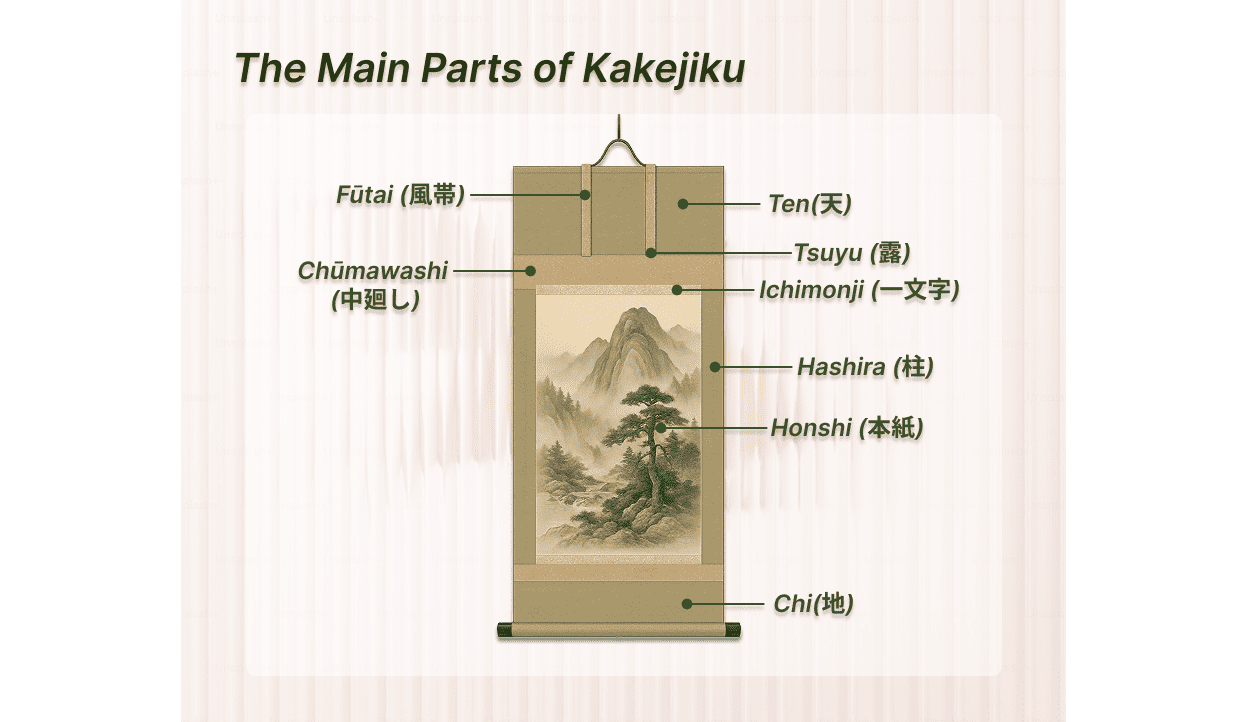

Main Parts

Let’s first explore the key components that form the main body of a kakejiku, each with its own role in both design and symbolism.

-

Honshi (本紙)

The main artwork at the center of the scroll — usually a painting or calligraphy.

This is the part that people focus on.- If made of paper: shihon (紙本)

- If made of silk: kenpon (絹本)

-

Ichimonji (一文字)

Two thin horizontal strips of fabric — one above and one below the main artwork.

They act like picture frames, helping the eye focus on the artwork and adding a touch of decoration. -

Chūmawashi (中廻し)

The broad fabric that surrounds the artwork.

It connects the artwork in the center to the outer edges, balancing color and texture. -

Tenchi (天地)

Literally “heaven and earth.” These are the top (ten) and bottom (chi) sections of fabric.

They define which way is up and which is down on the scroll — the ten gives space and openness above the artwork, while the chi gives weight and stability below. -

Hashira (柱)

The two vertical side borders on the left and right.

