Ikebana: The Art of Nature, Silence, and Subtle Grace

What if arranging a single flower could bring you peace?

In Japan, through the tradition of ikebana, everyday flowers are transformed into quiet expressions of harmony and stillness.

It’s not just decoration—it’s a form of meditation, a dialogue between you and nature.

Have you ever wondered why people find such beauty in the simplicity of ikebana?

Let’s uncover that mystery together.

Join us on a journey to discover how this timeless Japanese art began and how it has continued to evolve through the centuries.

What Is Ikebana?

Ikebana is the Japanese art of flower arrangement.

But it’s not just about putting flowers in a vase or making something look beautiful.

It’s a way of expressing life through nature—a quiet art that reflects the changing seasons through flowers, branches, and leaves.

Imagine a single branch leaning gently to one side, with a delicate blossom opening beside it.

In that calm space, ikebana creates a sense of balance and serenity, filling the room with subtle grace.

This is the true essence of ikebana: balance, simplicity, and mindfulness.

Every element—each stem, angle, and open space—holds meaning. Even the surrounding air becomes part of the expression.

A small break — a little side note

Ever wondered what ikebana really looks like beyond words?

Here’s a short video that shows real ikebana pieces—each simple, delicate, and quietly mesmerizing.

Sit back, relax, and let the beauty of these living arrangements draw you in.

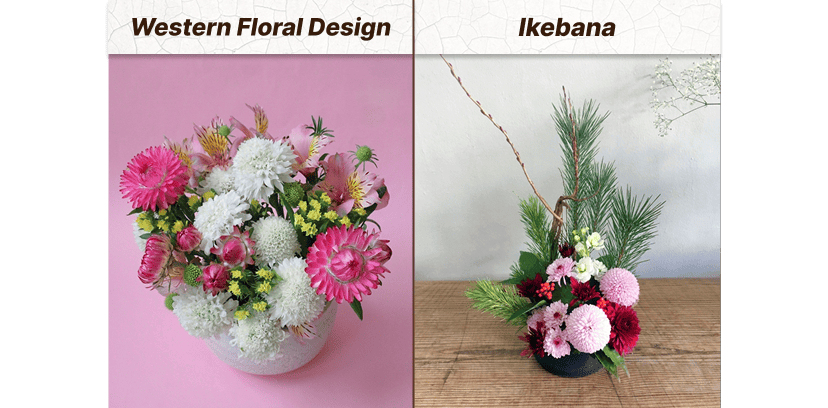

How Ikebana Differs from Western Floral Design

Let’s take a look at how Japanese ikebana differs from Western floral design.

Both share the same goal—to make flowers look beautiful—but the way they express that beauty is quite different.

Here’s a simple comparison to help you see the contrast:

| Western Floral Design | Ikebana |

|---|---|

| Focuses on fullness and symmetry | Emphasizes balance and asymmetry |

| Designed to look attractive from all angles | Created with a clear front view like a painting |

| Uses many flowers to fill the space | Values empty space (ma) as part of the design |

| Highlights blooms as the main beauty | Highlights lines, branches, and stems |

| Aims for color harmony and abundance | Seeks seasonal meaning and emotional simplicity |

It’s fascinating how two art forms, both devoted to flowers, can take such opposite approaches to expressing beauty.

Roots of Reverence: Ikebana’s Sacred Beginnings

So how did this uniquely Japanese art of ikebana begin?

Long before it was recognized as an art form, the act of arranging plants carried a spiritual meaning deeply connected to Japan’s view of nature.

Let’s travel back in time to explore the origins of ikebana.

Ancient Beliefs: Nature as Sacred

In ancient Japan, people believed that spirits called kami lived in trees, rocks, and rivers.

Placing plants upright was seen as a way to invite these divine presences into a space.

Even when cut, plants were thought to hold living energy, inspiring awe and respect for nature’s invisible life.

Buddhism and Early Offerings

When Buddhism arrived in the 6th century, flowers began to be offered at temple altars.

These offerings, called kuge, were meant to honor the Buddha—but over time, they also became symbols of harmony and devotion.

By the Heian period (794–1185), nobles were placing small vases of seasonal flowers in their homes, admiring their beauty and writing poems about them.

The Birth of an Art Form

During the Muromachi period (1336–1573), temple priests in Kyoto, especially Senkei of the Ikenobō family, refined these arrangements into formal designs.

This became known as rikka—“standing flowers”—a grand style meant to represent mountains, rivers, and clouds in miniature.