They complete the frame of the scroll and keep the overall shape balanced. -

Fūtai (風帯)

Two long hanging strips that come down from the top of the scroll.

They don’t serve a practical purpose — they’re purely decorative, giving the scroll a more formal and elegant look. -

Tsuyu (露)

Small decorative ends attached to the fūtai.

The word tsuyu means “dew,” a poetic name that suggests lightness and delicacy.

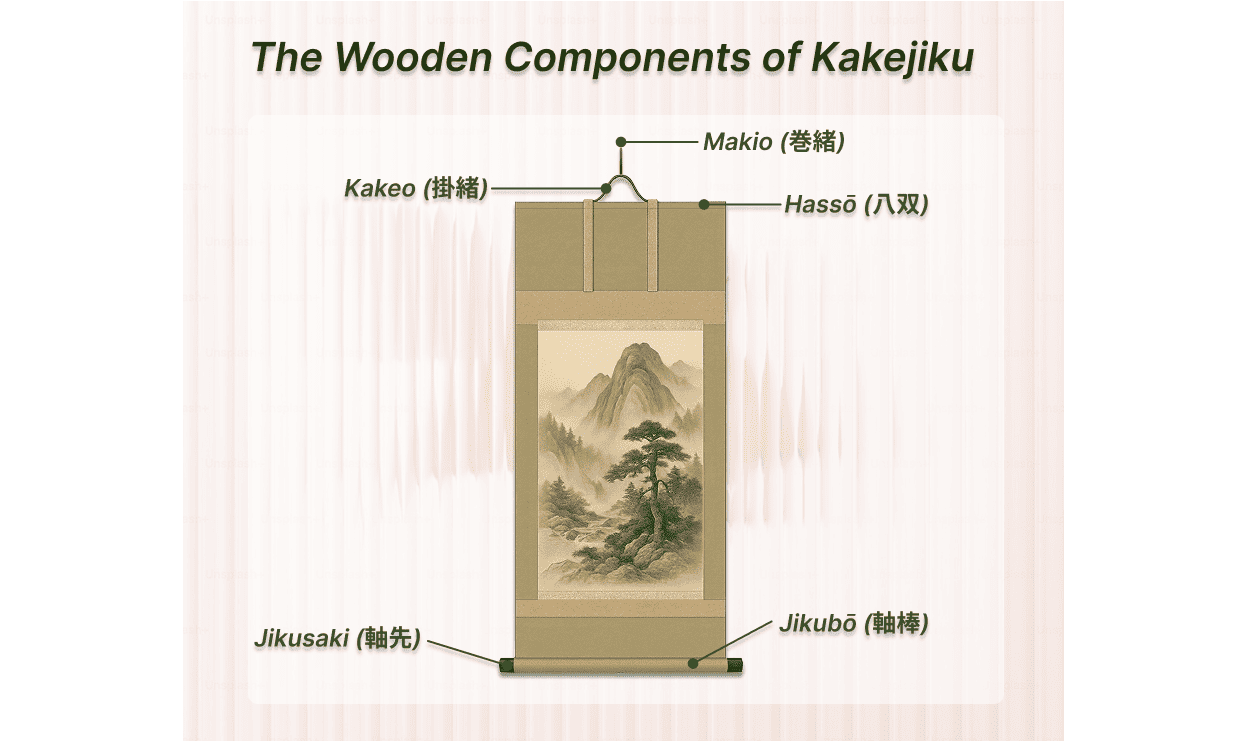

Wooden Components

Next, let’s look at the wooden parts that support the scroll — the pieces that hold everything together and allow the kakejiku to hang and roll smoothly.

-

Hassō (八双)

The round wooden bar at the top of the scroll.

It supports the scroll and helps it hang straight. -

Jikubō (軸棒)

The wooden rod at the bottom, hidden inside the base of the scroll.

It allows the scroll to be rolled up smoothly when you store it. -

Jikusaki (軸先)

The knobs at both ends of the bottom rod.

You hold these when rolling or unrolling the scroll — they also add a small decorative touch, often made of wood or ceramic. -

Kakeo (掛緒)

The cord used to hang the scroll on a hook or nail.

It’s the part that holds the entire piece up on the wall. -

Makio (巻緒)

A separate string used to tie the scroll when it’s rolled up.

It keeps the scroll safe and neat when stored away for the next season.

How does it look to you?

Even though a kakejiku may seem like a simple hanging scroll, you can see that it’s actually made up of many delicate parts working together in harmony.

A small break — a little side note

Would you like to see how a kakejiku — made up of many intricate parts — is brought to life?

This video takes you inside the workshop of traditional Japanese scroll makers, where you can witness the delicate process, the handcrafted techniques, and the sincere passion poured into every single piece.

Every brushstroke, every layer of fabric, and every movement of the craftsman reflects centuries of tradition and quiet dedication.

Watch how patience and devotion transform simple materials

into timeless works of art.

Two Philosophies of Mounting: Yamato and Bunjin

Did you know that kakejiku are not only about the artwork itself, but also about the art of mounting, known as hyōsō (表装) — the traditional craft of turning calligraphy or paintings into hanging scrolls?

The choice of fabric, decorative borders, and overall balance is more than design — it defines the scroll’s formality and reflects a philosophy of beauty, spirit, and the way art is experienced.

Two main styles of mounting have taken shape in Japan, each expressing a distinct way of thinking about life and art.

Let’s take a closer look at these two traditions.

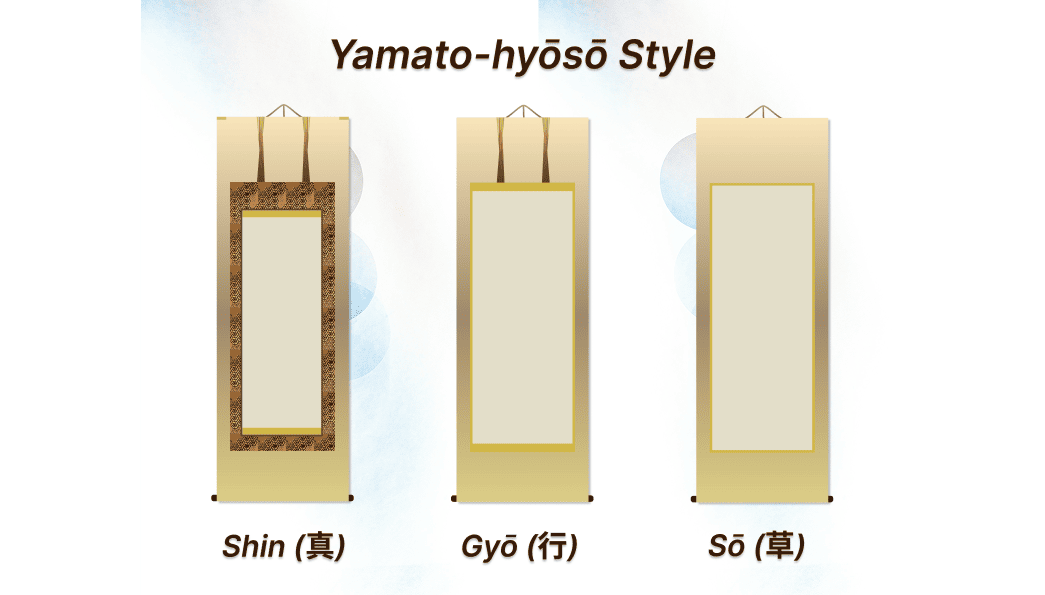

Yamato-hyōsō — Harmony, Ceremony, and Order

In Yamato-hyōsō, scrolls are divided into three levels of formality — each one defining when a scroll is used and how it should look and feel.

-

Shin (真) — Formal and dignified

Used for Buddhist paintings, mandalas, and sacred calligraphy.