Ikebana was no longer just ritual; it was art.

From Temples to Everyday Life

By the Edo period (1603–1868), ikebana spread beyond temples and aristocrats.

Simpler styles like shōka made it possible for townspeople to enjoy flower arranging in their homes.

What began as a sacred offering had now blossomed into a cultural tradition shared by everyone.

A Meeting of East and West

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as Japan opened to the world, Western artists and architects discovered ikebana’s quiet beauty.

Around the same time, Japanese masters began creating modern styles such as moribana and jiyūka that embraced freedom and creativity.

From sacred roots to contemporary art, ikebana has continued to evolve—always balancing tradition and change.

From sacred rituals to an art of gentle reflection, ikebana has always helped people reconnect with nature and rediscover inner balance.

Types and Styles of Ikebana

The styles that appeared throughout ikebana’s long history remain among the most well-known today.

Let’s take a closer look at each style and the unique sense of beauty it expresses.

Rikka (立花) – Standing Flowers

Born in the Muromachi period (1336–1573), rikka is the oldest and most formal style of ikebana.

It was created to represent the grandeur of nature—mountains, rivers, and clouds—within a single vase.

With tall, upright branches and rich layers, it feels like a miniature landscape that captures the power and harmony of the natural world.

Nageire / Heika (投げ入れ・瓶花) – Spontaneous or Vase Flowers

Nageire means “thrown-in,” but it’s anything but careless.

This style is natural and spontaneous, as if the flowers simply found their own place.

Closely linked to the tea ceremony, it embodies the calm beauty of wabi-sabi—elegant simplicity and imperfection.

Seika / Shōka (生花・正花) – Pure or Orthodox Flowers

Seika (or shōka) follows a three-line structure that represents Heaven (shin), Human (soe), and Earth (hikae).

It may look simple, but the balance between these three lines creates a feeling of perfect harmony.

This style reminds us that beauty often comes from clarity and restraint, not abundance.

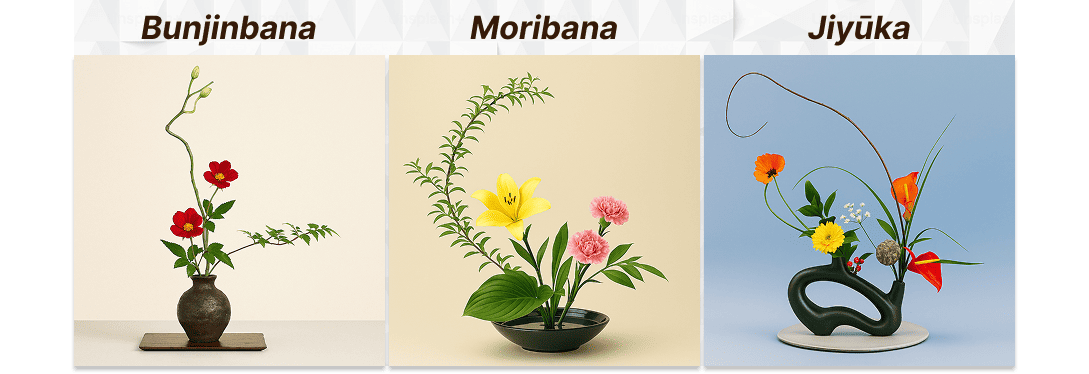

Bunjinbana (文人花) – Literati Flowers

Inspired by Chinese literati art, this style feels poetic and contemplative.

It focuses on the relationship between flower, vase, and empty space, often resembling an ink painting or a short poem.

Each arrangement feels like a quiet thought expressed in flowers.

Moribana (盛花) – Piled-Up Flowers

Introduced in the modern era, moribana uses a shallow dish called suiban and a kenzan (needle holder) to fix flowers in place.

It allows for horizontal movement and open space, giving a more natural and three-dimensional look.

Bright colors and wide compositions make this style perfect for modern homes and exhibitions.

Jiyūka (自由花) – Free-Style Ikebana

Jiyūka means “free flowers,” and it’s exactly that—freedom without rules.

Artists combine natural and man-made materials like wood, metal, paper, or glass to explore new ideas.

This contemporary style turns ikebana into modern art, full of personal expression and creativity.

Each of these styles reveals a different side of ikebana’s heart—from traditional elegance to modern imagination.

Yet in every style, the spirit stays the same—to capture the beauty of flowers and tell a quiet story, as if speaking gently with nature itself.

Ikebana Schools: Tradition and Transformation

In addition to the various styles that developed throughout history, ikebana also has different schools, or ryūha.