The wide, symmetrical borders give a solemn and balanced impression. -

Gyō (行) — Balanced and graceful

Commonly chosen for seasonal themes, Chinese paintings, or classical Japanese art.

The side borders are simplified, creating a calm and flexible appearance. -

Sō (草) — Light and expressive

Favored for Zen calligraphy, poetic ink works, and tea room displays.

The design feels airy and spontaneous, with narrower borders and a relaxed rhythm.

Together, these three forms show how Yamato-hyōsō reflects not just technique, but a mindset — moving from the formal and sacred to the simple and sincere.

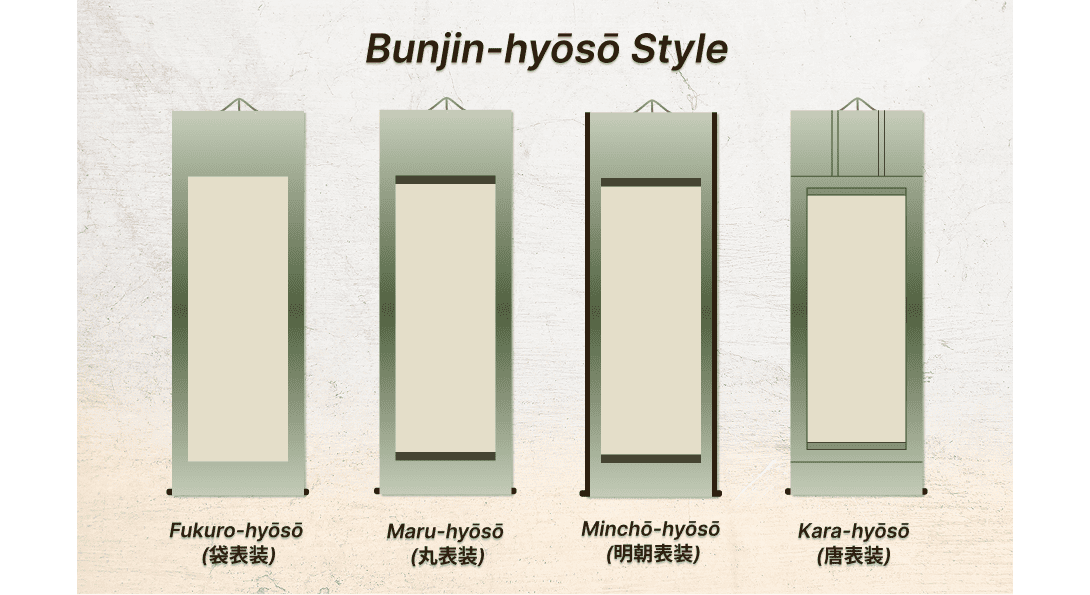

Bunjin-hyōsō — Simplicity, Expression, and the Literati Spirit

The bunjin-hyōsō style carries a completely different spirit.

Born from Chinese literati culture, it was shaped by scholars and poets who painted not to impress others, but to express their thoughts and emotions.

This idea took root in Japan during the Edo period, where simplicity and individuality became a new kind of elegance.

Unlike the precise order of Yamato mountings, bunjin-hyōsō values natural flow, freedom, and personal taste.

- Fukuro-hyōsō (袋表装) – The simplest form, with only the artwork and one type of fabric. When decorative borders (ichimonji) are added, it’s called maru-hyōsō (丸表装).

- Maru-hyōsō (丸表装) – A soft, rounded appearance with the same fabric all around, and a thin decorative line above and below the artwork. Fūtai (wind strips) are often omitted for simplicity.

- Minchō-hyōsō (明朝表装) – Adds vertical side borders (minchō), creating a more refined look. This was especially popular among Edo-period artists.

- Kara-hyōsō (唐表装) – A version that includes thin gold-thread lines (sujimawashi) between the fabric sections, offering a delicate and elegant finish.

Where Yamato-hyōsō follows formality and balance, Bunjin-hyōsō celebrates freedom, personality, and a quiet conversation between art and nature.