Each school carries its own unique philosophy and continues to evolve the art by blending these ideas with traditional styles.

Among them, three major schools stand out: Ikenobō, Ohara, and Sōgetsu.

Let’s take a closer look at what makes each one special.

Ikenobō School (池坊)

The Ikenobō School, founded in Kyoto during the 15th century, is considered the origin of ikebana.

It began with priests at Rokkakudō Temple, who arranged flowers as offerings and later refined them into elegant art forms.

Key Features:

- Oldest and most traditional school of ikebana

- Originated from temple flower offerings

- Developed classic styles such as rikka and shōka

- Emphasizes grace, structure, and spiritual balance

- Still the largest and most influential school today, leading the world of ikebana

Ohara School (小原流)

Founded in the late 19th century (Meiji era, 1868–1912) by Unshin Ohara, this school brought innovation to the world of ikebana.

It introduced the moribana style, which uses shallow containers (suiban) and pin holders (kenzan) to create open, natural landscapes.

Key Features:

- Creator of the moribana style

- Uses wide, shallow containers for horizontal compositions

- Blends Western flowers with Japanese aesthetics

- Focuses on seasonal beauty and natural rhythm

- Perfect for expressing landscapes and scenes from nature

Sōgetsu School (草月流)

Founded in the 20th century by Sōfū Teshigahara, the Sōgetsu School revolutionized ikebana with a modern, artistic spirit.

At the heart of the Sōgetsu School is the belief—introduced by its founder Sōfū Teshigahara—that “Ikebana can be created anytime, anywhere, by anyone.”

Key Features:

- Most modern and avant-garde of the major schools

- Encourages freedom, creativity, and self-expression

- Incorporates materials like metal, glass, wood, and paper

- Bridges traditional Japanese beauty and contemporary art

- Known worldwide for bold, sculptural designs

Together, these three schools show how ikebana has grown from sacred temple offerings into a living art that embraces both tradition and transformation. Each continues to nurture the spirit of ikebana—quiet, balanced, and ever-evolving.

The Philosophy and Aesthetics of Ikebana

Ikebana is not just about visual beauty.

Behind each arrangement lies a quiet philosophy that teaches us to slow down, observe with care, and discover the deeper beauty of the world through simplicity.

Now, let’s take a closer look at the philosophy behind ikebana and how it helps us find beauty in every moment.

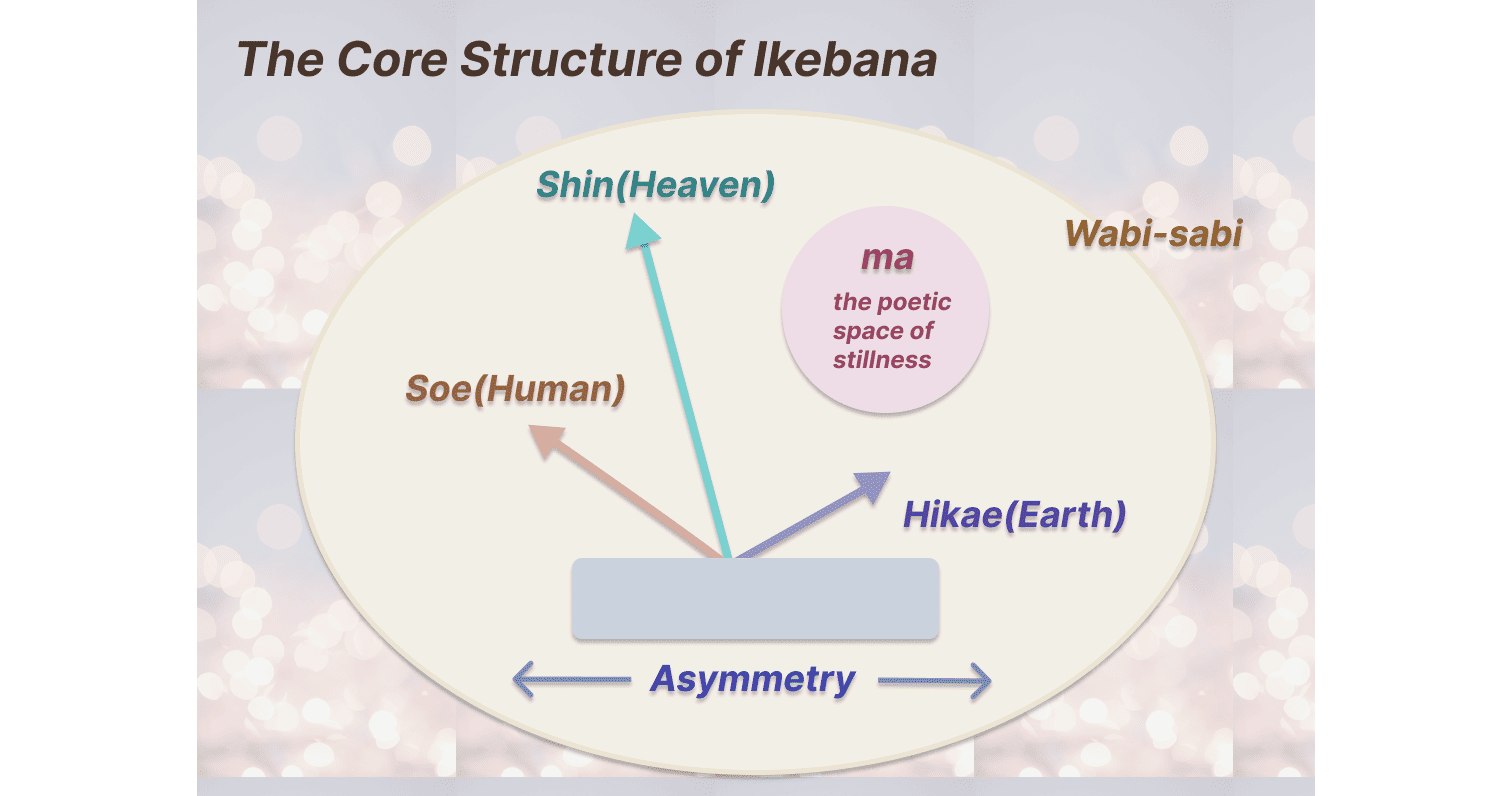

Core Aesthetic Principles

What are the aesthetic principles that shape ikebana’s quiet sense of elegance?

Let’s explore the timeless Japanese philosophies that continue to inspire this art.

- Shin, Soe, Hikae (Heaven, Human, Earth) –

Every arrangement is built upon three main lines, representing the balance between the spiritual, human, and natural worlds. - Asymmetry (非対称) –

Instead of seeking perfect symmetry, ikebana values natural imbalance and movement—like the flow of a branch or the bend of grass in the wind. - Ma (間) –

The empty space around the flowers is not “nothing.” It is the breath of the arrangement, a pause that creates rhythm and meaning. - Wabi-sabi (侘び寂び) –

A sense of quiet beauty found in imperfection and impermanence—aged wood, fading petals, or the gentle curve of a simple stem.

When these ideas come together, they create a harmony that feels both alive and serene. In ikebana, even the air around the arrangement and the passing moments become part of its beauty.

The Sensitivity of the Seasons

A true ikebana arrangement is always in tune with the changing seasons.

Every choice of material reflects a particular moment in nature’s cycle.

To show how the seasons influence ikebana, here is a simple table that introduces their expressions and meanings.

| Season | Symbolism & Materials | Feeling or Message |

|---|---|---|

| Spring | Young branches and early blossoms | Awakening, hope, and new beginnings |

| Summer | Lush greens and open flowers | Energy, vitality, and the fullness of life |

| Autumn | Red and golden leaves, late blooms | Maturity, reflection, and quiet beauty |

| Winter | Evergreens and bare branches | Stillness, endurance, and inner strength |

By selecting materials that match the season, ikebana becomes a poem written in nature’s language.

Even a single branch or flower can express the passage of time—the joy of blooming, the sadness of fading, and the peace of letting go.

The Spirit of Mindfulness

In ikebana, the process is just as important as the finished work.

Each cut, each placement, and each pause is done with quiet focus, drawing you inward as you arrange. It becomes a meditative practice—an inner dialogue between yourself and nature.

The time spent arranging flowers is also a time to slow down, breathe, and reconnect with your own heart.

Through ikebana, we learn to reflect, to grow, and to rediscover our gentle strength—and the subtle grace—within ourselves.

Ikebana in Daily Life: Bringing Nature into Everyday Spaces

Ikebana has a long history and tradition—but how has it found its place in everyday life?

Let’s take a closer look at how ikebana lives on in our daily lives.

Ikebana in the Home

For centuries, ikebana has been displayed in the tokonoma—a small alcove in traditional Japanese homes used to welcome guests and reflect the changing seasons.