In their own ways, both styles reveal what makes Japanese aesthetics unique — the timeless search for harmony between discipline and freedom, form and feeling, and outer beauty and inner spirit.

Where to Buy a Kakejiku: A Guide for International Collectors

Up to this point, we’ve explored kakejiku from many angles — their history, styles, and the craftsmanship behind their creation.

Perhaps now, you’re wondering what it’s like to see one in person — or even to bring one into your own home.

If you live outside Japan, finding authentic and trustworthy pieces can be challenging, since many shops and auction sites operate only in Japanese or don’t offer international shipping.

That’s why in this section, we’ll introduce some reliable sources and practical tips — whether you’re looking to purchase a scroll from abroad or hoping to find one during your visit to Japan.

Buying from Outside Japan

1. Nomura Kakejiku (野村掛軸)

A rare Japan-based shop that offers English-language support and worldwide shipping.

They carry a wide range of scrolls — from Zen calligraphy and seasonal landscapes to custom framing and mounting services.

Visit Art Nomura (official site)

A small break — a little side note

Surprisingly, it was someone living all the way in Singapore!

In this short video, you’ll see how ART NOMURA helped an overseas customer choose a real Japanese hanging scroll.

Watch how a piece of art with centuries of history finds a new home across the sea.

2. Etsy or eBay (selected sellers)

Some independent sellers on global marketplaces like Etsy and eBay specialize in vintage Japanese art, including hanging scrolls.

However, because these are often one-of-a-kind antiques, quality and authenticity can vary.

Here are a few points to keep in mind:

- Check the condition carefully — scrolls may show age or wear

- Confirm international shipping availability and costs

- Review the seller’s ratings and return policies

- Look for details on provenance or artist information

Visit Etsy (official site)

Visit eBay (official site)

Buying Kakejiku in Japan (When You Visit)

If you have the chance to visit Japan, exploring in person opens up many more possibilities.

You can see the materials, textures, and craftsmanship firsthand — and sometimes even speak with the artisans or curators themselves.

1. Department Store Art Salons

Prestigious department stores such as Mitsukoshi (Nihombashi) and Isetan (Shinjuku) regularly hold art exhibitions and fairs featuring kakejiku alongside ceramics, lacquerware, and other traditional crafts.

- Example: Isetan’s “The Stories” Exhibition (2023) featured modern calligraphy scrolls in contemporary interior spaces.

- Example: Mitsukoshi Nihombashi Art Fair (2022) showcased works by both classical and modern scroll artists.

2. Traditional Art Galleries and Specialty Shops

Historic cities like Kyoto, Kanazawa, and Tokyo’s Nihombashi district are home to long-established art galleries specializing in antique scrolls, mounting restoration, and custom commissions.

If you’re visiting temples or art streets, ask the staff for recommendations — many galleries curate their displays according to the season or festival calendar.

Final Thoughts

Finding an authentic kakejiku abroad may take patience, but it’s worth the effort.

From trusted shops like Nomura Kakejiku to art salons in Japan’s major cities, each scroll carries not only artistic value but also a quiet spirit — one that connects space, season, and heart.

Choose the one that speaks to you, and you’ll bring home more than an artwork — you’ll bring home a piece of Japanese culture itself.

Conclusion: A Living Scroll of Time and Spirit

A kakejiku is more than decoration on a wall — it is a quiet companion that reflects the passing seasons and the rhythm of daily life in Japan.

Each scroll holds within it a sense of seasonal awareness, refined beauty, and the warm spirit of omotenashi — the wish to welcome others with grace and sincerity.

From ancient temples to modern homes, from Zen calligraphy to contemporary art, kakejiku continue to bridge tradition and innovation, whispering stories of nature, culture, and time to those who take a moment to pause and see.

Whether you hang one in a tea room, a study, or a quiet corner of your home, a kakejiku invites you to slow down, reflect, and simply be present.

Let the scroll speak — softly, seasonally, and from the heart.