Placing flowers in this space was more than decoration; it was an expression of the host’s thoughtfulness, respect, and gratitude toward nature.

Even today, some homes in Japan still keep this tradition alive.

In modern houses, where the tokonoma may no longer exist, arrangements are often placed in entrance halls, living rooms, or other spaces where they can be easily seen.

Beyond their aesthetic appeal, these arrangements bring a sense of calm and harmony, gently inviting nature’s quiet presence into the home.

In a fast-moving world, ikebana invites us to pause—to create a quiet corner where calm and grace can quietly unfold.

Ikebana in Modern Spaces

Beyond private homes, ikebana also plays an important role in many public spaces.

Here are some of the places where you can encounter its quiet beauty:

- Hotels and restaurants – Seasonal arrangements create an atmosphere of elegance and hospitality.

- Corporate offices – Bring a sense of calm and balance, offering a gentle pause amid the rush of daily work.

- Hospitals and clinics – Add warmth and healing energy through the beauty of nature.

- Art galleries and museums – Present ikebana as contemporary art, reimagining traditional forms in creative new ways.

In each of these places, ikebana transforms the atmosphere in its own way. Wherever it appears, it draws the eye and softens the space—offering a moment of beauty, peace, and quiet reflection.

Through its presence, even ordinary places can feel special, reminding us that harmony and stillness can exist anywhere.

Ikebana Around the World: A Living Tradition Across Cultures

Did you know that ikebana is no longer limited to Japan?

Today, this traditional art is known and loved around the world—practiced in more than 40 countries through Ikebana International and countless local chapters.

In this section, let’s explore how ikebana continues to flourish globally—from large international exhibitions to local community workshops that share its quiet beauty across cultures.

Global Exhibitions and Cultural Exchange

Not only in Japan—ikebana artists also gather in the United States for major exhibitions.

Notable recent exhibitions:

-

Kyoto, Japan – Ikebana International World Convention (April 2025)

The latest edition gathered creators from around the world under the theme “Succeed and Continue,” celebrating how the art evolves while honoring its roots. -

Tacoma, Washington (U.S.) – “Glass in Bloom: An Ikebana Exhibition” (March–April 2025)

The Museum of Glass showcased floral works alongside luminous glass sculptures. -

Portland, Oregon (U.S.) – Ikebana International Chrysanthemum Show

Held annually at the Portland Japanese Garden, where local artists express seasonal beauty in a peaceful setting.

These exhibitions show how ikebana continues to inspire dialogue between nature, art, and culture around the world.

Note: Dates and details are subject to change. Information based on official announcements as of 2025.

Learning and Sharing the Art

Ikebana’s unique philosophy is also spreading through education and community exchange.

Where learning meets tradition:

- Japan House, University of Illinois (U.S.) – Offers classes in ikebana, tea ceremony, and calligraphy, helping students and locals discover the essence of Japanese aesthetics.

- Maison de la Culture du Japon à Paris (France) – Regular workshops bring the art of ikebana to new European audiences.

- Local chapters of Ikebana International – Host free public exhibitions and demonstrations, allowing anyone to experience the meditative calm of flower arranging.

Through these programs, ikebana becomes a bridge—connecting cultures, generations, and hearts.

Art Meets Diplomacy and Design

Ikebana also finds its place in diplomacy, architecture, and modern art.

Recent highlights:

- Brussels, Belgium – The Belgium Chapter of Ikebana International presented a special exhibition at the Japan Mission to the European Union, marking 50 years of Japan–EU friendship and celebrating Expo 2025 Osaka.

- Rome, Italy – The MAXXI Museum hosted “The Path of Flowers: Ikebana Ikenobō” and “Ikebana Sōgetsu”, blending ikebana with contemporary architecture and art.

Masters from both schools demonstrated how tradition and innovation can bloom together in perfect harmony.

Through exhibitions, workshops, and cultural collaborations, ikebana serves as a bridge connecting people and nations across the world.

Its unique blend of beauty, meditative philosophy, and harmony with nature has become a universal language—communicating quietly through the art of flowers.

How to Experience Ikebana: Tools, Practice, and Learning

Have you ever wanted to try ikebana for yourself?

You don’t need any special skills or experience to begin.

Even if you’re just a little curious—or simply looking for a new, mindful hobby—ikebana is an art that anyone can enjoy.

Here’s a simple guide to help you start your own ikebana journey.

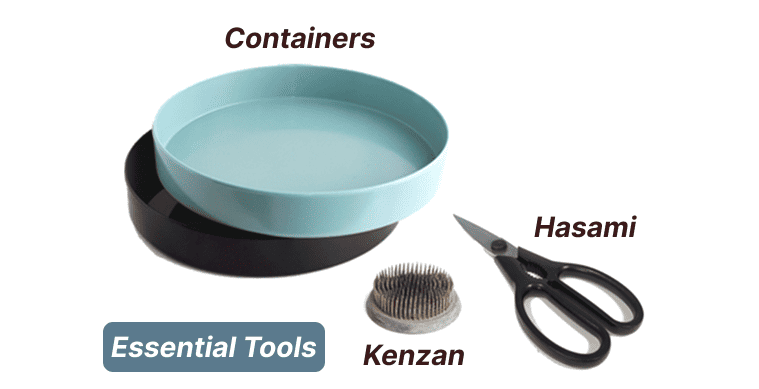

Essential Tools

To begin ikebana, you’ll need a few basic tools.

Here’s a quick overview of what you’ll use and what each item is for.

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Kenzan (剣山) | A metal needle-point holder that keeps stems firmly in place. |

| Hasami (鋏) | Sharp Japanese scissors for making precise, clean cuts. |

| Containers | Tall vases (nageire) or shallow dishes (moribana), depending on your chosen style. |

Optional tools such as pin frogs, water basins (suiban), or fixing wires may also be used—depending on the school or arrangement style.

How to Begin

Once you’ve prepared your tools, it’s time to start arranging.

Here are a few simple steps to guide you through your first ikebana experience.

- Select seasonal materials — flowers, branches, or leaves that reflect the current season.

- Use the three-line structure — Heaven (shin), Human (soe), and Earth (hikae) to create balance.

- Focus on space and flow — the empty areas (ma) are just as meaningful as the flowers themselves.

- Work in silence — breathe, move slowly, and enjoy the meditative rhythm of arranging.

Each stem you place becomes part of a quiet story between you and nature.

Learn Online or In Person

Not sure if written steps alone are enough to understand?

That’s okay—seeing ikebana in action makes all the difference.

Why not try a hands-on lesson or workshop where you can learn directly from an ikebana instructor?

Whether you’re in Japan, abroad, or joining online, here are some easy and welcoming ways to experience ikebana for yourself.

Yumehana Ikebana (Kyoto)

Offers private and group lessons in Kyoto, as well as online classes in English for international learners.

Whether you’re visiting Japan or joining from abroad, you can experience ikebana’s elegance firsthand.

Sakura Experience Kyoto

Provides short-term workshops taught in English—perfect for travelers who want a hands-on cultural experience.

Lessons include seasonal flowers, traditional tools, and creating your own ikebana arrangement to take home.

Through these programs, even beginners can enjoy ikebana with confidence.

If you’re curious, take this opportunity to experience the joy of ikebana and connect with one of Japan’s most beautiful traditions.

Watch and Learn on YouTube

If taking a class or joining a workshop feels a bit too formal, learning through YouTube videos is another great option.

The YouTube channel Ikebana Master offers beautifully filmed lessons with English subtitles, making it perfect for international viewers.

From traditional arrangements to creative modern styles, each video walks you step by step through the art of ikebana—so you can enjoy learning at your own pace, wherever you are.

A small break — a little side note

Feeling inspired to try ikebana yourself? This clear and friendly video explains the basics of Japanese flower arrangement in simple English, perfect for beginners.

It also covers key ikebana terms and their meanings, helping you learn step by step at your own pace. With its easy guidance, you can start enjoying the art of ikebana right from your home!

Finding Your Own Way

There is no single “right” way to learn ikebana—the most important thing is to enjoy the process.

Now that you’ve discovered its history, philosophy, and quiet beauty, you may find yourself appreciating ikebana even more deeply.

Through this gentle art, your inner calm and dialogue with nature can blossom into something truly beautiful.

Conclusion: A Quiet Art That Speaks to the Soul

Ikebana is more than the art of arranging flowers beautifully.

It is a way of capturing the present moment—its space, time, and season—through the quiet language of nature.

Every stem, every angle, and every shade of color teaches us to see beauty as it truly is, and to notice it with gentle awareness.

To practice ikebana is to engage in a silent dialogue with nature—and, in that stillness, to meet yourself anew.

Communication does not exist in words alone.

In ikebana, silence, space, and reflection become forms of expression.

The beauty of ikebana does not shout—it whispers.

And within that whisper, we rediscover something eternal, something deeply human.

Perhaps all it takes to begin… is just one single flower.